Five Women Artists Whose Work Brings Us Closer to the Holocaust

Every year, as Holocaust Remembrance Day approaches, I remember the commitment I made almost 20 years ago in Poland. After marching from Auschwitz to Birkenau with a young delegation representing Argentina and Uruguay, I committed to working for the continuation of the memory of the Shoah.

I was only 16 when I had the chance to visit some of the Polish towns that were home to large Jewish populations for centuries. I also visited sites where Jews were murdered by the Nazis, who were trying a to wipe a whole people—my people—from the face of the Earth. I understood that the trip was not just about remembering the horror of what had happened, but educating future generations about it.

Years later, I became a historian of Jewish art. I learned that art is a great way to study historical processes, personal experiences, and human values. Art not only illuminates other stories—it tells its own story.

In honor of Yom HaShoah, here are five Jewish women artists who bring us closer to the story of the Shoah through their work. (Some of these artists are also included Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women on JWA’s website; see their entries for more information.)

Friedl Dicker-Brandeis (1898–1944)

Friedl Dicker-Brandeis was an artist and educator born in Vienna in 1898. The young Friedl trained in arts and crafts and later joined the Weimar Bauhaus, a German art school founded after World War I and based on the idea of creating a Gesamtkunstwerk (integral work of art) by bringing different forms of fine arts and design together. The program at the Bauhaus also dealt with issues of social justice and making a better world. Friedl was involved in multiple artistic media, such as textile design, theater staging, printmaking, bookbinding, and typography.

In 1930, Friedl, together with her studio partner Franz Singer, was commissioned to furnish a Montessori kindergarten in Vienna. She became interested in art education and ran several courses for kindergarten teachers. Her aim was to encourage young children to focus on the creative process and to understand their individual emotions and experiences through art.

With the rise of Nazism, Friedl fled to her aunt's home in Prague. There she met and married Pavel Brandeis and moved to Hronov (in the modern-day Czech Republic). In December 1942, they were deported to the Terezin ghetto, where she continued painting and applied her experience as an art educator. teaching art to young children. She led workshops, designed sets and costumes for children's performances, and even curated exhibitions of their drawings—all within the confines of the ghetto. Friedl saw in art a way to help young children deal with the harsh realities of daily life in the ghetto. She invited them to use their imaginations and create as a way of repairing their inner worlds.

On October 6, 1944, Friedl was deported to Auschwitz and gassed. After her death, drawings made by children in her classes, as well as her own sketches, were found in Prague. They are now housed in the collections of the Jewish Museum in Prague and the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles. But her legacy is much greater than these collections. Friedl Dicker-Brandeis was a fighter, not with guns, but with psychological resistance.

Charlotte Salomon (1917-1943)

When the Nazis rose to power, Charlotte Salomon was a young girl, growing up in Berlin in a middle-class, acculturated Jewish family. Her father and stepmother lost their jobs because of the Nuremberg Laws, which forbade Jews from working in many professions. Nevertheless, the family continued to live their lives in Berlin until 1938.

Salomon had been admitted to the state art academy in Berlin in 1936. It is likely that in art school, she was given guidelines for what was considered "Great German Art”—generally, work done in a classical or romantic realist style favored by the Nazis, as well as art that emphasized the values of racial purity, militarism, and obedience. Modern and avant-garde art, by contrast, were considered “degenerate”.

In 1938, Charlotte's father, Albert, was imprisoned during the pogrom of Kristallnacht, and she was sent to her grandparents' home in France. There, living under the Vichy government, which collaborated with the Nazis, Charlotte was sent to a concentration camp together with other German Jews. She was released in 1940 and met her husband, also German.

In 1941, Charlotte Salomon began to work on Life? or Theater?, a semi-autobiographical artist’s book with more than 700 painted scenes, about a Berlinese Jewish family. The first part is devoted to childhood. In the second part of the painted opera, she depicted the most significant events of the 1930s, with masses of German people portrayed as “mini-Hitlers” carrying flags with swastikas.

