Art: Representation of Biblical Women

For centuries, art has portrayed biblical women in ways that reflect society’s attitudes towards women and their role. Depictions of female biblical figures fluctuate according to historical and social perceptions. Delilah, Potiphar’s wife, and Judith are especially valued in Northern culture, where they express the theme of woman’s domination. Other figures, such as Jael, Esther, and Judith, become types in Christian reception and are therefore popular and admired female models. The moralistic medieval visualization of Lot’s daughters, Bathsheba, and Susanna became highly erotic during the Renaissance and Baroque periods. Jewish art often features heroic and worthy women who, through their courageous deeds, helped to triumph over Israel’s enemies. Hagar and Rachel are often invoked by Israeli artists to convey their attitude towards the Jewish-Arab conflict.

Introduction

In narratives or abridged cycles more or less faithful to the biblical text, art has portrayed biblical women as role models and reference, occasionally adding exegetical elements both Christian and Jewish. Although the text of the Bible became fixed at different dates and in various versions, these images are not fixed, but reflect the ebb and flow in society’s attitudes towards women and their role.

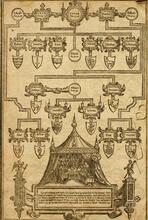

In early Christian and medieval art, the image of biblical women served primarily to emphasize a typological meaning. In the late medieval age, their images are conjured up in such highly Christian moralistic scriptures as the thirteenth-century Bibles Moralisées, which alternate biblical stories with commentaries devised by Parisian theologians, and the 1400–1530s manuscripts of the Speculum Humanae Salvationis, in which the illustrations, while often devoted to the significance of the prefiguration, distort certain events at the expense of the biblical account. The courageous acts of Jael, Judith, and Esther intended to save their people, or the figures of Miriam and Ruth based on the woman of worth (Prov. 31:10), are recurrent features in this and later art. With the introduction of print, sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Northern artists produce books presenting the images of biblical women such as Sarah, Rebecca, and Rachel as paragons of virtue. One such book is the illustrated poem by Hans Sachs, written in 1530, Den ehren-spiegel der zwölf durchleuchtigen frauwen dess alten testaments.

Renaissance, Baroque, and eighteenth-century art often have recourse to biblical women as an acceptable excuse for presenting the contemporary ideal of the female sensuous nude. Figures such as the Daughters of Lot, Bathsheba, and Susanna are repeatedly portrayed. During the nineteenth century the “good” biblical wife tends to be eclipsed by the “evil” one. A case in point is Delilah, who reaches her peak as the image of the femme fatale, deadly seducer of men, in fin-de-siècle art. Twentieth-century art sees the emergence of a secular image of the biblical women, which replaces the misogynist view of earlier centuries, treating them from formal, personal, or national perspectives.

The oft-cited prohibition of the second commandment did not prevent the creation of Jewish images. The third-century wall paintings in the Dura-Europus synagogue through the Hebrew illuminated manuscripts confirm the truth of this statement. The Biblical women, commonly portrayed in relation to various festivals, are construed as courageous heroines helping their people. The advent of Zionism and the awakening awareness of the Jewish people to their national identity led Jewish and Israeli artists to perceive the illumination of the Bible as a way either to express their identification with the ancient national independence or to tackle the Israeli-Arab conflict.

Islamic art portrays usually only a few biblical episodes related to women such as Adam and Eve or Joseph and Zuleika. Muslim artists who created them were probably influenced by Christian tradition, especially that of the Eastern churches in the area.

Seductive

Eve

Genesis 2–3 recounts the creation of man and the origins of evil and death; Eve, the temptress who disobeys God’s commandment, is probably the most widely discussed and portrayed figure. Traditional Early Christian funerary iconography shows Adam and Eve standing on both sides of the snake-entwined tree of knowledge, hiding their private parts with leaves, as for example on the sarcophagus of Junius Bassus (359, Vatican St. Peter’s Treasury). This image conveys a typological-redeeming message according to which the Divine grace lost to humanity will be bestowed upon the faithful after their death. The eleventh-to thirteenth-century Byzantine Octateuchs—densely and lavishly illustrated Bibles comprising the Pentateuch, Book of Joshua, Book of Judges, and Book of Ruth and augmented by early patristic commentaries— in turn present a narrative cycle illustrating the creation of Eve, the sin, God’s reprimand, the divine curse, the Expulsion and the couple’s tasks. Influenced by Christian exegesis which interprets her both as a type of Church and Mary and as mother of humankind, these illustrations present the figure of Eve in a favorable light. However, the portrayal of Eve in Western medieval art is different. While the Carolingian Bibles depict Adam and Eve alike, implying their even share of responsibility to the Fall, as for example in the Moutier-Grandval Bible (840–843), later artists adopt an increasingly misogynist approach: Eve is constantly coupled with the Devil and juxtaposed with the sacred figure of Mary. This approach originates in the sayings of Augustine (354–430), who sees Eve’s sexuality as the destructive tool of male rationality; henceforth she becomes the archetype for all females. Representative of the influential Augustinian attitude is the typological program presented on the sculpted bronze doors of St Michael’s Cathedral, Hildesheim (c. 1015). In the scene of the Fall, for example, the fruit in the snake’s mouth matches the apple-like form of the woman’s breast, a blunt reference to Eve’s use of sexuality to tempt Adam into disobedience. In the scene of God admonishing the sinners the snake placed between Eve’s legs takes on the form of a dragon (Satan), conveying the association of Eve’s sexuality-Satan-Fall. The vituperative rendering of Eve persists throughout late medieval art. The artist of an undated Speculum humanae salvationis replaces the figure of Adam in the Fall with a female-headed basilisk, an imaginary creature interpreted by Christian popular thinking as one of the guises adopted by Satan. Numerous medieval works of art depicting the Creation cycle in all media—frescoes, mosaics and vitrages—are intended to function as a prefiguration of the events to take place in the New Testament; e.g., the creation of Eve was understood as prefiguring the birth of the Church (Ecclesia). Thus, in a Parisian Bible Moralisée (c.1240), Eve, helped by God-Christ, leaps from the side of sleeping Adam. Above this scene is depicted the Crucifixion, with a crowned Ecclesia emerging from the wounded right side of Christ.

