7 Questions For Photographer Dena Eber

JWA talks to Dena Eber about her passion for photography and her new book You Refuse to Believe That You Ever Liked Pink.

JWA: You’ve been a visual artist and professor of digital arts for many years. Where did that journey begin for you, and where do you hope it will go?

Dena Eber: My art journey started in the 1970s, when my dad gave me his 35 mm Yashica camera, which in those days was only film. I enrolled in a darkroom class at the community arts center, and I “caught the bug” and have been making art since. I was a math and computer science major in college, but I got a minor in photography, which was my true passion. When I was in graduate school for computer science, I had a tuition waiver, so I proceeded to enroll in all the photography and art classes that my time would allow. Clearly, art and photography were all I ever wanted to do.

After writing code for the Environmental Protection Agency for a few years, I left and enrolled in an MFA program at the University of Georgia in Athens, where I was living at the time (1991). Coincidentally, the School of Art obtained a lab of Mac computers, and given my computer background, my assistantship was to help figure out how to make art with these machines and eventually teach classes in what we then called “computer art.” My photography practice moved from the darkroom to the computer, and I have worked with digital tools ever since. My PhD work was exploring the creative process around constructing virtual reality art, which was also pretty new in the '90s.

This is how I ended up in digital arts, which I still practice, but I am, and always have been, a photographer. Academia has finally caught up, and I now teach in both photography and digital arts.

I hope this journey continues until my end, as I plan to tell stories with my camera for the rest of my life. This is something I am simply driven to do, much like breathing and eating. As I reflect, I see that much of my art is connected to my community and Jewish traditions. My hope is that people will be interested in experiencing my work however I get it out there, be it on Instagram or a website, book, museum, or gallery.

JWA: What do you find compelling about photography, particularly in contrast to artistic mediums?

DE: I'm not 100% sure why I am so passionate about photography—maybe because my father gave me my first art tool (a camera), and I never gave it up. I don’t feel that photography is a lot different from other art media. I know many people respond to photographs as if they represent a singular truth, having captured a real moment that happened. I don’t buy that, and I feel that a photograph represents one of many truths, mostly from the perspective of the artist. Much like a painter, printmaker, or sculptor works, the photographer makes whatever reality they want to reveal, and this holds for documentary photography. From simple things like what is in the frame and what is not, to camera movement, lighting, darkroom tricks, and digital post-processing, a photographer can make an image look how they want, even before digital tools and AI.

My camera feels like an extension of me, and even my soul. When I work, I don’t think—I just make as if my camera is a limb and an extra set of eyes that knows what to do. This is what I find most compelling about photography.

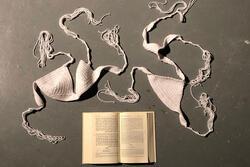

JWA: Tell us a bit about your latest project, a photo book titled You Refuse to Believe That You Ever Liked Pink.

DE: You Refuse to Believe That You Ever Liked Pink is a project that I created with my child, and it is about how we both transitioned; Margaret became Alex, a nonbinary identity, and I became the mother of Alex, accepting that I no longer had a daughter. The project is about our transitions, but also about our relationship and the unconditional love that we have for each other.

The project unfolded over a year, the period that I feel coincides with the initial mourning process, first experiencing loss and slowly moving to acceptance and then eventual peace. The project is about this first phase.

JWA: What do you hope the effect of publishing this photo book will be?

DE: When I first started the project, my hope was to tell our story, so other mothers, parents, and loved ones connected to people who transitioned could identify and seek comfort. I have had students who have transitioned, and I watched their parents cut ties with them, or otherwise question themselves or their child. However, I found that people who are transitioning and people who are on the periphery of this process understand their own world a little bit more after experiencing my book. Even parents who embrace their child’s transition could use a community. One person who was transitioning to nonbinary cried as they read an early version of the book. They said that they saw themselves and their mother in it, and they wanted to share it with their mother.

