Q & A with Filmmaker Allison Norlian about her new film "Thirteen"

JWA chats with filmmaker Allison Norlian about her new short film Thirteen.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

JWA: The film is inspired by your family's story. Can you tell that story?

Allison Norlian: I’m the youngest daughter of an Ashkenazi American mother and a Mizrahi Israeli father. My parents met in Israel, had my older sister Becky, who is profoundly disabled, and me, and then got divorced when I was four and my sister was ten. From then on, my mom raised Becky and me independently.

She was a single Jewish mother operating in a non-Jewish world and a Jewish world that, most of the time, felt like it wasn’t meant for her and our unconventional family. But despite the hardships put on us by the outside world, my mother advocated relentlessly for Becky, whether it was for more inclusive services and therapies or for her to reach milestones and have experiences like every other child.

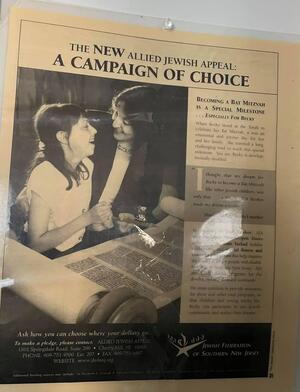

When my sister turned thirteen, my mom wanted Becky to have a bat mitzvah. At the time, no person with a disability had become a bar or bat Mitzvah at our Conservative synagogue. Luckily for us, when my mom approached our rabbi, he was receptive to the idea. (He’d gone on his own journey that would lead to that decision, a journey that began with him denying that there were disabled children in the community, but ended with him having a disabled grandson and my mother helping him through the acceptance.)

So all this to say, my sister’s bat mitzvah was one of many situations where I saw my mother’s advocacy—where I saw her see an issue, raise her concerns, ask for something, and receive it, which ended up creating a better, more inclusive environment. My mother taught me that you don’t have to accept the status quo and that you can create change in this often backward world. This is a lesson I’ve lived by as I’ve continued to advocate for disabled people and other underrepresented and misunderstood communities; this is a lesson I wanted to portray in Thirteen.

As you said, Thirteen is inspired by real-life—more specifically, by Becky’s Bat Mitzvah. More than two decades ago, my older sister Becky was the first non-verbal, developmentally disabled person to have a bat mitzvah at our synagogue. It wouldn’t have happened without my mother’s advocacy and insistence that my sister experience milestones like every other Jewish child.

JWA: There's a scene in the film where the mother, Leah, proposes the idea of a bat mitzvah for her daughter, Yael, and the rabbi initially refuses to even entertain the idea. Leah brings up Judith Kaplan being the first girl to have a bat mitzvah 100 years earlier. What, for you, is the connection between what Kaplan did and what Leah wanted for her daughter (and what your mother wanted for your sister)?

AN: Judith Kaplan is an example—not just for the Jewish community, but for every community that relies heavily on traditional values—that tradition can be altered to be more inclusive, and that being inclusive doesn’t take away from the tradition, but adds to it. Judith Kaplan set the trajectory for Jewish girls to have bat mitzvahs in the US, and Becky Norlian—whether we knew it at the time or not—did the same thing for the Jewish community in South Jersey. So I would say, drawing the comparison between Judith Kaplan and Becky was pretty important to Thirteen’s story.

JWA: You've written that the rabbi in the film was an "amalgamation of different roadblocks" your family experienced in the Jewish community because your family wasn't traditional. Can you describe some of those obstacles?

AN: The rabbi was an amalgamation of different roadblocks my family experienced, but he was also based on the experiences of other Jewish families we know with disabled loved ones back in the ’90s. Thankfully, so much has changed, but these memories shaped both my advocacy and themes in Thirteen.

Despite being proud Jews who attended synagogue regularly when I was a child, my family often felt like we didn't belong. I was the product of divorced parents, as I said earlier, and my mom was a single mom, so we struggled financially. Because of this, I often felt like an outsider among my peers in Hebrew school and among the non-Jewish kids in my public school.

When it came to being a part of the Jewish community, it was very expensive for us to belong to the synagogue and the Jewish Community Center, and for my mom to send me to Jewish camp. My mom ended up being part of a scholarship program so I could go to camp, but because she wasn’t a full-paying member, we had limited access to the JCC and had to go out of our way to another town to use certain amenities, which was impossible for us because of our situation.

Being the sister of a profoundly disabled person constantly contributed to me being on the periphery. I couldn’t go anywhere—in the non-Jewish or Jewish world—without seeing the stares and hearing the negative/derogatory comments when people saw my sister vocalizing or stimming. We always KNEW we were different because of what people around us said and did.

We were outsiders and we were alone.

JWA: Because of your sister, your family has been involved in disability advocacy in the Jewish community and beyond for decades. Can you talk about that work?

AN: When I was a child, we volunteered for organizations like The Special Olympics, and at my sister’s school for people with disabilities, we volunteered at their golf tournament. We raised money and participated in walks for autism/disability awareness and multiple sclerosis (my grandmother was physically disabled due to MS).

