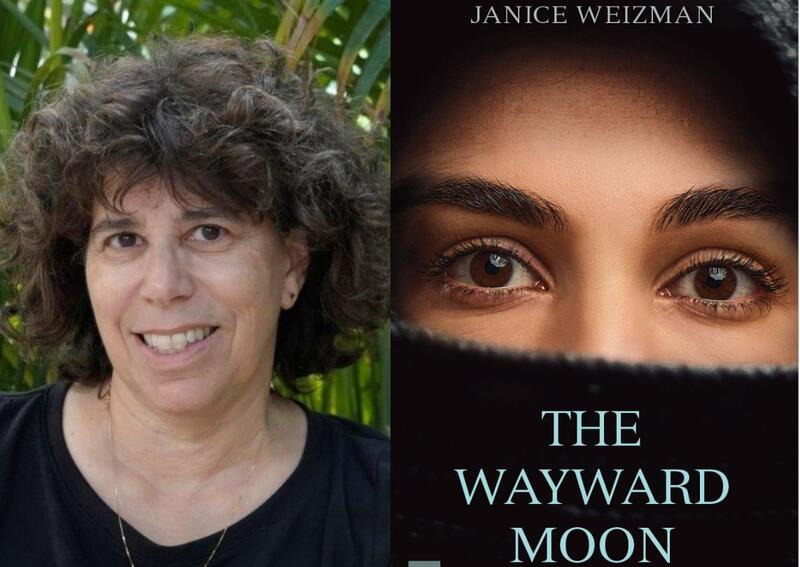

Q & A with Author Janice Weizman

A memoir writer and history lover, I gravitate toward historical fiction, especially World War II and Holocaust stories. But occasionally, I read tales from earlier times, from long-lost centuries, about characters and contexts that seem otherworldly. Only two pages into Janice Weizman’s debut novel, The Wayward Moon, I was hooked. The novel tells the story of Rahel, a Jewess in 850 AD, who loses everything—parent, home, community, identity—in a flash. Her voice is full of wonder and confidence, naïvete and knowing. The Middle Eastern setting—the region where Janice and I both live—is rich with description and sensory details.

While I’ve never experienced a life-or-death situation like Rahel, I related to her curiosity to learn, her need to think quickly, her desire to make smart decisions, her yen to stay alive. Throughout her story, the stakes are high, which, unfortunately, reminds me of what Janice and I are dealing with in our everyday lives in Israel.

Originally published in 2012, the prize-winning novel has been re-issued with a preface by the author, explaining why Rahel’s story of survival is timelier now than ever.

Jennifer Lang: The Wayward Moon is set in the ninth-century Middle East. What was the impetus—the nugget of story or gnawing of fact that led you to write it?

Janice Weizman: The idea for the story came to me many years ago, when I took a course on the history of Islam. What struck me most was the absence of women. While we read from many primary sources written by and about men, there was nothing written by or about women; if women did appear, it was with regard to whatever was relevant to the writer. This was true not only for Islamic works, but also for Jewish and Christian writings.

I found their absence baffling and disturbing. I understood that, for most of human history, women’s lives were constrained and controlled by communal and familial expectations. But what if a woman suddenly found herself with no family, no community? What if she were freed of those ties? I began to imagine the story of a young woman who, on the eve of her wedding engagement, is forced by circumstance to flee her village and disguise herself as a boy. As a naïve teenager with no experience of the world, how would she survive? What would be her plan of action? How would she know who to trust? And what would happen to her if she made a mistake?

JL: The setting—scenery, clothing, food, customs, professions—is so vivid and rich from start to finish, and yet, it is the ninth century. How long did you spend on research? What most helped you during that process?