In short, I hope telling this story helps people, and works towards repairing the world (tikkun olam), even in a tiny way.

JWA: Is there a photo in the collection that is your favorite or is particularly meaningful to you? Can you walk us through what this photo means to you as both a mother and an artist?

DE: This is a hard question, because so many of the photographs expose aspects of our transitions and our relationship that are important. However, I think the one I keep going back to is of Alex holding daisies and laying in the flowers. Alex was wearing one of the first men’s shirts that I bought for them and was also sporting a new haircut that they felt reflected a nonbinary gender. In the picture we see flowers and a strong Alex embracing them, which shows that both flowers and Alex can be genderless. The colors are warm, indicating a sunset, but the warmth and the flowers hint at the start of something great on the cusp of an ending. The sum total of this photograph is Alex as Alex and me seeing them as Alex. The future is waiting in this picture, and it expresses hope for both of us.

JWA: In an interview with Huck magazine, you mention “sitting shiva” and “saying kaddish” [the mourner's prayer] for Alex’s past identity. Were there other ways in which your Jewish values guided you through this process?

DE: The other ways in which my Jewish values guided me in the project are embedded in almost every choice I made and every photograph that I shot. One of the things that I love most about Judaism is that it is an evolving religion; for some it moves very slowly, for others it is whiplash fast, and for some it moves more closely with the times in relation to halachic law, which is where I see myself. When I was growing up, women could not be rabbis, but now it's common to find female rabbis in Conservative and Reform synagogues. When I was a child, my family belonged to a Reconstructionist shul in Philadelphia, and my favorite part of my Jewish education was the Sunday classes I had with Rabbi Kaplan (not THE Rabbi [Mordecai] Kaplan) post-confirmation. He asked us to pre-read the Torah portion of the week and come in prepared to talk about what we thought it meant against the backdrop of modern times. We hit many of the contemporary notes in that class, from feminism and abortion to war and sexual orientation. We didn’t touch on gender identity, but a discussion would square nicely with the trajectory of the progressive nature of our readings and discussions.

My guess is that if we were to discuss transgender issues today, we would talk about how people should be their true selves and that in doing so, they would move closer to god. (We were allowed to write god out fully, and we didn’t have to capitalize the “g.” There was a lesson in that, too.)

I reflected on god a lot during this process too. As you know, if you put ten Jews in a room and ask them about god, you will get twelve answers—maybe thirteen or fourteen on a good day. We were taught, and I believe, that god is so big and vast that god is genderless, neither male nor female, but also both and more. While god has a feminine divine presence, like Shekhinah, I see god as genderless. Perhaps being a genderless human reflects god in a closer way. I don’t know, but I have chosen to map this idea onto my beautiful child.

I lost my mother at the same time that Margaret became Alex. As I sat shiva for my mother, I realized I was sitting shiva for Margaret, too, losing a mother and a daughter at the same time. I was mourning both my mom and Margaret, but I was also mourning my old identity as a daughter and as a mother of a daughter. I find the Jewish traditions surrounding death to be not only comforting, but exactly what one needs to get through a period like this. It gave me space to accept the death, but then to move forward. In the case of Alex, it allowed me to fall in love with who Alex was becoming and it gave me space to be the mom of a nonbinary young adult.

My Jewish values allowed me to love my child unconditionally as they became who they were meant to be, a person who I believe is even closer to god.

JWA: What advice do you have for parents whose child has recently come out as transgender?

DE: First, don’t forget that they are still your child no matter what, and focus on the special love that only a parent and child can share. Not all parents will feel loss, but I did, and many will. If they feel this way, then know that it is normal and OK. Many transgender folks refer to their old name as their "dead name," so it's fitting to mourn the loss of who you thought your child was, but then fall in love with the person they're becoming. The transgender person is becoming their truer self, and that will hopefully make them happy. Keep your child’s happiness in mind as you navigate whatever you're going through and think about the amazing new person you will now have in your life.