An Interview with Elaine Weiss, Author of "The Woman’s Hour"

JWA sat down with author Elaine Weiss to discuss The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote, one of JWA’s 2019-2020 Book Club picks. Weiss’s latest book chronicles the struggle for women’s suffrage in the United States, introducing readers to the women and men who tirelessly fought for the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment.

This interview is part of JWA’s 2020 Suffrage Series on the blog.

Both your books, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War and The Woman’s Hour, explore the lives of American women in the late 1910s. What sparked your interest in the women of this era?

It's a turbulent and fascinating era in American history, the transition from the nineteenth to twentieth centuries, and the two books are connected in certain ways: The extraordinary World War I work of women—especially by those who supported women’s suffrage, as many in the Land Army did—was used as a potent argument that women deserved the vote. They had proven their citizenship, their patriotism, their bravery. It became much harder for Congress to ignore the federal suffrage amendment, which had been stranded in Congress for 40 years. It is no coincidence that the Amendment finally got passed just months after the end of WWI. Some of the same women I wrote about in Fruits of VIctory turn up in The Woman's Hour.

The Woman’s Hour is filled with courageous, vivid, complex characters on all sides of the suffrage question. As you were researching, who surprised you the most? Who do you wish more Americans knew about?

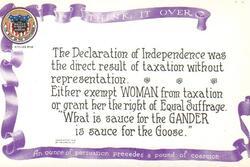

What surprised me the most was that there were organized groups of women who opposed women obtaining the right to vote. They were called the "Antis," and they used a variety of arguments to make their case: That women demanding political equality with men would upset traditional gender roles, not only in the public sphere, but in private life, too. They warned that men might have to take care of the babies if women left the home for an hour to vote; or women might abandon their families completely if allowed to have such independence. They also contended that women’s suffrage portended a whole range of changes—to the family and to society—that were unhealthy. We still hear those kinds of arguments today against the Equal Rights Amendment, which was intended as the next step to secure women's rights after suffrage: It was introduced into Congress in 1923, and it is still not enacted. Antis who were religiously devout also believed women's equality went against God's Plan—and we know we still hear that argument! I think it's important to explore the rationales of the Antis, because we're still contending with those mindsets and arguments today.

We don’t see many Jews in the story of the Tennessee ratification. Were Jewish women involved in the suffrage fight? How were they greeted by their Christian counterparts? What positions did religious and community leaders take on suffrage?

Jewish women are certainly involved in the American suffrage movement—it spanned over seven decades and three generations. A very early advocate of woman suffrage, in the mid-nineteenth century was a Polish Jewish immigrant named Ernestine Rose, who was a collaborator of Susan B. Anthony’s. Jewish women were involved in the movement in any city where there was a significant Jewish population. Jewish women involved in labor organizing also worked for the vote. In the story I tell about Tennessee as the last state to ratify, one of the women I follow is Anita Pollitzer, a young Jewish woman from Charleston, who joined the more radical wing of the movement and was very busy lobbying in Nashville. I found Jewish women on both sides of the issue in Tennessee. There were also Jewish anti-suffragists, including Annie Nathan Meyer, who founded Barnard College in New York City. She believed in women's educational rights, but did not think they should vote. Her sister, Maud Nathan, was a prominent suffragist. (Imagine seders!)

There was also an ongoing feud between two prominent rabbis over suffrage: Rabbi Stephen Wise was a staunch advocate of women’s suffrage, and he made speeches supporting it all around the country. He even cut a vinyl record of one of his pro-suffrage speeches, which was distributed. (This was all before radio, so records were the only way to distribute "audio.") His nemesis was Rabbi Joseph Silverman of Temple Emanu-El in New York City, who was against women voting. They dueled from the bima on the subject for years.

The final chapter of your book describes the fraud, harassment, and violence that Black women who attempted to vote faced. Many readers are familiar with the repression of Black women’s and men’s votes in the Jim Crow South. But I was struck by the anecdote you included about the misleading, threatening flyer distributed to Black women in Boston on election day 1920. How free were Black, Native, Asian, and Latina women to vote in the North and West?

The Nineteenth Amendment promised the vote to every woman citizen of eligible age, in every state, in every election. However, there were state and local statutes and policies—Jim Crow laws—which would rob the vote from Black women in the southern states, just as black men, guaranteed the right to vote by the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, had been deprived of their right to vote by poll taxes, ridiculous literacy tests (recite the state constitution), intimidation (losing your job), and violence, including lynchings. Congress actually held the power to curb these state infringements of voting rights, but chose not to. Black women and men would not be able to freely exercise their voting rights in the South until the Voting Rights Act of 1965, though Black women had been very active in the suffrage movement. But all that is not the fault of the Nineteenth Amendment; it is the fault of racist state legislatures and Congress.

Native and Asian American women were not covered by the Nineteenth Amendment, as they were not considered citizens in 1920. Native Americans won citizenship rights in 1924, but again, many states placed obstacles to voting; Native women and men weren't able to freely vote in many states until the mid 1950s. Asian American women, as well as men, did not achieve full voting rights until the mid-1940s, after WWII.

The Woman’s Hour portrays long-term struggle and short-term urgency, as well as a combination of direct action and politically savvy insider negotiating to win enough votes to secure the passage and ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. What can the struggle for suffrage teach today’s activists?

I think the struggle for women’s suffrage holds important lessons for activists today, the first being: Persistence is key. These women were defeated, betrayed, and disappointed so many times in the seven decades of the movement—which spanned over 900 state, local, and federal campaigns. But they always picked themselves up, learned from the loss, adopted more effective techniques, and enlarged the movement. They had to change hearts and minds—attitudes about women's roles and rights in society—and then they had to master the intricacies of political persuasion and political power. That's what a long-term movement has to do. They learned to use "sensational" protest tactics—voting "illegally," withholding their taxes, picketing the White House, burning the President’s effigy—and went to jail as a result. But the suffragists didn't just protest: They also drafted legislation, campaigned door to door, became skilled lobbyists in Congress and statehouses. So, the lesson is: Protest is patriotic, and important, but it must be followed up by sustained political strategies. It's not enough to sign a petition on Facebook or show up at a march. It's what happens the next day that is the test of a movement for change.

Would Ms Weiss do a Zoom evening for the Quarantine Book Club?

Interesting. I will read this. I did a Masters Thesis on this very topic.