Bringing the Borscht Belt Back to Life

JWA talks to Marisa Scheinfeld, founder and director of the Borscht Belt Historical Marker Project.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

JWA: Before you talk about the project, can you briefly explain what the Borscht Belt is and why it's important in Jewish American history?

Marisa Scheinfeld: From the 1920s through the mid-1960s, the Borscht Belt was one of America’s top vacation destinations. The area was about 90 miles from New York City and was primarily known as a summer retreat that provided culture, entertainment, and leisure for predominantly East Coast American Jews. The antisemitism that flared nationally in the 1920s was the push that helped to create over 500 resorts, 50,000 bungalows, and 1,000 rooming houses. For more than 45 years, the Borscht Belt created a feeling of belonging for working and vacationing Jews, in a world where they’d experienced so much prejudice.

The region also had a strong influence on the cultural and economic landscape of New York State and shaped popular American culture and imagination. Before Las Vegas became world renowned for its entertainment, the Borscht Belt was the country’s premier entertainment destination. Stand-up comedy originated in the theaters of Borscht Belt resorts.Those who visited the hotels and bungalow colonies year after year forged social connections and cultural bonds, many of which have lasted to the present day. Those employed by the vacation industry were able to pay their bills and finance a greater life for themselves and their children. For those who lived year-round in the region, they welcomed the economic and cultural boom and embraced the lively activity that brought a touch of the cosmopolitan to “the country.”

When spoken about in retrospect, the Borscht Belt often assumes a very male-centric lens. But the area’s hotel industry, in many ways, was built on the backs of Jewish women. One of the most notable was Jennie Grossinger, the daughter of Austro-Hungarian immigrants Malka and Selig Grossinger. Malka and Selig bought farmland in Liberty, NY, which eventually morphed into the iconic Grossinger’s Hotel and was primarily run by Jennie. As a female in a male-dominated world, working in a family business that bore her name, Jennie Grossinger was unique in how effortlessly she combined old-world traditions and modern American style with a savvy sense of commercial marketing. She hired publicists to implant the Grossinger name into the public realm and intrinsically knew to put herself forward as the face of the resort. In doing so, she branded herself and Grossinger’s as a renowned establishment, making her a pioneer in the field. Jennie was one of the most prominent female figures of the Borscht Belt hotel industry, but there were many others.

Women were also important in Borscht Belt entertainment. While the presence of women was at first a rare thing in Borscht Belt hotels, female Yiddish theater performers Molly Picon and Fanny Brice had an early presence in the region. Female singers like the Barry Sisters and Marilyn Michaels performed regularly in the Borscht Belt and comedians such as Phyllis Diller, Estelle Getty, Totie Fields, Laine Kazan and Joan Rivers established their careers in its many theaters and showrooms. There was also Jean Carroll, who was apparently the inspiration, or part of the inspiration, for Mrs. Maisel. Many of these women discussed sex, gender, and religion in their acts during a time when women were seen and not heard. I’ve also read that Bette Midler was a singing waitress at the Brickman Hotel in Fallsburg along with Kathy Bates, another singing waitress who worked at a restaurant in Monticello—all before both rose to immense levels of fame.

JWA: Why did the Borscht Belt decline in the 1980s and 1990s?

MS: The Borscht Belt began to decline starting around 1965, but saw the deepest dive from the 1970s through the 1990s, when the remaining hotels closed its doors (except for Kutsher’s, which closed in 2013). The decline was due to a variety of factors: the growth and proliferation of the suburbs, the rise of inexpensive airfare, the burgeoning cruise industry, and generational changes. Its demise can also be attributed to the events of the 1960s, a decade that saw the civil rights, women’s liberation and gay rights movements, along with a war in Vietnam. Many long-standing ideas shifted during this time, and for the groups mentioned, the mid-1960s brought fewer restrictions. Jews and minorities who’d experienced many closed doors in America saw a lot of those doors open. Also, the Catskills didn’t keep up with the changing times— the food was the same, the amenities the same, the entertainment the same, making the staple pastimes of the Catskills less appealing to younger generations. All combined to create a “perfect storm” of factors that made the Borscht Belt less enticing.

JWA: What are the main goals of the Borscht Belt Historical Marker Project?

MS: The mission of The Borscht Belt Historical Marker Project is to interpret and designate places important to the Borscht Belt’s vibrant history and to consider its impact on American Jewish life, the legacy of the Catskills, New York State history, and American culture and entertainment. At our core, we’re a historic preservation group whose goal is to celebrate this immensely cherished and important era. But we are, and intend to be, much more.

As of our inception in August of 2022, there are no historical markers dedicated to the Borscht Belt era in either Sullivan or Ulster County [New York]. This large-scale interpretive marker system will be easily accessible to the public, benefit the communities they’re placed in by sparking interest in local history, and educate residents and visitors about the events that have shaped the region’s past. Our goal is to create a comprehensive marker system and self-guided audio driving tour that traverses the landscape formerly known as the Borscht Belt, along with rolling out an array of public programming and educational materials.