Sixteenth-century artists, influenced by Northern theology which considers woman as evil and tempting, continue to dwell on Eve’s carnal nature as an explanation for Adam’s unreasoning capitulation. This perception is amply illustrated in the left panel of a diptych made by Hugo van der Goes (d. 1482) in ca. 1470 where Eve, her body slightly turned towards Adam, plucks the fruit without the help of the woman-like snake. The moralizing attitude persists in seventeenth-century Dutch art. In his etching Adam and Eve (1638), Rembrandt (1606–1669) shows the first couple, relatively adult, at the moment of temptation: on the tree lurks the dragon/snake, emphasizing his satanic nature. The similar roundness of the apple form and the round swell of Eve’s belly point to the link between the two; it was as a result of eating this fruit that the fruit of the womb of all women would forever be brought forth in pain. A different interpretation, viewing the Fall as a male-female struggle, emerges in this era. Adam is featured as the subordinate figure while Eve assumes a dominant position, as exemplified in the painting by Tintoretto (1518–1594), The Temptation of Adam and Eve (1550).

Unperturbed by this misogynist perception of Eve, the German and Netherlandish art of the sixteenth-seventeenth century considers her—along with a constant canon of virtuous women such as Sarah, Rebecca, Esther, and Judith—as a didactic tool in the moral education of women. A telling example are two closely related series of prints entitled Icones illustrium feminarum veteris testamenti made by Maarten de Vos (1532–1603) around 1590/95, depicting thirty-five women of the Old and New Testaments. The inscription accompanying the figure of Eve describes her as the first wife and mother, although the print shows her rather as the prototype of the diligent housewife, with spindle and distaff, vegetables, and a burning fire.

The perception of Adam and Eve changes in the eighteenth century, mainly under the influence of John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), which emphasizes the man’s free choice and his honor and exalts Eve’s beauty. From now on there emerges a secular image of Eve, transmitted in modern art mainly through her transformation into a femme fatale—a compound of beauty, seductiveness and independence set to destroy the man. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s (1828–1882) painting of Lady Lilith (1864–1868, repainted 1872–1873) epitomizes this approach. The beautiful and melancholy woman combing her amazingly luxurious hair is no longer Adam’s first wife—the midrashic devil—but rather a woman of flesh and blood.

Formal problems, preoccupying many modern artists, can be discerned in the sculpture Adam and Eve (1916–1921) by Constantin Brancusi (1876–1957). The first couple is conceived as two almost equivalent figurative components fused into a whole composed of a series of geometric forms—Adam represented in the lower part by angular forms; Eve represented in the upper part by an interplay of curves.

The iconography of Adam and Eve is developed from the thirteenth century on in Creation cycles illuminating The "guide" to the Passover seder containing the Biblical and Talmudic texts read at the seder, as well as its traditional regimen of ritual performances.Haggadot, Bibles and other Hebrew manuscripts, attesting to the influence of Christian art. Thus for example the Creation of Eve in the Sarajevo The "guide" to the Passover seder containing the Biblical and Talmudic texts read at the seder, as well as its traditional regimen of ritual performances.Haggadah (Barcelona [?], fourteenth century) follows the identical Christian portrayal patterns in contemporary illustration—Eve is emerging from the side of the sleeping Adam.

The interchange between Christian and Jewish illustration of the Creation cycle persists in the seventeenth-eighteenth–century Ze’enah u-Re’enah, popular versions of the Bible incorporating Midrashim, which were intended for women. Although the artists illuminating these books faithfully copy the Christian Bible, they alter or omit depictions unacceptable in a Jewish version. Thus the God-Creator of a Lutheran Bible (Frankfurt-am-Main, 1662) is replaced by a black spot in the printed Jewish version of Ze’enah u-Re’enah (Sulzbach, 1692). Yet the integration of Christian elements into the eighteenth-century versions of these books may reflect the assimilatory process undergone by Jews, especially in Germany.

The artists of the early Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts (1906–1929) perceived the illumination of the Bible as a way to express their identification with ancient Jewish national independence. This approach is exemplified in the highly romantic, exotic rendering of Eve recurrent in Abel Pann’s art (1883–1963). In his In the Garden of Eden (1920s) the naked couple walks serenely beneath the trees and among animals in a tropical landscape, heavily ornamented in the Jugendstil style.

Most noteworthy is the approach of Marc Chagall (1887–1985), who incorporates both Christian and midrashic exegesis in the representation of the first couple. Thus for example the drawing Paradise: The Tree of Knowledge for Verve Bible II, 1960, depicts Adam and Eve lying on the ground, the Tree of Knowledge springing from their fused figures into one whole. The unusual iconography relates to the Christian theology associating the Tree of Knowledge with the mystical tree used to make Christ’s cross, known as the Tree of Life. In the painting Adam and Eve (Hommage à Apollinaire) from 1911–1912, the androgynous couple (Gen. 1: 27) is encircled by a giant clock pointing to nine, according to the A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).Midrash the hour at which they sinned.

Islamic art illustrates mainly the Expulsion of Adam and Eve, driven out of the Garden by an angel or a guard. The Muslim artists incorporated in the otherwise traditional iconography a peacock, symbol of both carnal needs and man’s spiritual desire for individuality in Sufi thought, as for example in an illustration to The Garden of the Happy by Fuduli (Turkey, eighteenth century).

Potiphar’s Wife

The wife of Potiphar fell in love with Joseph, her husband’s slave. In spite of her advances, Joseph refused to yield to her. One day, when nobody except Potiphar’s wife and Joseph was in the house she entreated him to lie with her and seized his garment. He refused and fled. His discarded clothing was later used by the rejected woman to incriminate him (Gen. 39:1–23).

The story of the Egyptian woman sexually harassing young Joseph was immensely popular in Christian, Jewish and Islamic art. Early Christian art adopts a narrative approach to render the intricate story, incorporating extrabiblical rabbinic motifs, as in the miniature in sixth-century Vienna Genesis, a Greek paraphrase of the book of Genesis made in Constantinople. In the upper register Potiphar’s wife is grasping Joseph’s mantle while seated on a couch. The biblical account says only that Potiphar’s wife tried to seduce Joseph when nobody was in the house. However, rabbinic commentaries explain the absence of Potiphar’s people by referring to a festival when all had gone off to the temple; Potiphar’s wife feigned illness, hence the presence of the bed. The biblical episodes depicted in many medieval works were enlarged by the addition of apocryphal ones, as for example in a Parisian Bible moralisée dated 1215–1230 where Potiphar’s men are shown beating Joseph, an incident derived from Jewish legend. The moralizing commentary accompanying the miniature associates the figure of Potiphar’s wife with the evil serpent/alias Synagoga, whereas Joseph represents Jesus Christ falsely accused before Pilate. Consequently, the men beating Joseph are the Jews whipping Christ and preparing to crucify him.

