How Judaism Fuels My Commitment to Reproductive Rights

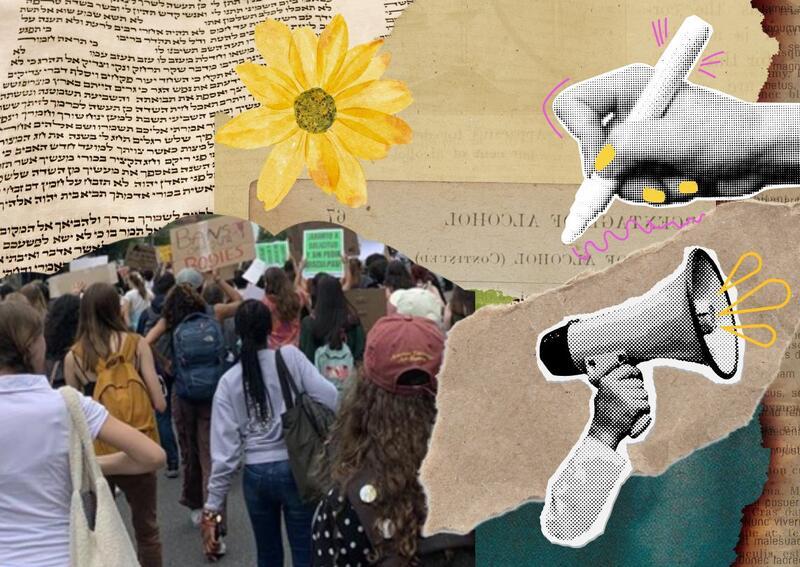

As a kid in a relatively traditional Jewish community, I grew up seeing feminism and Judaism as two separate entities. That all changed in 2022. When Roe v. Wade was overturned, I participated in the uproar of protests, and I learned that these two core parts of my identity could coexist.

As the president of my school's Women Empowerment Club, I took it upon myself to ensure other teens felt they, too, could speak up during this challenging period. Upon hearing about a student walkout in Manhattan, I approached my school’s administration and successfully exempted all those interested in attending the protest from class.

I feel privileged to attend a pluralistic day school with many others who share similar views to mine, where I am recognized as an equal in a Tfillah space and in a classroom. I learn from female Rabbis and female STEM teachers. Yet, as I skipped my Judaic studies classes to attend the rally on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, I felt as if I was giving up one part of my identity for another. While I did not feel a distinct tension, I struggled to recognize any overlap between these two sets of values.

Attending the rally was eye opening for me. One of the chants I heard echoing the streets was “F- the Church and the legislature, I am not an incubator.” As protestors opposed Christian stances toward abortion, I asked myself: what do our Jewish texts say about abortion?

Interestingly, both the Torah and rabbinical law suggest that life doesn't begin until birth. The Torah provides a scenario where a pregnant woman is unintentionally harmed during a brawl between two other parties. If this causes her to have a miscarriage, the one who injured her must pay a fine. However, if she dies, the perpetrator would be executed by the court. Here, the Torah does not instate the ruling of a “life for a life” for the fetus, but only for the mother, and therefore does not consider the fetus to be a life in the way the mother is. The punishment for the loss of the fetus is less extreme than for the loss of the mother’s life, therefore implying the scenarios are not equatable.

The Mishnah takes a similar stance on a slightly different situation. Due to the lack of proper medicine at the time, childbirth was much more dangerous than it is today. The Mishna presents the following circumstance: “If a woman is having trouble giving birth, it is permitted to remove the baby limb by limb from inside the womb, since her life takes precedence. However, if the majority of the baby has come out of the womb, it cannot be touched since no life should take precedence over another.” It is reasonable to infer from both these texts that life officially begins at birth, therefore delegitimizing the argument that abortion is murder.

In 2021, the Conservative Movement’s Committee on Jewish Law and Standards released the following statement: "Neither viability [of the pregnancy] nor a woman's right to choose is the basis of Jewish law on abortion, although they play a role only indirectly; what matters in Jewish law is the woman's life and health, both physical and mental."

It would be naive to say that our ancient texts were grounding their rulings in women's bodily autonomy. However, as we progress and amend our traditions, we can take wisdom from past rulings to benefit the Feminist cause. As a feminist Jew, I admire that we can base our fight for women’s bodily rights in the sources that both my community and I hold as holy.

I am lucky to be in a community with Jewish leaders who are passionate about women’s rights. Senior Rabbi Angela Buchdahl of Central Synagogue in New York City became the first Asian-American to be ordained. Despite her hardships as an Asian woman, Rabbi Buchdahl continues to pave new paths for women in Judaism today. While Rabbi Buchdahl inspires me in numerous ways, her commitment to women's reproductive rights speaks to me in particular. Rabbi Buchdahl is a proud member of the Rabbis for Repro movement, a group of rabbis and religious leaders who believe abortions are an issue of Jewish morality. These rabbis pledge to use their platforms to “teach, write, and speak out about reproductive rights and Judaism in the United States and in the Jewish community.” Rabbi Buchdahl continues to use her voice to fulfill this promise and fights to put the rabbis' true words to fruition.

As I continue to explore the intersections between Judaism and women’s reproductive rights, I look to both ancient and modern texts to ground my complex thinking.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.