JWA: Why is it important to you to teach people about and preserve the history of the Borscht Belt?

MS: Between the reasons why the Borscht Belt was created (antisemitism) and its impact on American Jewish culture and history and the region at large, including its crossover into mainstream American popular culture, the era is truly legendary. The passing of the people once part of the era, along with the deterioration and disappearance of its physical spaces, signal an entire culture and momentous history that is departing. The era’s profound impact is a topic that deserves to be preserved, in all ways possible. The mission of the Borscht Belt Historical Marker Project is to be a conduit for people to discover the Borscht Belt’s vibrant past, particularly as the region is experiencing a renaissance. Looking back, in this sense, seems just as important as looking ahead.

JWA: You also have a personal connection to the Borscht Belt. Can you talk about that?

MS: My fascination with the Borscht Belt is not just about its place in American history or its role in Jewish American life; it was and has always been personal. My father’s parents met while my grandmother and her sister were hitchhiking the woodsy roads of Sullivan County one summer. They spent their summers at bungalow colonies like East Pond, Walter’s, and the Irvington Hotel. Later, my grandparents owned a condominium at Hidden Ridge, a community near Kutsher’s. My maternal grandparents went to the Nevele Grand Hotel, close to Ellenville, for their honeymoon and vacationed at two bungalow colonies in the towns of Wawarsing and Monroe for over 55 years combined. As a result, both my mother and father spent summers during their childhoods and teenage years in the Catskills. In the mid-1980s, when my father was fresh out of his medical school residency and looking for a job, two positions were available, one in Sullivan County and another in Connecticut. My father chose the job in Sullivan County because of his own attachment to the Catskills and his desire to create a whole new set of memories in the area with his own growing family.

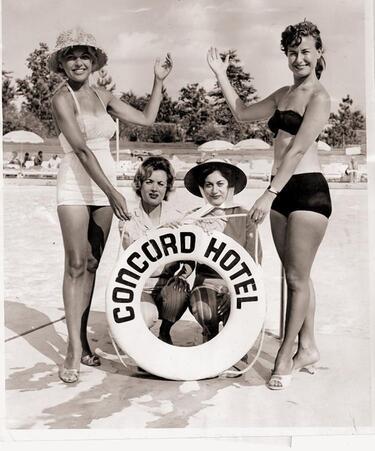

As a young child, I would visit hotels such as Kutsher’s or the Concord on weekends with my family. Although we weren’t guests at these hotels, we strolled in as if we were. At the time, Kutsher’s and the Concord experienced a mere fraction of the foot traffic they had once accommodated, but looking back, they were these fantastic places where I knew I was always going to have fun.

The Borscht Belt continued to be important to me as I grew into adolescence. One of my first jobs was as a lifeguard at the Concord’s outdoor pool the summer before it closed in 1996. For me, the Catskills is home. When I returned as an adult with a camera slung over my shoulder in 2010, I was on familiar ground. Since the publication of my book in 2016, I’ve been fortunate to be engaged in a lot of dialogue surrounding the era. With a second printing of my book in 2020, and another book in the works that includes alternate and fringe histories of the Catskills (and Hudson Valley region), and now the Marker Project, it seems I’m ever more tied to the region.

JWA: What's the timeline for this project?

MS: We dedicated our first of 20 historic markers in the town of Monticello, NY on Thursday, May 25. There will be two more dedications—including an exhibition and concert—in mid-August. Marker dedications will continue into the fall and throughout 2024. Ideally, the entire marker trail will be completed by early to mid-2025.

When complete, the permanent marker trail, combined with its audio tour and compendium programming, will encourage people to venture out into landscape and visit the various towns that comprised the era. Juxtaposed with the Catskill’s natural beauty, the Marker Project and its driving tour will include the various towns and villages where documented hotel and bungalow colonies once existed. In this sense, the project aims to be a fun, educational endeavor that encourages the experience of the physical place while also promoting economic development and tourism throughout the region.

JWA: For those who can't see the historical markers in person, how can they still learn about the project and about the history of the Borscht Belt?

MS: People can visit our website, which has a lot of information, including a page for each marker with extended stories and visual media. We’ll also have images of the markers themselves – which are dual sided and contain photographs, making them different from most historical markers – in addition to being as vibrant in color as the era itself. We’ll try to record and document as many of the events as possible. You can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, and join our mailing list.

My grandparents owned Rubel's Mansion in South Fallsburg, which became Gilbert's. My parents met at a Catskill Hotel. My father was a chef who worked in the hotels during the summer, and I was a waiter and busboy from 1960 through 1969. My novel, "He Lost it in the Catskills," has just been published. I worked at the Irvington, Pauls, the Karmel, and Spring Lake in Parksville.

This brought back my entire childhood! I used to

Go to the Swan Lake Bungelow Colony near Monticello NY-it was the best time of my life! You brought it all back with this article! Thank you!!