In early Renaissance art Potiphar’s wife comes to symbolize Luxuria (lust), as exemplified in a fresco painted by Roberto d’Oderisio (active fourteenth century) in Sta Maria Incoronata, Naples (c. 1340–1343). Seated on her bed, she raises her dress to reveal her legs, while the frightened Joseph flees through her chamber door. Following Luther’s commentary on the attempted seduction—interpreting the wife’s misconduct as a threat to her marriage and her disgraceful actions as conduct applying in general to all women—Northern works of art relating to this subject abound. Lucas van Leyden (1494–1533) produced a series of engravings including Joseph Escaping Potiphar’s Wife, 1512. Potiphar’s wife, who grabs forcefully at Joseph’s mantle while he tries to escape through the door of her room, is a reversed version of the commandment forbidding coveting one’s neighbor’s wife. Rembrandt (1660–1669), in his turn, dwells on the erotic missed encounter in a very explicit way. In his etching Josef and Potiphar’s wife (1634), the woman’s body, naked from the waist down, is twisted in order to be able to grasp at Joseph’s garment; her parted legs leave absolutely no doubt as to her sexual intentions.

Unlike Christian art, Potiphar’s wife is rarely illustrated in medieval Hebrew manuscripts, all of which show the woman in bed. Probably the existence of a common Jewish archetype transmitted to the Jewish world through the Byzantine world, as explained above, is the reason for this iconography (Golden The "guide" to the Passover seder containing the Biblical and Talmudic texts read at the seder, as well as its traditional regimen of ritual performances.Haggadah, Barcelona, c. 1320). By the early sixteenth century, as in the moralistic Northern iconography, Potiphar’s wife became the standard subject for illustrations of the commandment “Thou shalt not commit adultery” in Hebrew illuminated manuscripts, embodying the concept of adultery.

One of the rare depictions in Israeli art is Abel Pann’s drawing Potiphar’s Wife (1945), where the image of the young, exotic woman, reclining in a suggestive manner, is influenced by contemporary films and the femme fatale iconography.

The Koran dedicates to Joseph a full Sura (ch. 12). Joseph’s refusal to yield to the advances of Potiphar’s wife (later called Zuleika) is interpreted in Muslim commentaries as a confrontation between two religions, Joseph symbolizing the prophet of God, Zuleika paganism. In the allegorical poem Joseph and Zuleika by the Sufi sheikh Jami (fifteenth century), the woman’s obsessive love represents that of a Sufi for his Creator. This perception led to an iconography diverging from the Christian one: Zuleika does not seduce Joseph but kneels down before him in supplication, grasping his robe. Moreover, their story concludes with the couple’s marriage after Zuleika destroys her idols (Joseph and Zuleika, Iran, sixteenth century); or Zuleika, grieved by the death of Joseph, puts out her eyes (Joseph and Zuleika, India, eighteenth century).

Samson and Delilah

In contrast to Potiphar’s wife, who attempts to seduce Joseph for her own pleasure, Delilah is a treacherous seductress who sells Samson to the Philistines for money (Judges 16: 4–20). In the field of typology the story of Samson’s emasculation at the hands of a woman is extremely popular from medieval times onwards: Samson parallels Christ, whose death is not the end but the beginning of man’s redemption; and the love Samson bore for the Philistine woman was interpreted as Christ’s love for the Church. Since the story of Samson, who primarily indulges his sexual drives, harmonizes with the Christian attitudes toward sensual pleasures, it becomes a useful didactic tool in the hands of the Church, warning against woman and her duplicitous nature. This attitude is reflected in the Bible Moralisée (c. 1215–1230), where the figure of Delilah cutting Samson’s locks signifies the flesh putting the soul (Samson) to sleep through covetousness and gluttony, later putting it in the devil’s hands.

The didactic attitude prevails in some of the Renaissance works of art, as for example in the woodcut by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) done for Der Ritter vom Turn von den Exemplen der Gottsforcht und Erberkeit (Basle 1493), a book written more than a century earlier by Geoffroy de la Tour Landry for the moral instruction of his daughter. The text draws a parallel between Delilah’s mercenary treachery and Judas’s betrayal of Christ. The illustration represents Samson lying on the lap of Delilah while she cuts his hair; meanwhile, two men conversing contemplate the couple from a window. Their commentaries are surely intended to hint at the dangers of woman in general, thus transforming the figure of Delilah into a universal example of woman depriving man of his strength. The seventeenth-century iconography of Delilah places the treacherous scene in a brothel-like setting and associates it by extension with venality and lasciviousness, as in Samson and Delilah (1608) by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640). The scene takes place at night; Samson’s body is resting in Delilah’s lap. The erotic atmosphere of the place is enhanced by the principal protagonists, partially clothed.

In the nineteenth century Delilah embodies the idea of femme fatale and is frequently associated with the devastating figure of Salome, who incited the martyrdom of John the Baptist. This subject greatly interested Gustave Moreau (1826–1898), who treated it frequently. In his Samson and Delilah (1881–1882) Samson, renowned for his Herculean strength, is represented as an androgynous ephebe prostrate on Delilah’s lap. Delilah’s impassive expression as she proceeds to her treacherous act betrays her true feelings; she is not a woman deriving pleasure from the sexual encounter, but one who is scheming against her lover, the very essence of the cruel and perverse femme fatale.

Judith

Judith, the pious widow from Bethulia who sets out with her servant for the tent of the Assyrian general Holofernes, chops off his head with his own sword, escapes with her servant and subsequently helps the Israelites to victory over the Assyrians (Judith, chs. 10–13), is one of the very few biblical women who could be identified both with the traditional Catholic version of the Virgin Mary and with her counterpart, the sexualized seductress Eve.

It is in her embodiment as the sexualized woman that Judith appears in sixteenth-century Northern art, whose focus is on those elements of the story that outline her cunning in using her feminine charms and her deadly art of seduction. As such she is equated with evil women like Delilah. The artists frequently expose her as an aggressive, seductive and licentious sinful figure, impassive in her act, as for example in Judith (1525) by Hans Baldung Grien (1484/5–1545).