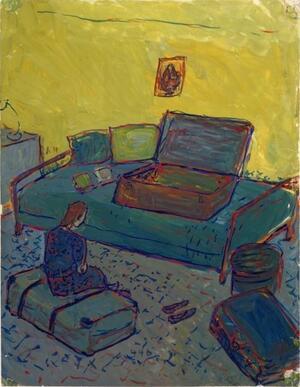

Charlotte was the first in her family to leave Germany, and her work reflects a sense of solitude and isolation. In one scene in Life? or Theater?, she is sitting alone in a room with an empty suitcase, a scene that expresses that leaving was not an easy decision.

In 1943, Charlotte Salomon was imprisoned once again, this time in Auschwitz, where she was murdered.She was pregnant at the time.Charlotte’s parents had survived the war by hiding in Holland. They found her work and donated it to the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam.

Portrait of a Woman with Two Yellow Stars by Esther Lurie, c.1941-1943. (via invaluable.com)

Esther Lurie (1913-1998)

Esther Lurie was born in Liepāja, Latvia. She studied theater set design and fine art from a young age. In 1934, she emigrated to Palestine and continued her career as an artist in the emerging Jewish state, then returned to Europe in 1939 to continue her studies.

In June 1941, with the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Lurie was arrested in Kovno, Lithuania while visiting her sister and deported to the Kovno ghetto. Under Nazi orders, Lurie painted landscapes and portraits. In the fall of 1942, at the request of the Jewish leadership of the ghetto, Esther, together with other artists, began documenting life in the ghetto. Drawing supplies were hard to acquire; artists had to smuggle them from the workshops controlled by the Nazis. In Portrait of a Young Woman with Two Yellow Stars, the yellow badge is depicted as a hole that goes through the young woman, left by a gunshot wound when the bullet passes through her body.

Esther continued drawing until the summer of 1944, when the ghetto was liquidated. She was deported to the Stutthof concentration camp in Germany, and later, to the Leibitsch camp, where she performed forced labor. Her drawings from the ghetto were hidden in ceramic vases and recovered after the liberation. Esther Lurie survived the war, moved to Italy, and eventually returned to Israel.

Esther Lurie was an artist who sought to document the atrocities of the Holocaust and leave a testimony of the Jewish experience in the Kovno ghetto. The clandestine production and documentation of ghetto life was the artist's way of struggling against murder and destruction, an act of spiritual resistance.

Gertrudis Chale by Grete Stern, 1945 (via moma.org).

Grete Stern (1904-1999)

Grete Stern was born in 1904 to a Jewish, acculturated family in Cologne, Germany. She studied drawing and typography at the School of Applied Arts in Stuttgart and worked in her hometown as an advertising designer. In 1927, she settled in Berlin, the intellectual and political capital of the Weimar Republic, to learn photography. Soon after, she opened an advertising photography studio with Ellen Auerbach. She continued her training in the Berlin Bauhaus school of art from 1932 until it was closed by the Nazis in 1933.

Unlike the artists already mentioned, Grete did not document the Shoah in her work, as she was not imprisoned in a ghetto or a camp. She fled Germany just in time, escaping to London in 1934, where she married Horacio Coppola, an Argentine photographer she had met at the Bauhaus. Her forced emigration initiated the definitive rupture with her homeland, to which she only returned occasionally after the war. The couple moved to Buenos Aires in 1935, and Grete introduced modern photography to the South American city.

Although Grete was able to leave Germany before the war, the works she produced afterward reveal another aspect of art related to the Shoah. Upon her arrival in Buenos Aires in the summer of 1935, the Jewish photographer befriended intellectuals, many of whom, like Clement Moreau, Gertrudis Chale and Gyula Kosice, fled Europe with the rise of the Nazis. They became the first subjects for her portraits. These photographs focus mostly on her sitters’ faces, which were never retouched or edited. She used different tools to create stark backgrounds and dramatic lighting. Despite their rigid poses, Grete’s subjects somehow still look natural, leading the Argentine writer Maria Elena Walsh to call these photographs “facial nudes.”