JW: One thing I admire about Islamic history is the spirit of the region that infuses it. The Middle East is rich with color, energy, emotion, dramatic geography, music, art, architecture, warm weather, and food. I wanted to incorporate all of that into my story about this time. Living in Israel very much informed that. The fact that I’ve travelled in Egypt, Turkey, and Morocco, and India also helped; in each of these places, it wasn’t hard to find palaces, mosques, traditional schools, travellers' inns, and local markets brimming with sights, smells, and sounds. These locations gave me an idea of what it looked like 1,200 years ago.

Since most available information about the time was academic, I searched elsewhere. For ideas about how people dressed, I looked at Persian and Middle Eastern art. To better understand the dominant motifs in the culture, I looked at translations of Arabic poetry. And, most importantly, I looked at aspects of life in the Middle East that persist today: culinary traditions, song lyrics, cultural attitudes about men, women, love, family, and rivalry and power.

JL: Years ago, you taught a workshop on auto-fiction (fictionalized autobiography) for my writing students at Israel Writers Studio. Is Rahel based on you in any way? Or is she based on anyone in your life or anyone who has lived or is she wholly fictional?

JW: Rahel, and everything that happens to her, is wholly fictional. I had to imagine every aspect about her; what she looked like, how she spoke, how she’d react to the difficult situations in which she found herself. The most challenging thing was to see things through her perspective. In the first draft, she was feisty and brave, thrilled to learn to ride a horse, revelling in her newfound independence. But in later drafts, I realized that she would have been fearful and risk-avoidant and would have yearned to find a man who’d marry her and give her a home. If she was to have any reserves of resilience and strength, they’d have to be hard-won and filled with trepidation.

JL: Before he’s murdered, Rahel’s father tells her about the Greek play he’s reading, Antigone, and it becomes part of her quest to understand its message. Why Antigone? What does it mean to you?

JW: The Wayward Moon is set in the Golden Age of Islam (roughly 750 to 1300 AD). The growth and success of the culture gave it the confidence to learn from the cultures that preceded it, like the Greek writings, which became available through translations into Arabic by Christian monks. As a physician, Rahel’s father reads these works. Before his murder, he tells Rahel about the Greek tragedy Antigone and how the heroine relies on instinct and intellect to guide her. After his death, when Rahel has lost everything and flees, she clings to these words as a treasured piece of advice, and the quest to know more about the story becomes a connection with her father.

I chose to put Antigone in the novel because I’m intrigued by the idea of one culture influencing another. But more importantly, because the period I wrote about is one in which women had been rendered completely passive, I liked the idea that when Rahel is in disguise and alone, she comes across this strong and proactive female role model who becomes her inspiration.

JL: There are so many different parts of the story that resonated with me, but perhaps what most struck me was Rahel’s decision to follow her heart, something I did when I was around the same age as her. Have you, too, followed yours? If so, can you describe the situation and where it led you?

JW: As a 19-year-old high school graduate in Canada, I came to Israel for a one-year program through Hebrew University. Raised in a Zionist home, I fell in love with the country and decided to try to start my adult life here. It was a little like a love affair—ecstatic, illogical, emotional. But it’s been over 40 years and I’m still here, and I’m very happy with how things turned out, so I guess you could say that the relationship was worth it :).

JL: The Wayward Moon deals with communities of Jews living in Arab lands. Do you have any connections to those communities? And if not, did you worry that you might be accused of “cultural appropriation?”

JW: My roots are entirely Eastern European Ashkenazi, and until I married my Moroccan-born husband, I had zero connection to Sephardi communities. The question crossed my mind many times, and after the book came out, I started wondering why I’d chosen this time and place, rather than writing about a community that was more familiar.

Growing up, I recognized that I’d been reluctant to delve into the story of my own community, my ancestors, who’d immigrated to Canada and the US around the turn of the century after fleeing the little shtetls of Belarus and the Ukraine, who had no interest in looking back. They never spoke about the places they came from, and ultimately, that information was lost. A gap developed between my generation and that of my great-grandparents. This sense of dislocation, of lost history and a need to reconnect with my cultural roots, became the theme of my next novel, Our Little Histories, which came out last year. So I guess you can say that writing has brought me full circle.