The Renaissance and Baroque iconography of Judith implies that she slept with Holofernes before killing him, contradicting the biblical text, where the pious Judith entices the Assyrian general with her clever words and her beauty, yet remains untouched by him. The demotion of Judith, envisaged as an immoral woman who killed her lover, is probably due to the confusion between her virtuous figure and that of Salome. Hence the works of art associating the sexual act with the murder, characterized by a somewhat personal tone. Thus Cristofano Allori (1535–1607) identifies himself in the features of Holofernes and in those of Judith a girl known as La Mazzafirra, with whom he was hopelessly in love (Judith with the Head of Holofernes, 1610–1612). Judith’s swinging the severed head of Holofernes adds a pitiless touch to the incongruous scene. Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1652/3) in her turn presents a remote self-portrait in the figure of Judith; yet she is clearly identifiable in the features of Abra, Judith’s servant, traditionally portrayed as a passive witness, who functions here as a supportive aide-de-camp (1612–1613). The cruel attack of both women on Holofernes may express the artist’s wish to take revenge for her own rape.

The portrayal of Judith as a woman betraying her lover, bringing about his perdition, is a theme of choice in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Gustav Klimt (1862–1918) approaches the subject in two paintings, Judith I (1901) and Judith II (1909). Bare-breasted, Judith is depicted as a sensual, erotic woman, bearing on her face an expression of sexual ecstasy, emphasized by her dimmed eyes and half-open mouth. Both images make of her the quintessence of the femme fatale, while the use of gold turns her figure into an icon of this universal theme.

Heroic

Jael and Sisera

Sisera, a military commander and enemy of Israel, sought refuge during an attack in the tent of Jael. Jael welcomed him, gave him refreshment, and induced him to sleep while she stood guard. As he slept she drove a tent peg through his head (Judges 4:17–21).

Medieval art frequently represents Jael, as for example in a woodcut Speculum humanae salvationis (ca. 1360). The moralizing text which accompanies the illustration upholds her as a defender of Israel, associating her act with the Virgin’s triumph over the devil.

The works of Christine of Pisan (c. 1365–c. 1430) initiated a literary debate which came to be known as the querelle des femmes—the debate about women. The theme, extremely popular in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, was portrayed through the cycles entitled femmes fortes, as exemplified in the engraving by Hans Burgkmair the Elder (1473–1531) conceived as a cycle of nine “women worthies” comprising three good pagans, three good Jews (Esther, Judith and Jael), and three good Christians, paralleled to a comparable cycle of male heroes (ca. 1519).

The perception of Jael as a courageous woman continues in Dutch art, where she may be associated with Deborah, whose fame emerges from her role as a military leader. Salomon de Bray (1597–1664) makes her solitary act even more outstanding than the military actions of Deborah and her general, Barak (Jael, Deborah, and Barak, 1635). Jael’s monumental figure—overshadowing those of Deborah and Barak—looks directly at the spectator. Holding the tent peg and the hammer, her heroic weapons, she gazes intently, her face bespeaking an unwavering resolution.

Esther

Esther became the second wife of King Ahasuerus of Persia. Her story is intertwined with the unsuccessful attempt of the evil Haman, Ahasuerus’s minister, to kill the Jews. The threat was averted by the courage and shrewdness of Esther and her cousin Mordecai. Medieval thought interpreted Esther’s story as a typological parallel for the Virgin as intercessor before God.

Although one might consider Esther’s concealment of her origins as a form of deception, she becomes a model of virtuous married women in fifteenth-century Italy, shown in cassone, marriage chest, paintings and other furnishings that were customarily commissioned for the homes of newlyweds. A telling example is the narrative cycle painted on a cassone, attributed to Filippino Lippi (1457–1504), probably commissioned by wealthy Florentine Jews. Here and in other works of art, as for example in Esther Before Ahasuerus, an engraving by Lucas van Leyden (1518), the heroine is depicted kneeling before Ahasuerus; Ahasuerus takes his gold scepter, lays it upon her and bids her speak. Tintoretto revolutionizes this formula in his painting of ca. 1547–1548: Esther faints before Ahasuerus, while the king extends the pardoning scepter. The portrayal of Esther in an act of archetypal feminine weakness, taken up by most Baroque artists, is based on the apocryphal text (Esther 15: 7–11), accepted as a deuterocanonical one at the Council of Trent (1545–1547). Yet the reason for the appearance of this particular motif in Italian art, where Esther’s posture implies her autonomy vis-à-vis the king, is to be sought in an ever-growing economic and cultural autonomy of women, occurring especially in Venice and Bologna.

The knowledge of Jewish history regarded as necessary to the understanding of Christianity in Dutch culture revives the subject. Jan Steen (1625/6–1679) locates the banquet scene given by Esther, and its dramatic rendering, in a Dutch interior where all the protagonists are clad in contemporary clothes (The Wrath of Ahasuerus, c. 1660). The painting expresses the parallels between Esther’s triumph over Haman and the successful Dutch uprising against Spanish domination.

The nineteenth-century romantic view and the fascination which the Orient and its exoticism held for European artists are present in Esther Prepares Herself for Ahasuerus (1841) by Théodore Chassériau (1819–1856). Depicted against a pastel colored sunset, his Esther, an Oriental odalisque, is preparing to receive her master’s visit. The beautiful half-nude woman is assisted by two exotic Oriental maidservants.

The basis for the festival of Holiday held on the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar (on the 15th day in Jerusalem) to commemorate the deliverance of the Jewish people in the Persian empire from a plot to eradicate them.Purim, the story of Esther has been read aloud in the synagogue since antiquity. Hence it was illustrated in a number of Jewish festival prayerbooks (Miscellany, France, c. 1280). From the sixteenth century on, illustrations of Esther, enriched with additional scenes and lavishly ornamented, were incorporated into the Scroll of Esther.

Judith

In its Catholic counterpart, Judith becomes an allegory of the victory of purity over vice and thus a prefiguration of Mary overcoming Satan. This popular belief is expressed in a miniature in a Flemish Miroir de l’humaine Salvation (c. 1500) depicting Judith murdering Holofernes, whose Latin inscription reads: “Judith Decapitates Holofernes.” The scene makes a pendant with the adjacent scene depicting the Virgin seated reading in an interior. Here the Latin caption reads: “Maria Conquers the Devil.” Judith is also represented treading on Holofernes instead of beheading him, thus associating her with the triumph of Humilitas—considered the source of all virtues—originating in the Church, over the vice of Luxuria, deriving from Satan (Holofernes).

The medieval analogy between David, the weak shepherd who overcame the strong Goliath, and Judith, who vanquished the vainglorious Holofernes, appealed especially to Renaissance artists, who drew a parallel between the two figures in their works of art. A most eloquent version of this perception is the sculpture Judith (1455–1457) by Donatello (1386–1466). The female figure raising her sword high as she is about to sever the head of Holofernes, who kneels before her, was associated by contemporaries with Donatello’s bronze statue of David with Goliath’s head at his feet, made about thirty years earlier. Yet the Italian artist not only alludes to the moralistic medieval conception of Judith, but also casts her in the role of an allegory of civic virtue. Upon the exile of the Medicis from Florence, both statues were confiscated and set in front of the City Hall, the Palazzo della Signoria, where they came to be seen by contemporary Florentines as the embodiment of civic patriotism—symbol of their struggle for freedom and independence and their victory over their foes and oppressors.