Grete also produced a series of surrealist photomontages for the women's magazine Idilio, illustrating the interpretation of readers' dreams. In the 1960s, she traveled throughout Argentina, documenting the daily lives of the native people in the northeast of the country, capturing their modest lifestyles and struggles for better working and living conditions.

Grete Stern never explicitly depicted her experience as a Jewish German refugee in her work. Nevertheless, through her focus on marginalized groups, her photography reflects her interest in social justice.

Mirta Kupferminc (b. 1955)

Mirta Kupferminc is also an Argentinian artist. In her case, she was born there, in Buenos Aires, a decade after the Shoah. As the daughter of Auschwitz survivors, she engages with the themes of memory, migration, and witnessing in her art.

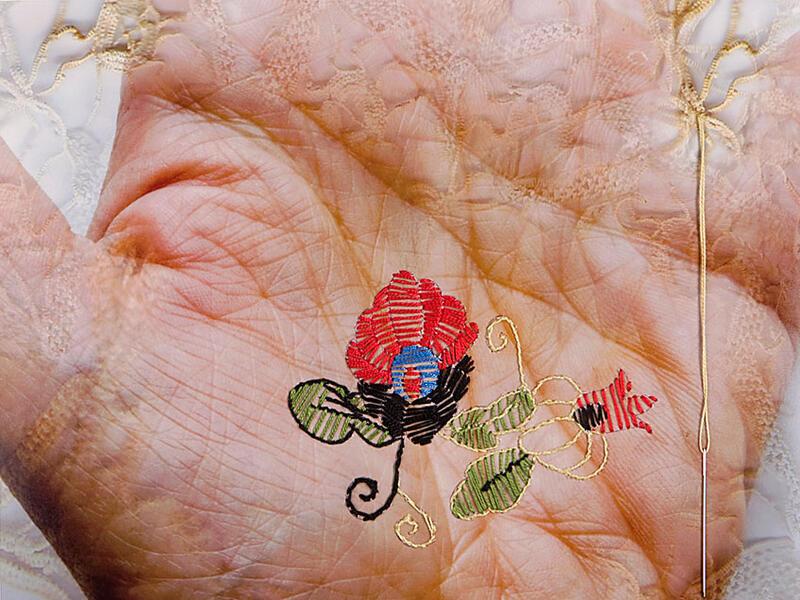

In The Skin of Memory, a performance work, she contrasts the tattooed number on an Auschwitz survivor's arm with an ornamental tattoo. In other works, like Embroidered on the Skin of Memory, she uses embroidery done in a Hungarian style, which connects to her mother's roots.

In one of her more recent works, Bearing Witness, Tribute to Mendel Grossman, Kupferminc connects to her father's birth town of Lodz, Poland with an homage to the Jewish ghetto photographer Mendel Grossman, who was employed by the ghetto authorities as an official propaganda photographer. He also secretly recorded the destruction and suffering in the ghetto by placing a camera under his coat, a subversive act of resistance that Kupferminc re-imagines in her work.

Kupferminc’s work falls somewhere between a document of historical events and a reflection of her experience as the daughter of survivors, a second-generation witness. She transforms her work into a memorial and her public into new witnesses.

Each of these five artists approaches the Holocaust and its memory differently, yet they all enrich our understanding of the Shoah. From works made as a symbol of resilience or resistance to those that document the war to still others that spark conversations about social justice, these women used their art to hoist the flags of inclusion and empathy. We can learn from their art and their lives to say Never Again.

A few examples of Grete Stern’s commercial work currently can be seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in an exhibition running through August 4, 2024. The title is The Real Thing: Unpacking Product Photography.

Cada cuadro nos interpela. Recordar, nuestra memoria siempre debe estar presente.