Q & A with Poet Aurora Levins Morales

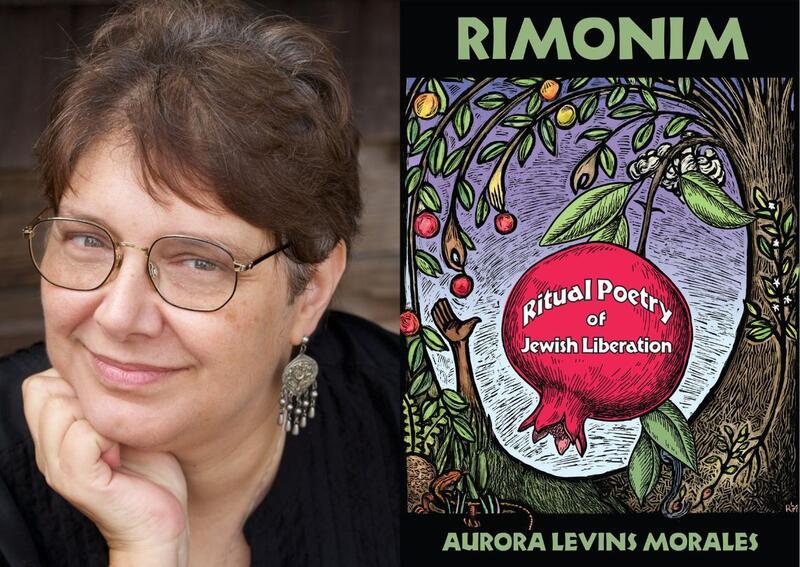

JWA talks to poet Aurora Levins Morales about her new book of poetry, Rimonim Ritual Poetry of Jewish Liberation, and considers the power of protest, prophecy, and music in these times that call us to action.

JWA: You are a child of revolutionaries. Can you tell us more about this fascinating heritage?

Aurora Levins Morales: Revolutionaries are people whose lives are organized around a commitment to build a world of justice and reciprocity. I have ancestors and relatives on both sides of my family that lived this way, and on my Jewish side, a lineage of at least six generations in a row. For me, this was a core element of my Jewish identity, one that was very strong among Eastern European Jews in general. My grandmother’s great-grandmother was the wife of a rabbi in Kremenchuk, on the Dnieper River in Ukraine. She had studied Torah and was a better scholar than her husband and protested that she could not become a rabbi herself. The men of the shul told her it was God’s law, and she responded, “Your God is a man,” and walked out, taking the rabbi with her.

Her granddaughter, my great-grandmother Leah, said the rebbetzin was the one who “planted the revolutionary spark” in her. She was a feminist and a labor organizer in Brooklyn. My parents met at 18, at a Communist Party social event. My mother had discovered Marx in college and said his ideas made sense of her life as a working-class Puerto Rican. They were both proud of their cultural heritages, and they were not nationalists. They didn’t fight only on behalf of their own people. They wanted the whole world to change. They were blacklisted, moved to Puerto Rico and became part of the movement for Puerto Rican sovereignty, and later, in the States, were involved in many movements. I grew up knowing a lot about the ongoing Cuban revolution, which I got to witness at 14, about Vietnam, feminism, Black Power, the many efforts to throw off colonialism. The vision of possibility and hope that they built their lives around has shaped every aspect of my own life, including the flexibility to keep defining those things for myself.

JWA: You write of your Jewish heritage and your Indigenous ancestry. What are some of the ways that your heritages overlap and reinforce one another?

ALM: My maternal heritage is Puerto Rican, which includes Caribbean Indigenous, North and West African, Iberian, and probably some Arab. So Indigenous heritage is one part of my mother’s ancestral line, and I have inherited threads of those ways of being. But, like many Caribbean people of Native ancestry, although I grew up knowing and celebrating this, I was not raised within a tribal culture, and am very careful not to allow confusion between what is actually true about me, and what is true of people who are claimed by their contemporary native family and tribal leadership. There are many people raised completely outside tribal cultures, who claim indigenous identity without any relationship to or consent from the tribal communities they say they belong to. Only those communities get to grant membership.

That said, I don’t experience my Jewish and Puerto Rican identities as separate enough to overlap. The kind of Jew I am is a Caribbean one with 4,000-year-old roots in these islands and much older ones in “the Americas.” The kind of Puerto Rican I am is a Jewish one, with an Ashkenazi father and hidden Jews sprinkled through my Spanish family tree, a Jew raised in a very Christian-dominated Puerto Rican society. It’s other people who find this confusing. I do not.

JWA: In your new and beautiful poetry collection you give voice to Miriam: “Aren’t we all prophets.” What does it take to be a prophet in the turbulent and chaotic times in which we find ourselves?

ALM: I think “prophet,” like “elder,” is a name others give you, not one you give yourself. And like “revolutionary,” it’s a way of living, especially in turbulent and chaotic times. Prophecy is the work of speaking truth, with as much clarity, power, and beauty as we can, about two realities. One is what it’s like for humans to exist in the world as it is right now, and the deepest stories we can find about how it got that way. The other is the story of our beautiful humanity, our ability to stretch toward each other, the huge power of our imaginations to keep dreaming of other ways to shape the world, other possibilities. What is and what could be.

So what it takes for me is to take very good care of my hopefulness, to treat it as a precious part of the commons that I steward, to stay connected to people who help me hold all this, to listen deeply to my innermost voice and the voices around me that resonate, to draw on the natural world and keep reintegrating myself into it, and take seriously and joyfully the importance of what art can do for our ability to stay human in inhuman conditions.

JWA: Your poems use the verb “dowse” —which is not a word we hear very much these days. What does it mean to you and how do you bring this practice into your life?