Although not part of the Hebrew Bible, the apocryphal Book of Judith was very popular in Jewish culture and frequently illustrated in art. Drawing on the association of the story of Judith with the Lit. "dedication." The 8-day "Festival of Lights" celebrated beginning on the 25th day of the Hebrew month of Kislev to commemorate the victory of the Jews over the Seleucid army in 164 B.C.E., the re-purification of the Temple and the miraculous eight days the Temple candelabrum remained lit from one cruse of undefiled oil which would have been enough to keep it burning for only one day.Hanukkah feast and the Hebrew liturgical poempiyyut (devotional poetry) recited during the feast, in which she is described as belonging to the Hasmonean family, she is portrayed in the company of famous characters celebrated during Hanukkah. As in Christian iconography, she is depicted in a heroic posture; in one hand the dagger, in the other hand the decapitated bloody head of Holofernes, as illustrated in the Rothschild Miscellany (Ferrara[?], 1470–1480); or on a silver Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah breastplate from the Meisl Synagogue, Prague (1708), where she is associated with the High Priest, whose task was to light the Temple menorah.

The (Male) Gaze

Daughters of Lot

Convinced that the human race was annihilated by the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, the daughters of Lot trick their father into sleeping with them (Gen. 19:30–38). Early Christian fathers sympathize with the incestuous act, seeing the daughters’ behavior as a necessity to perpetuate the human race. Hence, their offspring, Moab and Ammon, are understood as forefathers of the Jewish people. The Byzantine Octateuchs depict this perception in two scenes: the eldest daughter is giving birth to her son, Ben-Ammi, while the younger daughter puts the infant to sleep. Western theological texts, such as Historia Scolastica by Peter Comestor (d. c. 1179), tend to condemn the daughters’ behavior and see them as symbols of the flesh and the devil. The acrimonious attitude is eloquently illustrated in the thirteenth-century moralized Bibles, portraying the young women with the loose hair and clinging dresses of whores as they offer wine to their father in his bedchamber.

The moralizing perception persists in Northern European art where the emphatically erotic scene epitomizes the idea that lust is the obvious source of man’s downfall. A telling example is Lucas van Leyden’s engraving Lot and his Daughters (1530); Lot and one of his seductive, voluptuous daughters are engaged in a fervid embrace, while the other daughter pours more wine into the cup which the first is holding. Italian Renaissance artists, who dwell less on the moral lesson, place the protagonists in a vast landscape, shifting the focus from the erotic elements of the story to the delightful, serene mood of the landscape, as featured in Tintoretto’s Lot and His Daughters (1558–1568). Yet the Baroque again delights in the erotic aspect of the story, as exemplified in Bernardo Cavallino (1616–c. 1656), Lot and His Daughters (c. 1650), where the frivolous young women grin foolishly. An exception is the painting attributed to Artemisia Gentileschi (1640 [?]). The solemn quietude of the monumental figures and the intent look of the daughters bespeak the necessity to carry out the unspeakable act about to take place, transforming it into a ceremony, less than a seduction.

Bathsheba

According to scripture David observed Bathsheba bathing from the roof of his palace and was smitten by her beauty. He had her brought to him and lay with her. Learning soon afterward that she was pregnant, the king plotted successfully to have Bathsheba’s husband killed in battle and then made her his wife (2 Sam. 11: 2–19).

The biblical story was understood in Christian thought as the mystical marriage of Church and Christ, and Bathsheba’s bath as a type of baptism. This perception is frequently presented in medieval art. A miniature of the ninth-century Byzantine Sacra Parallela, a moralizing compilation listing numerous terms in alphabetical order, with comments from biblical and patristic sources, illustrates the scene in an interior. Bathsheba naked, assisted by a maidservant, is about to take her bath; David looks at her from an upper part of the building. The Christian commentary on the scene expresses the idea that the faithful should direct his gaze at spiritual things (God) and not toward earthly ones (Bathsheba). However, medieval art frequently links David’s sin with Nathan’s admonishment and the king’s penance, illustrating Psalm 50 (51), the penitence psalm par excellence, frequently cited in Christian liturgy. A miniature in the Utrecht Psalter (Reims, c. 820) and the ivory cover of the Psalter of Charles the Bald (842–869) depict this association and attest to its popularity.

The fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Northern artists depict Bathsheba entirely clad, sitting in the open below the palace with her feet in a pool, stream or moat, angled so as to partly face the viewer and partly David, as she features in the painting of Hans Memling (c. 1430/40–1494), Bathsheba (c. 1485). The unusual iconography may be a response to a Protestant theology that was increasingly moralist in its treatment of the Bible; or an attempt to make the Bible accessible and contemporary for lay people, depicting the then-accepted view that the best way to maintain hygiene is to wash at home rather than in bathhouses where one was most likely to become infected with disease.

Even though Erasmus (prob. 1469–1536) cites Bathsheba as an example of a Biblical subject one ought not to paint, because seeing such paintings can only lead to sin, her theme gains in popularity in Baroque art, which conceives her primarily as an objectification of the female body meant to delight the male gaze. A most telling version of this approach is Rembrandt’s portrayal of Bathsheba at Her Bath (1654). The young woman’s body is slightly twisted, as if she were in the act of turning away, and her legs are modestly crossed. She holds a letter in her hands. Here the absence of the King transforms the viewer into the spying observant, an interpretation emphasized by the palpable proximity and corporeality of the female nude.

In nineteenth-century art the figure of Bathsheba is treated in a way matching that of Salome or Delilah, a mere variation on the theme of the courtesan and lust. Usually depicted naked, without jewels or other finery, she becomes an object of desire for the male gaze, verging on the then-popular theme of the femme fatale, as expressed in one of various versions by Gustave Moreau, Bathsheba Bathing (1886–1890).

Susanna

The third apocryphal addition to the Book of Daniel (13:19–43) recounts the story of Susanna, a young woman bathing in her garden, secretly spied and lusted after by two elderly judges. They threaten to slander her if she does not succumb to their advances and, upon her refusal as a God-fearing wife, they denounce her; she is arrested and sentenced to death. It is only through the intervention of Daniel that she is saved; the elders are ultimately punished.

