Turning Toward Myself and My ADHD

The original version of this piece appeared in New Voices magazine.

I have always been ashamed of having ADHD. There has never been a moment that I have really felt smart, capable, or enough; it feels like I’m in a race I’ll never finish, desperately trying to catch up with everyone around me.

The minute I notice a marker of my ADHD, I try to stifle it. I learned at a young age not to make jazz hands in front of other people, make silly sounds with my mouth so I could focus better, or talk about my imaginary friends and stories. In fourth grade, I stuck a piece of fuzzy Velcro on my desk so I could run my fingers along it, desperately trying not to jazz-hands my way through checking my work. My hands would vibrate when I was excited, and so would my mouth. Often, I would play “cowboy hands,” wiggling my fingers while proof-reading as if I was about to reach for my holster. It helped me focus.

When I wanted to calm myself down, I made repetitive motions or sounds. When I got to high school and my medication dosage was upped, I developed painful tics that I couldn’t suppress, factoring into a desire to socially isolate. It turns out that this behavior is called stimming. Stimming, or self-stimulation, is used by everyone to self-regulate when the body becomes overwhelmed by any emotion.

I never want to think about or remember having ADHD, because it feels like remembering all of my shortcomings. When I see my friends being open about having ADHD or being autistic, I feel both jealous and fearful. These days, liking everything from slime to fidget spinners to ASMR is normalized. What’s wrong with me? Why can’t I be okay with myself?

When I’m alone at home, I often notice myself talking. Not baby talk to my cats, just making beatboxing sounds, repeating words or phrases, or making up little songs. They feel good and they’re fun to do. I avoid making jazz hands while I read over work, so instead, I chew on my nails and the inside of my cheeks until they bleed. I pace. I shake my leg until my father yells at me to stop. I tap. I crack my knuckles. I still feel restless. After learning new Arabic, Turkish, or Hebrew words, I enjoy just repeating the words out loud. I cringe when I see Jews rocking back and forth during the Amidah. I wince when I see Muslims engage in dhikr, repeating and swaying. I hate them, and I want to be like them. I’m jealous, and I’m afraid.

Seeing it helps, though. No one can tell me what God is, only what They is not. So maybe, when I am excited by everything around me, things I feel are en sof, without end, like God, I fidget and make noise. I see these parallels in my personal life, but also in the work of Sephardic kabbalistic musician Victoria Hanna.

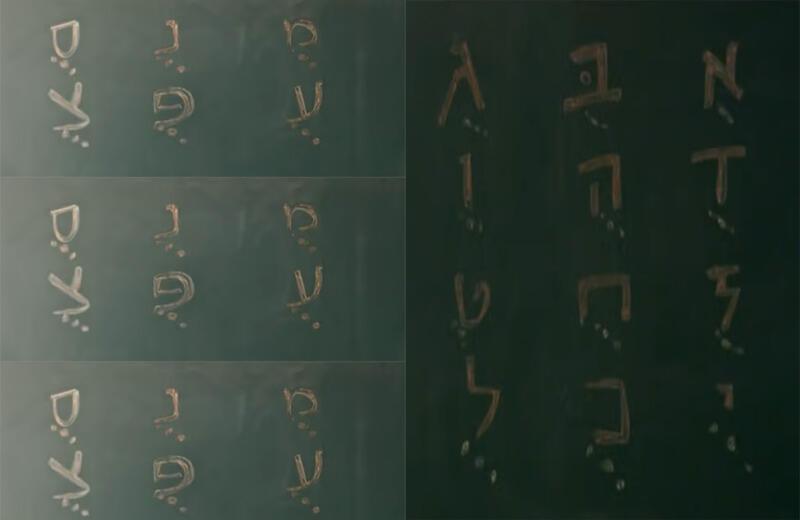

Hanna was born and raised in an Orthodox, Egyptian, and Persian Jewish family. Her breakout hit was her song “Alef Bet,” in which she recites the Hebrew alphabet with influences of traditional Sephardic pronunciation. Hanna is a weird girl, and I feel like she maybe sees weird me. She plays with her mouth in the music video, stretching it wide and closing it, playing with her hands, too. The letters on the page and on the chalkboard move with her. She’s seeing them the way I see them when I read and re-read. I can repeat after her. She’s loud enough to drown out all the little voices from my childhood telling me I’m retarded, and that to have ADHD or to be autistic is bad.

In “Ani Yeshena,” Hanna snaps,

“Qol dodi do

Qol dodi do

Qol dodi do feq-eq-eq-eq.”

She’s experiencing and sharing the pleasure of how a sound feels in her mouth. She’s teaching me how to feel the same way.

Listening to Hanna requires other unlearning as well. She sings with the same nasal quality as many Balkan Muslim traditional singers who are women. She uses quarter tones, which, in a Western-European musical tradition, are considered out of tune. People pay Hanna to teach them how to experience Hebrew her way: an incredibly embodied way. She presents a chart of the traditional associations between Hebrew letters and the body in her video “22 Letters.” It’s the positive stimulus not just of performance, but of getting to play with what you say, that I have so often denied myself.

Another female singer who teaches this to me is the late Fatima Kuinova, a Bukharian Jewish singer. When I first listened to her music in depth, I flinched at the highly dramatic, wavering quality of her voice, which rushed against my ears like a sparkling wave. To a friend, I described her voice as sounding like someone excitedly ripping fabric. To all of the things I had learned in my American musical education, Kuinova and Hanna said, “I love this, but I also love what doesn’t fall within its scope.” And their music wouldn’t be the same, not nearly what it is, if they didn’t play with their voices and hands.

When I sing along with Kuinova’s “Bijo Jak,” a Judeo-Tajik wedding song, I also play with how much my voice has breath and breaking; I love imitating the phonemes, making my g sharper and my kh soft. Victoria Hanna’s wispy het and delicate, clicking qof remind me that the Hebrew I learned— extracted from Arabic—is not only normal, but beautiful. In the words of Ella Shohat (in a speech on the plenary panel of the Women’s Conference in 1994, given alongside Mira Eliezer and Tikva Levy):

Growing up, we ordered our mothers to be quiet. In an attempt to climb the social ladder, we forbade them from speaking Arabic, Persian, Turkish, or Hindi. We pleaded with them to work on that Moroccan, Iraqi, or Yemenite accent of theirs when speaking Hebrew. We begged them to start being Israelis—in other words, Ashkenazi. Consider the fact that we, the girls, used our verbal power to censor and silence our mothers. I see our struggle as Mizrahi feminists beginning first and foremost with our attempt to overcome external silencing mechanisms and our own self-silencing.

It reminds me that children of immigrants—like me—so often do not receive either the help we need or the care we deserve for things like ADHD, which is just as much an emotional processing disorder as it is something that affects my ability to structure my life. Our behavior marks us as problem-children, troubled-children, and even if we get help, our behavior is still pathologized, linked to our cultural background, and not looked at for what it is. I won’t silence myself; I’ll keep learning my Arabic, Hebrew, Albanian, and Turkish; I’ll stop begging myself to be something other than what I am, in every aspect of my life.

This journey began with watching my wider religious affiliations engage in self-stimulation, embodied regulation and expression of their relationships with God, and realizing that I had developed a circle of friends who were open about their ADHD and autistic-ness. I hope that I can turn toward them to turn to myself—to continue healing by drawing on centuries of precedented, precious sound.