ALM: I think it’s another way to describe listening for and trusting what my body, the land, the ecosystem I belong to, are saying. Dowsing, as traditionally practiced, is about finding underground water by tuning in to the ways a wand of willow or some other trees respond to the presence of that water. Very subtle changes that we learn to feel. I describe my creative process as dowsing, wildcrafting, composting—I listen, I gather, I simmer, what sings to me, or resonates, or demands my attention if I am quiet enough to hear.

JWA: Your work connects us to sacred traditions from traditional herbalists. You say, “I write my midrash in color and thread and the cooling water.” Your poetry evokes a way of seeing ourselves as part of nature. How does your work as an herbalist inform your poetry and spirituality?

ALM: I don’t necessarily name myself as an herbalist. It’s not a primary outward-facing practice for me, but I have been making and using plant medicines for over fifty years as a central survival strategy to deal with chronic illness, disability, and the stresses of our oppressive society, so it has become one of the many languages I speak, along with those of color, of water moving across landscapes, of fibers, fabrics, weaving. In my book Remedios I retell a vast tapestry of history centered on Puerto Rican women, and I incorporate many voices of medicinal and food plants, speaking as interpreters and commentators on the human stories.

JWA: Who are your poet matriarchs and patriarchs?

ALM: I’m not sure I would define the writers who have most opened a way for me as “archs” of any kind. Teachers, guides, givers of permission, the ones who make me want to write immediately. Some are song lyricists, some poets, some novelists or essayists. Most of the ones I’m listing today (the list is always shifting) are ancestors now, no longer breathing through their bodies, but still breathing in our universe. A few are still alive and sparking me into creativity. My list is much longer than this, but this is my selection for December 25, 2024.

First of all, my mother, Rosario Morales. Adrienne Rich, Ursula LeGuin, Nicolás Guillén, Pablo Neruda, Paul Simon, Leonard Cohen, Judy Grahn, Susan Griffin, Bertolt Brecht, and Raúl Valdes Vivó have been with me since my teens. Then Audre Lorde, Toni Morrison, Pat Parker, June Jordan, Violeta Parra, Sara Gonzalez, Silvio Rodriguez, Sean O’Casey, Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, Minnie Bruce Pratt, Muna Lee, and a few that I recently re-encountered, Nalo Hopkinson, Julie Otsuka, and Chris Smither.

JWA: One phrase from Rimonim which echoes for me is “a sweet year of struggle”. As Jews and as women, how can we resist the patriarchal systems and fascist governments that we are faced with?

ALM: Many different ways. We have very ample toolkits. We need to have open, welcoming conversations that aren’t looking for THE strategy or priority, but enriching our collective soil so that many ideas can thrive together. As Audre Lorde told us, we find the work that is ours to do, and we do it. Not the work someone else thinks we should do. As a Cuban psychiatrist in Havana told me, find people who share your values, find important work to do together and have fun doing it. We build circles of people who are both friends and comrades, we treat each other well, we study the past and learn from it, we cross borders of all kinds, we keep imagining together the world we want and feed that imagining, we move through the world guided by that vision and by our principles and are flexible in the moment about how they will guide us. We do work that feeds us as well as the world, learn to be swift but not urgent, think about seven generations behind and before us, and remember that people have been resisting male domination, repressive regimes, the extraction of resources necessary for our lives, war, and ecological destruction for centuries. If we resist all temptation to use the masters’ tools to unmake the house of domination, we can do this.

JWA: “Let justice be my song,” you write in Rimonim. What role do music and protest play for you?

ALM: Music is a big mood adjuster for me. I listen to a lot of music from the New Song movements in Latin America to feel connected to that revolutionary history that lives in me. I listen to blues and folk and what used to be called “New Age” instrumental music. I listen to different regional music mostly from western Africa, and a lot of the newer Jewish musicians creating liturgical/sacred music. I like listening to Jewish music from all over the world, how Jews of Color sing. Like plant medicines, there are particular songs or artists that move my energy where I want it to be. The only music I listen to while I’m actually writing is that of Will Ackerman. I’ve been writing to his music for 40 years, so I have a conditioned art trance response to it.

JWA: What’s next for you?

ALM: My collaborators and I are working on an audiobook version of Rimonim, and well as a teaching guide, to help that project move into the world in different ways. A book of my collected works, The Story of What is Broken is Whole: An Aurora Levins Morales Reader, also just came out,and I'll be working to it get into more people's hands. I have a whole mosaic of interwoven,explicitly Jewish projects. One of my favorites is building relationships with the congregation of Temple Beth Shalom in San Juan, Puerto Rico, where a few of us hope to start an oral history project about Puerto Rican Jewish lives.

My work often moves between the intimately personal and the global, and my newest project takes on my epilepsy, which I believe was caused by pesticide exposure, as part of the larger story of neurotoxicity in the world. Many pesticides are closely related to military nerve gasses. These classes of chemicals are all created for control. It also turns out that there are bacteria that help to remediate the poisons in our bodies and the soil, through fermentation! Ferment combines creative writing and visual art to explore the dangers of these chemical assaults and the medicine we can make to heal them, at every level, from body to planet.

As artists, we’re often expected to talk about our work separately from the rest of our lives, so I want to bring all of me here. I live with a lot of deep fatigue and muscle pain, drug-resistant epilepsy and diabetes, just for starters. Being a radical female artist doesn't come with a pension, so my community continues to be my real social security. I am actively organizing a virtual book tour through speakoutnow.org to build up my reserves. Over the last five years, I've been living on family land in Puerto Rico, building soil, planting fruit trees and food gardens. So, my biggest project for the coming year is to stabilize my health, my finances and my food gardens. People who want to help me do that, as well as continuing to write, can do so through my Patreon page.