Early Christian Fathers interpreted the chaste and courageous figure of Susanna as an allegory of the Church and associated the Elders with the Jews and pagans who conspired against the Church. Early Christian wall-paintings and small objects feature Susanna standing in a posture of prayer between the Elders. This scene, usually accompanied by the Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace (Dan. 3) and Daniel in the Lion’s Den (Dan. 6), conveys both the Christian theme of salvation and conjugal chastity. It is in the latter sense that the cycle of Susanna and the Elders depicted on the engraved Lothar crystal is to be understood (c. 850–869). The crystal was given by the Carolingian king Lothar II (c. 835–869) as a present to his barren wife, Waldrada, whom he had accused of incest in order to divorce her and marry the mother of his children, Theutberga. Later he confessed to his false accusations and asserted his wife’s innocence and reinstalled her former rights as wife and queen.

The ideas of love and marital fidelity related to Susanna make her story a popular depiction on fifteenth-century cassoni and ivory caskets offered as gifts to newlywed women. The ever-growing interest of sixteenth-century Northern artists in the painting of landscape reverses the subject’s traditional pictorial format by making the scheming elders the center of attention and depicting Susanna in the background as a small, fully clothed figure bathing her feet in a basin, as featured in Susanna and the Elders (1526) by Albrecht Altdorfer (c. 1480–1538).

Like that of Bathsheba, the subject of Susanna became extremely popular with Renaissance and Baroque artists, for it provided a justifiable opportunity to paint a beautiful nude woman as an exemplar of chastity. She is usually depicted alone, surprised by the Elders, in a garden whose landscape elements were often the object of independent aesthetic exploration, as in Tintoretto’s Susanna and the Elders, 1555–1556. Once again it is Rembrandt, more pointedly than any other painter before him, who places the viewer in the position of a spying elder, making of the biblical subject a vehicle for the depiction of young, chaste beauty. In his 1636 Susanna and the Elders, where she enacts the Venus Pudica pose—one hand over the breast and the other over the groin—she seems to be suddenly startled by a sound behind her, although she does not see the elders, who are barely visible in the picture.

Woman of Worth

Miriam

Miriam, sister of Moses and Aaron, referred to as a prophet in Ex. 15: 20, is interpreted in Christian thought as a prototype of the Virgin Mary. Her various episodes, especially her instrumental role in Moses’s infancy (Ex. 1: 8–2: 9) and her dance (Ex. 15:20–21), are popular themes in Christian art. In early Christian funerary art she is shown playing the tambourine, closing the row of the Hebrews after the Crossing of the Red Sea. The Byzantine Octateuchs depict her in a similar iconographic formula, or accompanied by several dancing women, evoking her typological sense; she is likened to the Christian soul ascending to heaven. In the Parisian Bible Moralisées she came to be interpreted as the angelic choir praising Christ crowning his mother Mary in heaven.

Miriam’s iconography, like those of such other virtuous heroines as Ruth, Esther and Judith, is very popular in Jewish art due to the liturgical use made of the texts. She is depicted as early as 244–245 c.e. in a wall-painting in the synagogue of Dura-Europus, standing at the well that accompanies the Children of Israel in their forty years’ wandering in the desert (Num. 21: 16–18), which in Jewish legends is referred to as “Miriam’s well”. The scene of Miriam Leading the Women of Israel—Miriam standing apart drumming on the tambourine, accompanying a group of dancing women—which draws heavily on Christian art, appears also in the medieval illuminated The "guide" to the Passover seder containing the Biblical and Talmudic texts read at the seder, as well as its traditional regimen of ritual performances.Haggadah (Golden The "guide" to the Passover seder containing the Biblical and Talmudic texts read at the seder, as well as its traditional regimen of ritual performances.Haggadah, c. 1320).

Ruth

The book of Ruth recounts the story of the Moabite woman who, thanks to her loyalty to her mother-in-law Naomi and her faith in God, becomes the ancestress of David through her marriage to Boaz. In Christian patristic literature she signifies those embracing the right faith (i.e. Christianity), as opposed to the miscreant Jews, who turn away from it. The moralizing lesson is illustrated in large narrative cycles, as for example in a Parisian Bible Moralisée (c. 1215–1230), beginning with Ruth and Naomi leaving for Bethlehem from Moab, concluding with Ruth giving birth after Boaz took her for his wife. The influence of Midrashic sources can be traced in several cycles of Ruth, an example is the bag that Ruth carries in the c. 1400 Padova Bible, which is not mentioned in the biblical text.

Part of the Dutch affinity to the biblical stories was their perception that Holland was the new Israel, so that it was perfectly fitting to depict the biblical scenes in a Dutch countryside. This pastoral setting is the background for the scene where, depicted as a rich Dutch lord, Boaz instructs his servant to let the poor, humble-looking Ruth keep the sheaves of wheat she gleans (Gerbrand van der Eeckhout [1621–1676], Ruth and Boaz, 1655).

Jean-François Millet (1814–1875), who frequently depicted the rustic simplicity and labor of French peasants, was equally drawn to the landscape of the Book of Ruth—shaped by famine and plenty, planting and harvest. He subtitled his Harvesters Resting, depicting a group of peasants, Ruth and Boaz (1851–1853).

The Book of Ruth is the festival reading for Lit. "weeks." A one-day festival (two days outside Israel) held on the 6th day of the Hebrew month of Sivan (50 days, or 7 complete weeks, from the first day of Passover) to commemorate the Giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai; Pentecost; "Festival of the First Fruits"; "Festival of the Giving of the Torah"; Azeret (solemn assembly).Shavuot (Pentecost). Yet it has only a few isolated scenes in Hebrew manuscripts, as for instance the illustrated initial word panel to the Book of Ruth in the Tripartite Mahzor (Lake Constance region, c. 1322), where Ruth and Naomi are singled out with animal heads.

In the work of Jakob Steinhardt (1887–1968) the story of the righteous Moabite woman who will bring glory to Israel is used to counter the figure of Delilah, the foreigner who will bring disaster on Israel. His treatment of Ruth in the monotype Ruth and Naomi (1959) proposes a visual way of seeking an outcome for the Arab-Israel conflict.

