How a Trip to Ukraine Helped Me Decide to Have Children

After seven years with my spouse and still no desire to have children, I began to wonder if there was something wrong with me, something unmaternal. I’d previously been attributing my hesitation to a myriad of superficial reasons. Although my husband, Danny, and I were in our early thirties, no one in our Chicago friend group had any children. When conversations with my husband prompted me to think about kids, I mostly worried about the physical discomforts of pregnancy and that I would no longer have time to write. There were fiscal concerns, too. Danny and I had very unstable incomes—he a musician, me a writer—but even when our lives stabilized financially, and he wanted to start trying, I still found myself unsure.

My husband was not the only one asking me about these qualms. My grandpa Nikolai had already started a college fund for my distant-future child. Older cousins inquired at weddings. During one trip to Israel, where Danny was born and raised, my mother-in-law left an article open on the dining room table with a list of ways one can tell if they are ready to have children. Most of the reasons listed were obvious, and I had no issues with. But there was one that struck me: acceptance of your own childhood. Not that it was over, exactly, but that you had accepted the problems and pitfalls that had come up during those fundamental and often turbulent years.

Had I accepted them? As a Jewish refugee of the former Soviet Union, my own childhood had been tainted by our immigration to the US at the tender age of five. I never stopped wishing to go back to Ukraine—the need to explain the hole moving here as a child had left was very possibly what had made me become a writer—but in a way, it had also kept me stuck in a childish frame of mind. It was a longing so deep it made me selfish; I focused so much on understanding my own emotional setbacks and flaws that I couldn’t imagine being so available for another human being.

When my husband and I began making plans to visit my in-laws in Israel a couple years later in 2017, I demanded a stop in my Ukrainian hometown on the way. I cannot recall exactly why this trip made me feel whole again. Was it seeing my childhood apartment, so small and dark and tired looking? Was it the widespread poverty I witnessed every time we left the center of the city? Was it the fact that no one even spoke Russian there anymore, only Ukrainian, a language I never understood? Physically, it was the same place I had called home as a child, but it was not really the same place. This new Ukraine had stores and cafes and open borders, freedom, opportunity. It was not really my homeland anymore. Of course I knew all this going into it; most of my writing until that visit had centered on this fact. But there’s a difference between knowing a fact and letting that fact materialize physically in front of you.

The complete absence of Jews, for example, was somewhat shocking. Sure, I knew the facts: Before the Holocaust, there were almost three million Jews living in Ukraine. When the war ended in 1945, less than a third were left. By the late 1990s, after the country’s borders opened, that number dwindled further. As of 2014, the Jewish population of Ukraine is recorded at under 70,000 people. Most of these are not in Chernivtsi. There were probably a dozen beautiful domed churches, but the only synagogue in Chernivtsi was closed due to a lack of patrons. When I went to try and find my great-grandparents in the nearby cemetery, I couldn’t. The Jewish cemetery was overgrown and unmaintained: The headstones were crashing into each other, and the trees and weeds grew between them with abandon. Nowhere was it clearer what had happened to my family, to every Jewish family in Ukraine. We had left for a reason after all. Ukrainians didn’t want us there. And did they even regret it? It was hard to say.

Shortly after returning home from this trip, my beloved grandfather Nikolai died. The combination of seeing Chernivtsi, followed by a sea of tombstones with my family name somewhere on them—and barely enough relatives left to have a proper funeral—struck a chord in me. So many bones underneath us, and even more that we couldn’t see. All the uncles and aunts and cousins that were never born because of what had happened to us, what continued to happen. Many had died in Ukraine during the war, but even after, for those few like my grandparents who had survived the camps, no one could afford to have that many children. Lack of food and constant persecution didn’t make Ukrainian Jews eager to create more people to feed. My father was an only child. My mother was one of two, and so was her mother. What I saw at my grandpa’s funeral was how easily our entire family could disappear into oblivion if we didn’t make up for all the losses perpetrated onto us. What I saw was the necessity of it.

In the end, it was good that I had waited until I was ready to have children because I got pregnant the first time I tried. Being pregnant was surprisingly fun. For the first time, it felt like my body was doing exactly what it was meant to do—a physical embodiment of what my brain had already figured out at that funeral. Since giving birth, I have enjoyed being a mom, too. I had expected it to be horrible and difficult and unrewarding. I had always felt a little physically anxious before, like I was supposed to be doing something else in life or going somewhere else—for years, I had coped with this feeling by smoking cigarettes—but after Alma was born, I no longer felt this way.

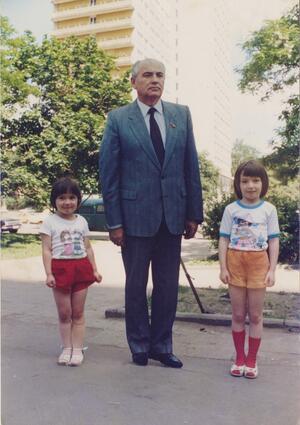

Having a child made me realize that it wasn’t Ukraine I had wanted back, but my family as a whole, the way that they had been in the 1980s before we left. During my early childhood, for the first time since the near annihilation of our people, Ukrainian Jews had begun to flourish and grow. My parents never had the chance to know their grandparents—they’d all died in the war or slightly after—whereas we lived with ours. In Ukraine, we had cousins and aunts and uncles all around us all the time; not working so much I never saw them, like my parents when we first immigrated; not rendered immobile by age and lack of language, like my grandparents their entire time in the US; not scattered around the country only to be seen again at weddings, like my aunts and uncles now. We were together, living our everyday lives, even in our unhappiness. Because we were Jews, it was a narrow window, and we—the generation who left as children—had missed it. The only place my family came together for more than a few days in America was in the ground. Immigration had saved us, but it also splintered us. With Alma, we were now our own little family, and perhaps a community could regrow from the splintered roots. Because, as I had learned so late, it was the tree itself and not the place where it was planted that was so important.

Zhanna, This is a beautiful essay exploring family, history and motherhood. Thank you for sharing it with the world.

Robin Stein, Newton, MA