Studying the Holocaust as the Only Jew in Class

Content note: This blog post contains frank descriptions of Holocaust violence.

Right before my first semester of tenth grade, my mother warned me that there was going to be a unit on the Holocaust in history class. Even though I knew I would be the only Jew in class, I didn’t understand why she was warning me. I had been taking Holocaust studies at Hebrew school since I was eight years old, and I grew up with stories about family members who tried to make it out of Europe, some luckier than others. I knew from the start that I wouldn’t be learning anything new in that class, but I never would have guessed that they would be the most uncomfortable Holocaust lessons I had ever experienced—and at first, I didn’t even know why.

I had always been one of the only Jews in my area. In tenth grade, there were a record-breaking five others in my high school of over 1,300, and I had known four of them since birth. On the first day of our World War II unit, the student teacher asked us to write down everything we already knew. During the lesson, one student raised his hand and asked, “Wasn’t Hitler Jewish?” As I whipped around to look at him, the student teacher responded, “No, you’re probably thinking of Jesus. Because Jesus was Jewish, and the Jews killed Jesus.”

His answer caught me completely off-guard; my stomach dropping, and I could hear my heartbeat in my ears. Then I did something I had never done before in my life: I interrupted a teacher.

With the most authoritative voice I could muster, I answered, “Actually, the Roman government killed Jesus.”

My student teacher’s response? “Yeah, but the Jews wanted him killed.”

The only words I was able to say after that without my voice shaking were, “It’s way more complicated than that.” And with that, he dropped the subject, and it was never brought up again.

Thankfully, the rest of the unit went well. My teacher was very sympathetic to the fact that this was a difficult topic for me, and my friend kept giving me compassionate looks as we watched Escape From Sobibor. Even though the movie dealt with the theme of Jewish resistance quite well, there were many parts that came off as straight-up trauma porn. For example, there is one mass execution scene that lasts between five and ten minutes right after a baby gets shot at point-blank. There is also a disgustingly long shot of naked children getting shot outside a crematorium as screams and smoke rise from the chimney. I understand that the director had to show how cruel the Nazis were, but those scenes were so over the top they almost seemed cartoonish, and I felt physically ill while watching them.

But at the same time, I couldn’t stop thinking about my classmates spoke about the Holocaust no differently than if they were talking about the mythology of an ancient civilization. It felt as though none of it was real. For them it was just a history lesson, but for me it was so much more.

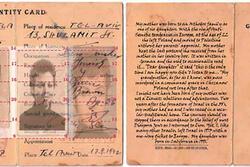

My bubbe was born in Uzbekistan in January of 1945 because that was where her parents happened to be while they were running through Europe on foot. I see her every single Shabbat. The police cars parked outside my synagogue since October 7 that I walk past every week are real. All of it is very much real, but I couldn’t figure out why it felt so not real in class.

My dad explained it well when he said, “When you’re learning about it with other Jews, you all have the same trauma that you’re all gently opening up to look at together. But when you’re the only Jew there, your trauma is being put on display to be ogled.” I don’t think I could have explained it any better.

None of my classmates had ever recognized their own faces in pictures from Holocaust documentaries or had nightmares about gas chambers. When we looked at photographs of little kids with Stars of David sewn to their coats, everyone else was either making comments about how tragic it was or avoiding eye contact with the screen. Meanwhile, I kept thinking that, since I had so many relatives who were killed, those pictures of the little boy with my nose, the woman with my mother’s eyes, and the girl with my cousin’s curls could have been us.

While it’s crucial for non-Jews to learn about the Holocaust, it’s emotionally exhausting to be in the room while that learning happens. That first day, the student teacher’s lesson was to write down a single word to describe the Holocaust (already an impossible feat). While my classmates wrote down “genocide,” “Hitler,” and “medical experiments,” I found my pen scrawling out the word “family” before defiantly underlining it.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.