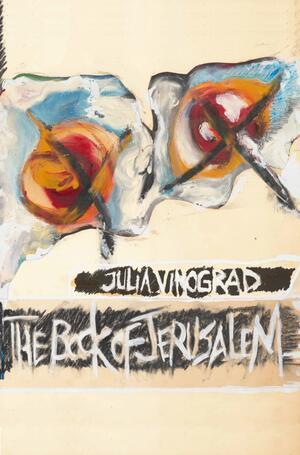

"The Book of Jerusalem" by Julia Vinograd

Via Zeitgeist Press.

For the last 50 years, Julia Vinograd could be found on the streets of Berkeley, California, dressed in black robes. Every finger bore a ring from which a plastic eyeball stared back at you. Her floppy beret had a button that announced “Weird and Proud.” Often as not, she was blowing soap bubbles. She was always hawking her latest chapbook of poems, portraying the street people and bohemians of Berkeley with the artistic skill of R. Crumb—and with a lot more warmth and humor.

Tourist attraction and eccentric she certainly was, but she was also a poet of the first order. When she died of cancer in 2023, a documentary about her was already in production, and her publisher, Zeitgeist Press, was bringing out her masterpiece, The Book of Jerusalem, a series of poems describing the dysfunctional relationship between God and his holy city.

The marital squabbles between God and Jerusalem have been good copy for a long, long time. From Isaiah (eighth century BCE) to Malachi (fifth century BCE), the poetic project of the Hebrew prophets centered on slut-shaming Jerusalem, personified as God’s unfaithful wife, who “went whoring after strange gods.” Vinograd offers a wryly feminist revision of this tradition. Not since Shakespeare’s Cleopatra have we seen so thoroughgoing a femme fatale.

Vinograd’s book is also a painfully relevant study of religious violence, of which Jerusalem has so often been the epicenter. She exploits to the fullest the irony of men playing at war and children suffering for it. She takes no political sides: her cause is that of humanity. Both Zionists and anti-Zionists will be disappointed if they come to this book looking for ammunition.

In the later poems, there’s a dreamy Chagall-like nostalgia for the world of Jewish childhood, as in this Sabbath memory from the poem “Jerusalem’s Book of Fairytales,”

The smell of bread coming out of the oven

filled the house like prayer.

Outside children played marbles and jump rope

swimming in safety.

Their voices rose like birds that know no borders

flying in and out of God’s beard while He slept.

There’s a strange disparity between the character Jerusalem, who is clearly drawn from life—and with autobiographical authority—and Vinograd herself. She lived alone, never had a lover, never used drugs or drank. So, how did she create the powerful Jerusalem character, whose full-blooded realism and feminist chutzpah make Ibsen’s heroines seem anemic?

The mystery of The Book of Jerusalem may perhaps be solved by the biographical facts. Vinograd had epilepsy, a condition that ultimately earned her a disability income. Also, as a child she suffered from polio, which left her with a lifelong legbrace and a limp. As a disabled child, she turned to books as a substitute for the active outdoor life disease denied her.

When her health and mobility improved, she attended an all-girls high school in Pasadena. The cruel social realignment all children suffer after elementary school was no doubt worsened by the special competition among girls in early adolescence. With her leg brace and her seizures, Vinograd may well have been singled out for unusually cruel treatment.

Her erotic shyness in hippie-era California, which endured throughout her life, could have stemmed from a sense that she was defective, unlovable, unwelcome in the world of intimacy. That would help us to understand why she passed the decades in Berkeley like a nun, erecting around herself an impenetrable persona, a bizarre and self-sufficient poetic identity. In the trademark motto she wore buttoned to her hat, she was “weird and proud.” But within her were all a woman’s feelings and need for love, and these ultimately erupted in The Book of Jerusalem, a grandiose fantasy of erotic confidence.

The parallels that come immediately to mind for Vinograd’s Jerusalem are Andy Warhol’s radiant silkscreen portraits of movie idols. If we bear in mind his childhood, in which he turned to movie magazines for a happier imaginary life, one in which he too lived among the stars—so unlike his real life as a sickly, picked-on kid—we can appreciate the poignant sadness of his silkscreened Marilyn’s glamor.

For parallel reasons, Julia Vinograd’s Jerusalem has the neon magic of Warhol’s best silk-screen paintings. Out of her personal suffering and poetic genius, she created an iconic image of Jerusalem that is powerful, feminist, and unforgettably, startlingly modern.