The Daughters of Zelophehad and the Right to Broadband Internet

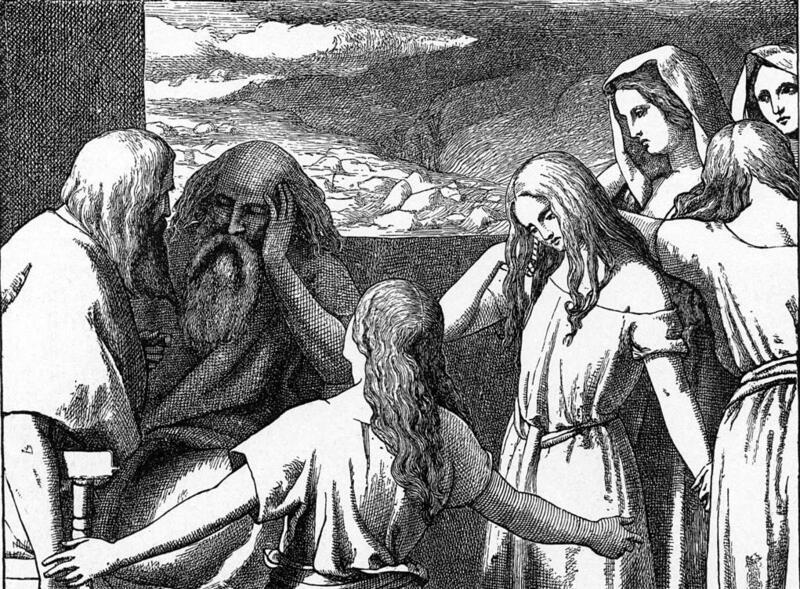

When I was young, my parents would often regale me with the story of my name, Noa. Despite there being a quite similar (and admittedly more popular) version of the name in Hebrew spelled with the letter vav, my parents’ choice was a conscious and, in hindsight, very important one. The story of my name stems from some of the first feminists of the Torah, featured in the book of Numbers: the daughters of Zelophehad. These five young women (including one named Noa) pushed for their rights in a patriarchal social and legal system. The sisters approached Moses, the leader of the Israelites, and demanded that they receive their father’s land after he died. Until that point, women in the Torah weren’t considered full citizens, much less seen as eligible for land inheritance. Noa and her sisters unreservedly asked for men to fundamentally shift how they viewed women as they pushed for something that, at the time, wasn’t recognized as a woman’s inherent right.

I've come to understand that making firm demands, even if they push societal boundaries, remains important today. The foundation of historical and contemporary activism is based on pushing for change ahead of the general conscious. Activism is demanding for a perceptual shift in what is considered a human or legal right. Yet there has been hesitancy, by governments and citizens alike, over one right that has come to define this generation: broadband internet access.

It seems that, in the minds of many Americans, broadband internet is a privilege—something only those who can afford it are entitled to—rather than a right for all. But as the world has continued to modernize, and the pandemic has transformed much of the real world as we know it into a virtual one, it has become increasingly clear that broadband access has profound effects on socioeconomic mobility and on an individual's ability to participate in our rapidly-changing world.

As the gap between socioeconomic classes continues to grow, being able to “connect” is more critical than ever. In his 2019 article, “The Human Right to Free Internet Access,” Dr. Merten Reglitz states, “Without such access, many people lack a meaningful way to influence and hold accountable supranational rule-makers and institutions. These individuals simply don't have a say in the making of the rules they must obey and which shape their life chances.” Studies have shown that, with political discourse occurring online more and more frequently, broadband access is key to protecting human rights, promoting free speech, and holding governments accountable on a global scale.

At a national level, the ability to access equal education is a guaranteed right under both the UN Declaration of Human Rights and the US Constitution. Yet, given the now widespread implementation of “Zoom school,” students who are unable to purchase broadband are at an inherent disadvantage. Though the long-term effects of the education disparity resulting from the pandemic are unknown, as more schools have taken initiatives to utilize online learning tools, the need for students to have equitable access to the internet has only grown.

There has been a push for greater broadband access by organizations like EDUCAUSE, which partnered with 29 different higher-education institutions in penning a letter to Congress to advocate for the Supporting Connectivity for Higher Education Students in Need Act (which passed into law). Yet, though there are examples of success, the issue has been largely overlooked on a greater scale.

Contemporary activists should heed the lessons from the story of the daughters of Zelophehad; the most important aspect of Noa and her sisters’ story revolves around their boldness in pursuing something that seemed unachievable. A perceived unattainability dissuades many of us from seeking meaningful change, but Noa and her sisters can inspire us all to work for what we know is right, not just what we think we can achieve.

Although providing the world with accessible broadband may seem like an impossible task, it doesn’t make this issue any less pressing. It may be daunting to make a demand for something that’s seen as a privilege, but social movements have been doing it for centuries—ever since Noa and her sisters' time. Let’s take a page out of Noa’s book and support the promotion of equity. Let’s make the daughters of Zelophehad proud.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.