Chaste, Obedient, and Devout

Sarah

Unable to conceive, Sarah gave her maid Hagar as a concubine to Abraham and she bore him Ishmael. When Sarah miraculously conceived after the visit of the three divine messengers and bore Isaac, she forced Abraham to banish Hagar and his firstborn, Ishmael. Repudiating Hagar, Abraham sent her into the desert with Ishmael. There, alone and in despair as her child was dying she heard the angel’s voice and in a vision was shown a water source (Gen. 16:1–21; 14–19). Medieval Christian thought sees in their figures the conflict between Christians (Sarah) and Jews (Hagar) (Gal. 4:22–31) and illuminates the idea in numerous works of art such as The Old English Hextateuch (eleventh century).

The use of biblical women, and Sarah in particular, as exponents of female virtues appears to have appealed first and foremost to the urban German and Dutch elite. It is in this role that she is cast as one of many virtuous biblical women in the series of prints, Icones illustrium feminarum veteris testamenti by Maarten de Vos (c. 1590/1595). Rembrandt adopts the same tradition and draws Sarah standing in the doorway listening to the divine messengers conversing with Abraham (Abraham Entertaining the Angels, 1656). Her figure exudes an air of positive bustle, embodying the virtues of the exemplary Dutch wife.

Jewish and Israeli art depict Sarah in various episodes. According to the A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).Midrash, Satan, disappointed that Abraham was willing to obey God and sacrifice his son, took revenge by falsely informing Sarah that Isaac had been killed by his father. Thereupon Sarah uttered three shrieks and expired (Sacrifice of Isaac and Death of Sara, Birds’ Head The "guide" to the Passover seder containing the Biblical and Talmudic texts read at the seder, as well as its traditional regimen of ritual performances.Haggadah, Germany, early fourteenth century). Unlike former artists who depict Sarah as an old woman, Abel Pann paints her as a very young exotic woman, virtually a girl (1940s), who owes her unusual iconography to the Jewish-Sephardic custom of giving daughters in marriage while they were still very young—a custom Pann encountered upon his arrival in Palestine.

“The 1948 Generation,” a term conventionally used to frame the Israeli artistic creation of the decade between 1945–1955, responded to the declaration of the State of Israel and the ensuing war with works of art whose main theme is sacrifice, generally featuring male figures. An exception is Mother of Sons (1947) by Mordechai Ardon (1896–1992), in which he tackles the horrors of the war through the colossal, anguished figure of Sarah lamenting Isaac, whose dead body lies on the altar in the foreground. Abraham is depicted as a tiny, barely discernible figure in the background. The original iconography symbolizes the sacrifice of sons for the independence of Israel and their mothers’ protest against God.

Hagar

Although she is not considered a figure endowed with virtuous female qualities like Sarah, Hagar’s poignant story is often linked to that of her mistress. She is extremely popular in sixteenth-and seventeenth-century German and Dutch art (Lucas van Leyden, Abraham Dismissing Hagar, 1508; Rembrandt, The Angel Appearing to Hagar and Ishmael in the Wilderness, early 1560s). In the modern era her theme is frequently represented, as for example in Hagar and Ishmael (1848–1849) by Jean-François Millet. The artist paints a monumental Hagar; behind her lies her emaciated son. The gigantic female figure dominating the foreground provides an overtone of dignity to her profound misery, while her hollow-eyed face makes her the epitome of anxiety. The tearful Hagar and her dying son depicted by Gustave Doré (1832–1883) are totally opposed to Millet’s restrained woman. His frantic gesticulating Hagar harmonizes well with the contemporary trend to dramatize biblical scenes (c. 1866).

The figure of Hagar banished with her son becomes an image of choice among Jewish and Israeli artists who wish to express their dilemma regarding the Israeli-Arab conflict. Jacques Lipchitz (1891–1973), for instance, relates to it in his works from 1948 on. In the third version of Hagar (1957), the artist adds the figure of the angel guarding the mother and the child. The subject is treated as an interplay of curvilinear forms, mingling mother and child in one continuous whole. For the artist, the sculpture symbolizes the prayer and hope for brotherhood between Jews (Isaac) and Arabs (Ishmael) in the recently established State of Israel.

A similar even-handed treatment which relates to both sides in the conflict is to be found in Jakob Steinhardt’s woodcuts from the 1950 and 1960s. He portrays Hagar carrying her weakened son Ishmael into the desert; raising her head, she opens her mouth to protest the wrong done to her child (Hagar, 1957). The bright background may imply that at this very moment the angel addresses her, giving her new hope.

Rebecca

With the help of Abraham’s servant Eliezer, Isaac meets Rebecca when he is forty years old. He takes her “into to his tent” and she becomes his wife (Gen. 24:10–26). After the birth of the twins Jacob and Esau, the family takes refuge in the land of Gerar ruled by King Abimelech, where Isaac passes his beautiful wife off as his sister. There Isaac receives the divine promise that his seed will propagate the race (Gen. 26:4–7). When Abimelech chances to see the couple making love, he forbids his people to touch Isaac or Rebecca, who are thereby protected and able to fulfill the Lord’s promise (Gen. 26: 8). Isaac and Rebecca are a seminal couple in God’s relation to humanity, whence the Christian theology holds them to be progenitors of Christ.

In the few illuminated Bibles of early Christianity the episode of the meeting between Eliezer and Rebecca is rendered as a pastoral genre scene, as exemplified in the Vienna Genesis (Constantinople, sixth century). The story is illustrated later in books and mosaics, usually in narrative cycles, where it follows the biblical text quite closely (Monreale Cathedral, c. 1175–1190).

The love-making of Isaac and Rebecca is particularly popular with Renaissance and Dutch art owing to the long tradition of biblical exegesis that sees in their relationship not only a licit liaison, but one inspired for the purpose of creating God’s Chosen People. This is exactly the moment Raphael (1483–1520) depicts in his Isaac Embraces Rebecca (Vatican Logge, 1516–1519). Portrayed as an amorous couple in sanctified, marital embrace, they are discovered by Abimelech. Rembrandt enlarges the biblical interpretation in his famous and enigmatic painting known as The Jewish Bride (1662–1666), now officially titled Isaac and Rebecca. The painting expresses the idea of love, based largely on the imagery of the Song of Songs, evoking the ideals of marriage, chastity and fecundity.

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780–1867), a great admirer of Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), copies the latter’s Eliezer and Rebecca (1648), which suggests the superlative beauty of Rebecca. In Ingres’s painting Rebecca (c. 1805) he reduces the large female group of Poussin to three, and suppresses the figure of Eliezer. Rebecca and her two female assistants are but one woman seen from different angles, echoing the classicist idea of female beauty.

