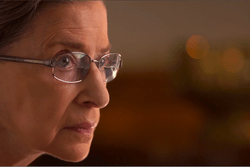

How Do You Mourn an Icon like RBG?

There are significant benefits to composing a piece of writing about the death of a titan over two weeks late. By now, Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death has been analyzed ad nauseam along familiar fault lines and the Justice herself has been tropified: universal feminist icon, faultless hero, (flimsy) bulwark against an irreversible slide into Margaret Atwood’s Gilead. Some are filled with rage that she didn’t retire under the previous administration; a few remind us that hero-worship of any public figure is rarely productive and virtually never earned. Over the last few weeks, I’ve found myself careening wildly across the spectrum of responses, rolling in waves of panic and calm while trying to come up with a new, sexy way to say, “I’m angry.”

On that Friday, I was stirring a cocktail and watching my apple and honey Bundt cake rise when I received a text from a beloved mentor telling me to check the news. I had just wished her a happy new year while eyeballing my bourbon pour rather than using a measuring glass. My phone dinged with texts in rapid succession. “Did you see the news about RBG?” my mentor wrote, followed by a string of broken-heart emojis. I closed my eyes and grimaced, my reflexive habit when I’m sure I’m about to teeter off balance. I didn’t have to turn on the television to know she had died. Later that night, scrolling Twitter, I watched writers, journalists, and pundits hit their preordained marks beautifully—here’s a list of RBG’s best jabots; here’s a thousand variations of the same (well-intentioned) misunderstanding of Talmudic law; here’s people arguing about whether or not it’s offensive to leave flowers instead of rocks in memoriam.

Twenty hours after her death, the news cycle fixated on the inevitable: Trump was going to nominate a woman (how generous) to fill RBG’s Supreme Court seat. As expected, his choice was the fervently conservative Amy Coney Barrett, someone all but certain to overturn Roe v. Wade if given the opportunity. The day the nomination leaked, a few hours after RBG was fully laid to rest, I sat in front of my computer staring at a blank Word document, paralyzed by my inability to write something kind or helpful or hopeful.

Did it have to happen this way? The question of whether RBG should have stepped down from her post during Obama’s second term is fraught; a great number of deservedly tired women have noted that it feels impossible to imagine the same vitriol directed at a male justice keeping his lifetime appointment. But the Supreme Court is not a nonpartisan space, untouched by the messy realities of political maneuvering. We know now that President Obama himself floated the suggestion of retirement to RBG in 2013; she, like so many of us, expected Hillary Clinton to trounce Donald Trump in 2016. Hindsight is cruel.

Truthfully, I don’t gain much from ruminating on how RBG could have handpicked her replacement, as Justice Kennedy did. Nor does it alleviate my sense of impending doom to compose and delete tweets that take aim at the members of her fanbase that worked to elevate her into a pop cultural icon beyond reasonable criticism. Valid, exasperated, and frantic critiques of RBG’s choices and legacy speak to the deeper problems of our judicial system. RBG was not wholly good or wholly bad—she’s a conduit for our deeper fears about losing what little, merciful ground we currently stand on.

Much of my writing paralysis about RBG stems from a fear of disappointing or wounding the Jewish women in my life for whom her very existence was a source of hope. But RBG was a public figure, whose career had tangible effects on the American people. In 2013, a Tumblr blog created by a law student dubbed her the Notorious RBG, after the late rapper Notorious B.I.G (an association that feels inappropriate, as many Black writers have noted). As her dissents gained Internet traction, propelling her to pop-culture icon, so grew the idea that her avoidance of death was the only thing preventing the United States from total legal chaos. For Bitch, Rachel Charlene Lewis writes, “Even if you knew nothing about the Supreme Court, Ginsburg’s sudden transformation into a pop culture must-watch meant that she was no longer just a justice. She was a celebrity. And, perhaps unsurprisingly, the latter carried more weight.” What a terrible burden resting on one woman’s shoulders. But the political burden is one she took on willingly—RBG certainly understood the gravity of a Supreme Court appointment.

My thoughts are evenly and maddeningly split between recognizing the incredible journey Ginsburg undertook to rise to the position she held and understanding that seeing RBG as an uncomplicated folk hero is primarily the domain of white, upwardly mobile women. This is not to insinuate that RBG’s shortcomings (on Native sovereignty, on Black Lives Matter, on immigration, etc.) were unique; they simply had far reaching real-world consequences.

This, too, RBG must have known well—which is why she made public apologies on a number of occasions for both off-the-cuff comments she made and votes she cast that ran directly contrary to her espoused values. The tension between who RBG was and who we wanted her to be is a direct result of the pop-culture pedestal we built and maintained for her without much input from the woman in question. “In death,” Lewis concludes, “the memeification of Ginsburg fails her... it feeds into criticism that should be of our response to Ginsburg, rather than her own ethics and personhood. She didn’t name herself Notorious RBG—that’s on us.”

The timing of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death has meant, from a pacing standpoint, that we haven’t had much time for thoughtful, nuanced reflection. We’re under a hurricane that’s stalled out, our proverbial houses ripped apart to their skeletal foundations. This year in particular has robbed me, and virtually everyone I know, of the ability to feel surprised or even appropriately apprehensive. All we can do now is look to our immediate communities and ask ourselves how we’ll show up for the rights we deserve. We can’t look to the courts to give and take autonomy, or justice, or freedom. After all, for millions of people across the country, abortion has long been effectively illegal, by way of closed clinics, financial burden, and convoluted state laws about fetal viability.

I am hopeful for the moment in the future when I can think about Ruth Bader Ginsburg from a place of relative mental stability, rather than a state of fight-or-flight. She knows peace now—I wish us the same.