Taking Inspiration from Urushi Trees on Tu B’Shvat

“Planting, cultivating, harvesting, making, using, and mending.”

This is the motto created by a group of artisans living in Keihoku, Japan, seeking to live in harmony with the nature they draw inspiration and resources from. This connection to nature is what inspired Sachiko Takamuro to co-found Forest of Craft in 2019, something that has made me consider the role of my own consumerism this Tu B'Shvat.

When traveling to Kyoto for a class trip this January, I didn’t expect to find myself at an eco-friendly artist collective speaking with the founder about the inspiration behind her creation. I was expecting time in classrooms with lectures on how different crafts were made, not time in the forest with discussions about our own connections to nature.

With rising mass production, many traditional Japanese crafts such as urushi lacquer (the Japanese art of lacquering wood), are fading, and the skills passed down for generations are slowly disappearing. Simultaneously, Japan faces increasing threats of global warming including rising sea levels, stronger typhoons, and increases in heavy precipitation, each a danger with potentially deadly consequences.

To many, the increase of climate disasters and decrease of traditional arts engagement might seem overwhelming. But Sachiko saw an opportunity to create a community in Keihoku, a city just outside of Kyoto known for its art and soul. In this community material is neither wasted nor removed from the environment, but instead is part of a sustainable cycle of artistic growth. In an ecosystem of art and healthy forest maintenance, trees grow, are cut down, replanted, and used for art in the interim.

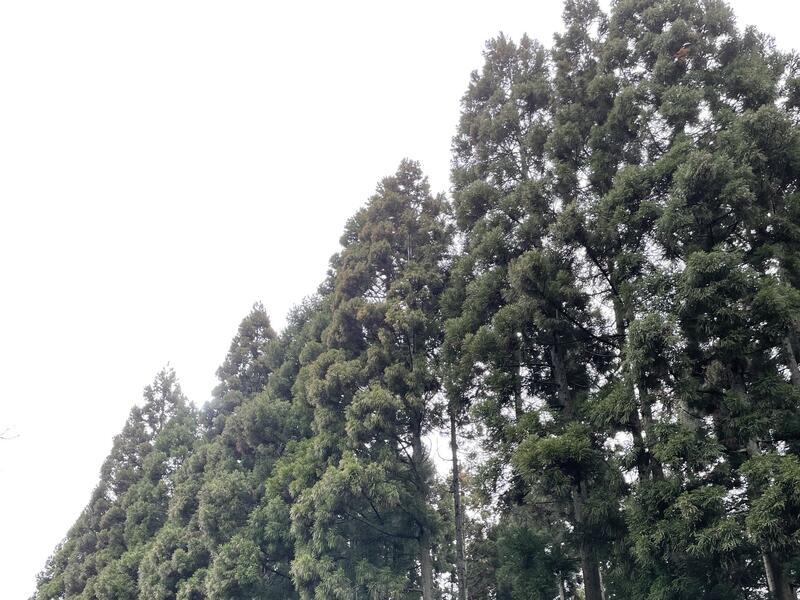

My trip to Keihoku was filled with twists and turns—quite literally—on a narrow, winding road through the mountains. Upon arrival, it was hard not to feel immense gratitude for fresh air and a respite from the hour-long bus ride from Kyoto city center. A light snow sprinkled as I met Sachiko for the tour of the Keihoku forest, adding a near-magical feeling to our exploration in the silent, towering woods.

Sachiko explained to me that Keihoku was largely a man-made forest: after World War II, the government wanted to increase cedar production for rebuilding the destroyed cities and economy. Because cedar takes such a long time to grow, the government soon stopped caring for the forest, and it fell into disrepair. Today, over 60% of the cedar in the forest in Keihoku is from this government-led initiative.

Though beautiful, these towering trees have shallow roots making them prone to falling in winds. One of the efforts of Sachiko and her team of volunteers and artisans has been to cull the overgrown population of cedar and use the wood for construction. I initially bristled at this idea, since Western perspectives of global warming view any tree loss as a travesty. Sachiko pointed out that, by culling the trees, she allows the forest undergrowth to blossom and for urushi trees to thrive, which supports the Japanese art of urushi lacquer.

Urushi trees take fifteen years to grow, making them a costly upfront investment. But at the end of their lifecycle, they are harvested for lacquer, used to grow new trees, and composted back into the forest. With a decline each year of both urushi trees and urushi lacquer being produced, it is no wonder that the art of urushi lacquer, which dates back to the Jomon period roughly 9,000 years ago, is in many ways endangered. Artisans who have relied on these trees for their work have found it increasingly rare, expensive, and less relevant to the modern consumer, which is why Forest of Craft’s commitment to increase sustainability has been so important.

Unlike its plastic counterpart, urushi lacquerware can be regularly used for over 400 years. Repairing urushi crafts after damage is also simple: just brush it over and fill in the crack with more lacquer. Alternatively, urushi pieces that must be thrown out can simply be tossed to nature to biodegrade.

Takuya Tsutsumi, Sachiko’s fellow artisan and co-founder of Forest of Craft, put the sustainable properties of urushi lacquerware to use. First, Takuya contributed urushi bowls to local classrooms, seeking to end the use of disposable plastics at lunchtime. Next, Takuya designed an urushi surfboard with surfboard brand Alaia that would brave the waves sustainably. This project opened the door for a future in which plastic surfboards cease to contribute to landfill waste. He has even furthered this interest in outdoor sustainability by developing a bike and skateboard made of urushi lacquer on wood, blurring the line between the practical and the beautiful as he pursues sustainability.

Exploring Keihoku’s crafts and talking with Sachiko made me reflect on my own consumption of Jewish crafts, and empowered me to question how we can make our traditions more sustainable. While I have sourced some crafts from local artisans whose stories I take the time to know, my go-to is cheap, disposable Jewish knick-knacks. Amazon makes it all too easy and affordable to buy a 100-pack of plastic dreidels for $20. But that cheapness doesn’t account for how many of those items then occupy landfills in the very nature that we as Jews are taught to protect. Seeing Forest of Craft in action made me question ways that ancient Jewish artforms could be improved upon to become more sustainable in ways that align with Jewish values. Take, for example, the concept tikkun olam which calls on Jews to quite literally “repair the world.” From the perspective of climate change means this healing the damage we have wrought.

Deuteronomy 20:19-20 instructs us that even when waging war, we “must not destroy [a city’s] trees,” yet it is easy to overlook that instruction when organizing events or making purchases for ourselves. Even many artisanal dreidels/mezuzot are not sustainably made and sourced. It is the connection between buyer, creator, and nature that makes Forest of Craft such a special place, and that should spread to Jewish crafts and consumption habits as well. Like Sachiko, we must work to ensure that traditional crafts, while cherished, are also sustainably made, providing artisans with the chance to hone their skills in a new way, and pushing us all to develop a greater connection with nature. This Tu B'Shvat we must question and push ourselves to be better, as is central to Judaism, and just as Sachiko did in the creation of Forest of Craft. Traditions are beautiful, but so is adaptation, change, and cherishing our environment.