While the cycle of Rebecca is rarely depicted in Jewish medieval art (Nuremberg The "guide" to the Passover seder containing the Biblical and Talmudic texts read at the seder, as well as its traditional regimen of ritual performances.Haggadah, 1470–1500), her theme is treated by several modern Jewish artists, for example by Chagall (Verve Bible, II, 1960), who depicts Rebecca and Isaac’s story as a family love story, only loosely connected to the biblical text. Whereas the text speaks of the servant Eliezer meeting Rebecca at the well, here it is Isaac who meets his future wife. The couple is also shown walking along, illustrating the verse “he took her into to his tent,” namely their becoming husband and wife; and Rebecca holding her child, a tender image of motherhood.

Rachel

The account of the meeting of Jacob and Rachel—Laban’s younger daughter and mother of Joseph and Benjamin—and the trials and tribulations Jacob endured in order to marry her, read like a love story (Gen. 27:46–28:5; 29:18; 31:14–21).

Jacob was seen in the patristic literature as a prefiguration of Christ and Rachel as the allegory of the Church and, by extension, of Mary. The marian parallels are exposed in the mosaic depicting her marriage to Jacob (S. Maria Maggiore, Rome, 432–440). Standing between Jacob and Rachel—clad like the Virgin Mary in a mosaic in the same church—Laban joins the young couple’s hands in the dextrarum junctio, symbol of the Christian marriage, conveying the idea of Christ espousing the Church.

In seventeenth-century Dutch art the episodes of Rachel often serve to depict a detailed and anectodal landscape, as for instance in Jan Steen’s painting Laban Seeks the Idols (1660–1671). Rachel, with Joseph in her lap, sits on the hidden teraphim of Laban. Her oriental sunshade and the camels “authenticize” the otherwise genre-looking scene.

Following the description of the two sisters in Dante’s Purgatorio, canto 27, where Leah and Rachel are the embodiment respectively of the active and contemplative life, Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) shows Leah on the right occupying herself with a spray of flowers and Rachel lost in thought (Dante’s Vision of Rachel and Leah, 1855).

Although Abel Pann painted the figure of Leah, it is Rachel to whose portrayal he repeatedly returned during his artistic career. In one of his works Rachel embodies a moving image of motherhood. Standing at the opening of her tent, she turns her face towards the radiant light outside, while embracing the small Joseph (Rachel, 1940s). After World War II, there appear mourning scenes featuring Rachel weeping for her children as well as scenes relating to the divine promise that her exiled children will return to their homeland (Jer. 31:14–16), as for example in Steinhardt’s woodcut Rachel (1953).

The Multifaceted Biblical Women

Eve is a recurrent subject throughout art history, while other female biblical figures appear intermittently; yet all images constantly fluctuate according to historical and social perceptions. Thus, Delilah, Potiphar’s wife and Judith are especially valued in Northern culture, where they serve to express the theme of woman’s domination and man’s subjugation through their charm and wily acts. Other figures such as Jael, Esther and Judith—known for their valiant deeds—become types in Christian reception and are therefore popular and admirable female models. The moralistic medieval visualization of Lot’s daughters, Bathsheba and Susanna, all implicated in sexual context, changes in Renaissance and Baroque art into a highly erotic image; featured as voluptuous, sensuous female nudes, they are intended to delight the gaze of the (mostly male) spectators. The conventionalized stereotypes of Sarah (Hagar), Rebecca and Rachel (Leah), valued in medieval thought thanks to their typological meaning, are frequently represented. In Netherlandish and German art, though retaining their Christian meaning, they also acquire a social connotation; they serve as paradigms of female virtues, incarnating chastity, obedience or marital fidelity. Jewish art prefers to turn both to heroic women who through their courageous deeds helped to triumph over Israel’s enemies (Jael, Judith, Esther), and worthy women (Miriam, Ruth). Lastly, Hagar and Rachel are undoubtedly the figures of choice of Israeli artists to convey their attitude towards the Jewish-Arab conflict.

Biblical Stories in Islamic Painting. Exhibition catalog. Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Dec. 1991–May 1992.

Bleyerveld, Yvonne. “Chaste, Obedient and Devout: Biblical Women as Patterns of Female Virtue in Netherlandish and German Graphic Art, c. 1500–1750,” Simiolus 28/4 (2000/2001): 219–236; Femmes de l’Ancien Testament.

Exhibit catalog. Musée National Message Biblique Marc Chagall, Nice, July 3–October 4, 1999.

Friedman, Mira. “The Metamorphoses of Judith.” Journal of Jewish Art, 12–13 (1986/87): 225–246.

Idem. Bilder zur Bible. Altes Testament, Bayreuth: 1985.

Garrard, Mary D. Artemisia Gentileschi. The Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art. Princeton, N.J.: 1989.

Hieatt, A. Kent. “Eve as Reason in a Tradition of Allegorical Interpretation of the Fall.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 38 (1975): 221–226.

Jacob and Israel. Homeland and Identity in the Work of Jakob Steinhardt. Exhibit catalog. The Open Museum, Tefen Industrial Park, January 1998.

Kahr, Madlyn Millner. “Delilah.” The Art Bulletin 54 (1972): 282–299.

Kunoth-Leifels, Elisabeth. Über die Darstellungen der “Bathseba im Bade.” Essen: 1962.

Kunz, Hannelore. “Materialen und Beobachtungen zur Darstellung der Lotgeschichte (Genesis 19:12–26) von den Anfängen bis gegen 1500.” Ph.D. diss., Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität zu München, 1981.

Lavin-Aronberg, Marylin and Irving Lavin. The Liturgy of Love: Images from the Song of Songs in the Art of Cimabue, Michelangelo, and Rembrandt. Lawrence, KS: 2001.

Mellinkoff, Ruth. “Sara and Hagar: Laughter and Tears.” in Illuminating the Book: Makers and Interpreters. Essays in Honour of Janet Backhouse, edited by Brown, Michelle and Scot McKendrick, 35–51. London: The British Library, 1998.

Meyer, Mati. “L’image de la femme biblique dans les manuscrits byzantins enluminés de la dynastie macédonienne (867–1056).” Ph.D. diss., Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2001.

Sed-Rajna, Gabrielle. The Hebraic Bible in Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts, Tel-Aviv: Steinmatzky, 1987.

Sölle, Dorothée. Great Women of the Bible in Art and Literature. English translation by Joe Kirchberger. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1994.

Unglaub, Jonathan. “Poussin’s Esther Before Ahasuerus: Beauty, Majesty, Bondage.” The Art Bulletin, 85/1 (2003): 114–36.

Veldman, Ilja M. “The Old Testament as a moral code: Old Testament stories as exempla of the Ten Commandments.” Simiolus 23/4 (1995): 215