The 21st Century Scarlet Letter: A Look at How the High School Rumor Mill Affects Teenage Sexuality

I was a sophomore when I first stumbled across Easy A on my Netflix browser one lonely Friday night. The green poster, exclaiming in bold lettering, “Let’s Not and Say We Did,” was the first thing to pop up under the “Top Picks For Hannah” banner. It instantly grabbed my attention. Intrigued, I clicked play. Two hours and a bowl of popcorn later, I sat staring at the bright light of my computer screen, simultaneously uncomfortable and fascinated by the film’s portrayal of female sexuality.

In a nutshell, Easy A is a teen comedy about a girl named Olive who lies to her best friend about losing her virginity, and suddenly becomes the focus of her school’s gossip mill. When a gay friend asks her to pretend to hook up with him to save him from bullying, she agrees, and soon goes into business as the “school slut.” Boys soon come to her asking for similar favors in exchange for money and gift vouchers. Meanwhile, the school’s “Jesus Brigade” spreads terrible rumors about her sinful behavior. It’s a social commentary on high school’s penchant for gossip, and hits the nail on the head in terms of the realities of slut-shaming. And I love its brutal honesty.

This movie was my first introduction to the world of teenage promiscuity. I, a token “nice girl,” had never even held hands with a boy, let alone had sex with one; which is not to say that I knew nothing about sex. I was, after all, fifteen, and my parents, two medical anthropologists, never shied away from discussing sex with me. It’s just that my friends and I never really talked about it, and sex ed in Florida is basically, “Let’s practice Abstinence 101.” So, socially speaking, sex was a foreign concept to me, which is exactly why watching Easy A was so life-changing. It portrayed this significant social taboo and the issues that accompanied it so openly that I started to view teenage relationships in a completely new light.

Even though I may have appreciated my newly acquired knowledge, as well as Olive’s carefree and take-charge attitude towards her newfound notoriety, the film is still overwhelmingly problematic. For one, it reinforces the double standard when it comes to women’s sexuality. Before they pretend to have sex at a party, Olive tells Brandon that he should be prepared for the consequences. Yet, when they emerge from the bedroom, Brandon is met with high fives and excitement from the other guys. Olive, on the other hand, becomes a social pariah and is criticized heavily. Why are boys extolled for having sex, while girls are shamed for it? This double standard is not exclusive to Hollywood movie sets; I see it so much at school and on social media. As a flourishing feminist, I’m outraged that this double standard exists, and I think the movie only solidified it, rather than identifying it as a problem and condemning it.

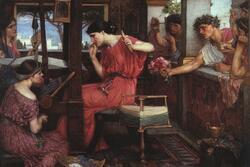

Slut-shaming and ostracism are by no means modern concepts. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, upon which this movie is based, portrays a woman charged with sexual promiscuity, Hester Prynne, as a stain on her seventeenth century Puritanical community. So, Hester is punished and led out of town, forced to wear a scarlet “A” (for adulterer) on her chest. Inspired by this novel, Olive begins to wear a scarlet letter “A” around school as well; a sign of defiance to those who attempt to shun her. Unlike Hester who is made to wear the letter “A” as a symbol of her “deviance,” Olive makes a conscious decision to wear hers. Nevertheless, each may as well have the symbol branded on her once the rumors start flying. Whether in 17th century Boston or 21st century California, women simply can’t escape judgement.

Despite the ubiquity of the word “slut,” it’s rarely ever mentioned in relation to men. Sure, a sexually promiscuous man may be called a “player,” but never a “slut.” The simple fact of the matter is that men aren’t as readily judged as women are when it comes to their sexuality. And if they ever are judged, it’s in a positive way. A guy who leaves the home of a girl he’s just slept with knows he’s scored. A woman who does the same is forced to do the walk of shame. This standard is so ingrained into our society’s mind that we’ve even crafted “cute” phrases for it.

Easy A also perpetuates the idea that if a woman has sex with multiple people, then she becomes public property, and all men can feel entitled to her body. Olive is treated by the boys at her school like she owes them sex, like her body is not fully and solely hers, but theirs to use and then discard. This is beyond demeaning to women, especially those who are just beginning to discover their own sexuality. Rather than fulfill the twisted norms of a patriarchal society, women should be taught that their bodies can’t be used as pawns to determine men’s social standings. The fact that Olive has a booming business because boys think having sex with her will raise their social status is, in itself, problematic.

Teens love a good scandal to gossip about, and sex is always one of the hot topics. I don’t think that two people’s intimate relationship, whether real or fake, should be subject to external judgement. Learning about your own sexuality–especially as a young woman who’s already bound to endure more prejudice than her male counterparts–is a deeply personal experience. It shouldn’t matter to others when one does or doesn’t have sex. This film has taught me the dangers of judging others on how they deal with a concept as intimate as sex. In the words of Olive Penderghast, “I might even lose my virginity to him. I don’t know when it will happen. You know, maybe in five minutes...or six months from now...But the really amazing thing is, it’s nobody’s business.”

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.