But most of all, we lived our lives by always including my sister, to expose the world to people with disabilities and allow my sister to live a “normal” life. My sister is nonverbal but vocal and vocalizes loudly in public spaces. Because of this, we experienced rude stares and comments. At one point, my mom, an artist, made shirts for us all when we went out. My sister’s shirt said, “I’m autistic. What’s your problem?” Mine said, “My sister is autistic. What’s your problem?”

My mother was open and always available to speak to people whose children and grandchildren were diagnosed with disabilities, to help them navigate this new world and the red tape they would eventually face. I always spoke up when I heard people use the R word or make derogatory comments about people with disabilities.

An example of my advocacy was in seventh grade when my English class was reading the book Flowers for Algernon, which features a disabled character. One day, while reading the book in class, a group of students started making fun of people with disabilities. I went home crying, and my mom said, “So what are you going to do about it?”

I ended up giving multiple presentations in my classes with my mom and sister present, explaining disability culture and the need for my fellow students to understand why their words and actions were hurtful and harmful.

Those presentations were my first but wouldn’t be my last.

In my adult life, I went into journalism to further my disability advocacy by working tirelessly to tell stories focused on the disability community. At the various TV stations and digital outlets I worked for, I shared countless stories amplifying people with disabilities that impacted laws and policy in my community. Because all my journalism focused on the disability community, I won a Catalyst For Change award from the ARC of Virginia, an advocacy organization. I also was nominated for an Emmy for a piece of journalism that focused on adults with disabilities, mental health struggles, and older people.

Now, my advocacy continues through my filmmaking.

JWA: What changes have you seen over the years in attitudes toward disability inclusion in Jewish communities?

AN: According to my mother, who’s been involved in this space longer than me, when my sister was born in 1983, there was nothing available to her in the Jewish community in southern New Jersey, where she lived. The only spaces with services/options for her and Becky were Catholic-run charities and centers. My mom used these centers, but also questioned the Jewish community she was part of to see why there was nothing for families with someone with a disability.

Not much happened until a few years after her questioning, when a focus group was started at the Jewish Community Center in southern New Jersey called Open Hearts, Open Doors. Their primary purpose was to bring special needs children to JCC camps. However, they discussed future options such as group homes, activities, programs, etc.

Eventually, things started happening, as more people came forward who were Jewish with disabled children. Now, the Jewish community in southern New Jersey is full of opportunities for people with disabilities; there are group homes, day programs, activities, camps, nonprofits, etc. According to my mom, it still isn’t perfect, but today, inclusion is leaps and bounds better for people with disabilities in the Jewish community—and outside of it, too.

JWA: I read that the actress who plays Yael has autism. Was it important to you that the character was played by someone with a disability, and if so, why?

AN: It was extremely important to me to cast Thirteen completely authentically. All the Jewish characters were played by Jewish actors, and the role inspired by my sister was played by Naomi Rubin, a wonderful Jewish actress on the autism spectrum.

Although one in four people are disabled in the United States, and over 1 billion people are disabled worldwide, representation of disabled people in the entertainment industry is sorely lacking. According to the Ford Foundation's 2019 Road Map for Inclusion report, the fraction of people depicted with disabilities on TV and in movies is much lower than in reality. When disabled characters are depicted, they’re typically played by non-disabled actors.

That’s why for Thirteen, we cast a person with a disability to play the role inspired by my sister. It’s also why for any narrative film I write and create in the future, I will always cast authentically. Not only is authentic casting important for representation and inclusion, it’s also a creative and artistic imperative. People with disabilities have a unique point of view and experiences that can best serve their stories, and I wanted that perspective in Yael’s portrayal.

JWA: What are you hoping audiences take away from this film?

AN: When I was growing up, I never felt seen or understood. I felt like an outsider in the world because I’m Jewish, the product of divorced parents, and because I have a profoundly disabled sister. And in the Jewish world, my family and I often came up against feeling ostracized. As I was growing up, I had no role models or stories to make me feel seen or to know that I wasn’t alone.

So through my work as a journalist and now as a filmmaker, that’s what I’m trying to do. I hope other people who encountered this situation or something similar feel less alone and I hope it’s a learning experience for everyone else.

I also hope people see the beauty in Jewish life, and how inclusion doesn’t take away from tradition, but actually adds to it.

I hope this film changes hearts and minds and helps with my goal of changing the way the world views disability.

JWA: Where can people learn more about Thirteen, and most importantly, when and how can they see it?

AN: People can follow us on Instagram @thirteen_short_film or at my company’s website. There is also information on our Seed and Spark fundraising page.

Right now, we’re just doing private screenings while we participate in the film festival circuit but hopefully the film will be distributed somewhere for wider release soon!

By reading your article i feel like it came from the heart God bless you by the way today i had lunch with your dad