Grace Paley and the Quiet Power of Friendship and Resistance

“My friends are dying,” Grace Paley begins her poem Sisters. She continues, “well we’re old / it’s natural.”

If you’ve never read any Paley, these first lines might feel crushing, even defeatist. But Paley, who devoted her life to Jewish leftism, means nothing of that sort. Instead, it becomes clear that her quiet attitude towards her friends’ passing is actually rooted in resistance. She knows there’s not much her friends could have done to fight off death, but their “little killing bugs and baby tumors” are pesky and miniature, rather than sweeping and mystical. It’s true, her friends are dying, but that concept cannot encapsulate them: “the word dead is correct / but inappropriate.” Her friends transcend death.

This month marks the 102nd anniversary of Paley’s birth, and though she, too, has now passed, this poem has provided me with a great deal of comfort in recent months. It’s perhaps ironic to say this as a 24-year-old woman, surrounded by my healthy friends in my lively Brooklyn neighborhood brimming with young lefties. I walk to the park and to shops, to the grocery store, to the pharmacy, weaving through everyone else doing the same. We are all very much alive: figuring out careers, selecting and appraising partners, maintaining or pruning relationships, considering the ways we want to spend our hours and days. We are lucky to possess this aliveness, and yet, bearing witness to the world is often a burden. Our money—which my friends and I truthfully make little of, working as teachers, social workers, students, and at nonprofits—is used against our will to drive ethnic cleansing, fascism, and hatred. A man who has been publicly accused of sexual misconduct at least 26 times is set to take the highest office once again, posing new dangers to already-marginalized populations. And in our own lives, we face loss, change, uncertainty. We ourselves are mostly considerably privileged, with supportive families and food and education and resources, and yet there exists a continual—and seemingly thickening—fog of heaviness, of injustice, of unknowns.

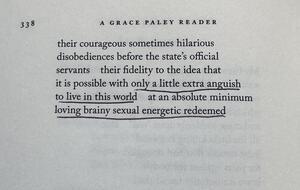

For Grace Paley, a late twentieth-century Jewish anti-war, anti-occupation, feminist writer, activism was at the core of her identity. So, too, were her female friends, she reflects in this late-in-life poem. Not permanently gone, instead just physically “absent,” she insists in Sisters, “their fidelity to the idea that / it is possible with only a little extra anguish / to live in this world” keeps her tethered. Her friends are kaleidoscopic and brilliant: “loving brainy sexual energetic redeemed,” with a “lightheartedness which floated / above the year’s despair / their courageousness sometimes hilarious.” Resistance and female friendship, to Paley, are inextricable.

When I think about “the year’s despair,” I picture attending protests, reading, writing, giving mutual aid, volunteering—none of which I feel like I do enough, honestly, and which sometimes even feel futile. At the same time, I think of the floating, interpersonal lightheartedness that Paley extols in her poems. My friends and I discuss books written by women and nonbinary people, take walks across New York City boroughs, watch arthouse films and trashy TV, collapse on each others’ couches, boil pasta and toss salads and scramble eggs and drink wine. There are certain powers in this world that seem inevitable or “natural,” like dying, but there are also forces to keep fighting against. Meanwhile, my friends are loving, brainy, sexual, energetic, redeemed, and alive. The solace we find in each other is a tiny, transcendent gift.