Deborah Bertonoff

From her debut at age nine through her performances in her late seventies and teaching into her late eighties, Deborah Bertonoff made dance her life’s work. Bertonoff began studying at the elite Bolshoi School of Ballet in 1923. Her family moved to Israel in 1928 and together joined the Habimah Theater, becoming pioneers of Israeli dance. In 1926 Bertonoff began choreographing, incorporating Balinese, African, and modern dance with elements such as mime. Although she retired from the stage in 1970, she returned in 1985 with a new version of “Beggar’s Dance” and film roles such as 1992’s Amazing Grace. Along with her dancing and choreography, Bertonoff founded a dance studio in 1944, training children and professional dancers alike. She was honored with the 1991 Israel Prize.

Early Life and Family

Deborah Bin-Gorion (Bertonoff), a pioneer of Israeli dance and recipient of the 1991 Israel Prize, was born on March 12, 1915, in Tiflis (Tbilisi), Georgia in the former Soviet Union while her parents were on tour with a theater troupe.

Her father, Yehoshua Bertonoff (1879–1971), was among the foremost actors of the Habimah theater, which he joined in Moscow in 1922, and her mother Miriam (1891–1973) was also an actor. Deborah’s brother, Shlomo Bertonoff (1925–1977), was a radio announcer and taught in the Department of Theater Arts at Tel Aviv University. Her husband, Emanuel Bin-Gorion (1903–1986), was a writer and the son of Micha Josef Berdyczewski (Bin-Gorion), one of the giants of Hebrew literature. Her only son, Ido Bin-Gorion (1938–1972), was a man of many talents—translator, director, actor, poet and writer—who committed suicide at the age of thirty-five. In the mid-1960s the entire family moved into three apartments in a house in Holon. In the basement, Deborah set up a dance studio and Emanuel kept his father’s books and manuscripts.

Dance Studies

Deborah Bertonoff was raised in Moscow from 1922 to 1928. She began her dance studies in 1923 at the highly demanding Bolshoi School of Ballet, where she studied character dance and pantomime as well as ballet. In 1924, at the age of nine, she first appeared on stage with the Bolshoi Ballet, in which she was one of a group of children clustered under a canvas sheet representing the ocean. In the more than seventy years since then, she has been engaged in performing, teaching, and studying dance, in particular exploring various ethnic, liturgical, and folk dances.

In 1928 Bertonoff and her parents moved to Palestine and joined the Habimah theater company, which was then on an extended tour of the country. Here Deborah Bertonoff made her debut in the country in a solo performance entitled “The Little Dancer,” which was held in the loft of a barn that served as Kibbutz Deganiah’s “cultural center,” with the cows on the ground floor and culture and the arts on the floor above. At a party in honor of Habimah, she performed “The Beggars’ Dance” from The Dybbuk, directed by Yevgeni Vakhtangov, one of the dances still most closely identified with her. Hayyim Nahman Bialik, who was present, hugged and kissed her, congratulating her on her performance. When the troupe embarked on an American tour in 1929, her parents left Deborah in Berlin with a family friend, Fran Polotzky, who taught her German and Russian literature. During her years in Berlin (1929–1933), she studied modern dance with the master of dance Vera Skorone at the Truempi-Skorone school of dance. She also studied percussion with the composer Carl Orff (1895–1982) and Balinese dances from the Java Islands with Radn Maas Jodiane. To pay for her stay with Polotzky, Bertonoff performed in the homes of wealthy Berliners. Among these was Albert Einstein, who prophesied that she would be “the best pony in her stable.” From 1934 to 1939 Bertonoff studied in England at Dartington Hall, the dance school run by Kurt Jooss and Sigurd Leeder. It was Joos who introduced her to Dame Marie Rambert, who arranged for Bertonoff to perform before a group of artists and dance students. Through a member of the audience, she met Emanuel Bin-Gorion in October 1936. They married in May 1937 in the synagogue in Rehovot. Encouraged by Jooss, Bertonoff participated in the Paris International Dance Competition in 1936 while en route from London back to Palestine, appearing before a jury headed by dancer and choreographer Serge Lifar. An unknown dancer, she won first prize for her dances “Characters at a Wedding” and “The First Ball.”

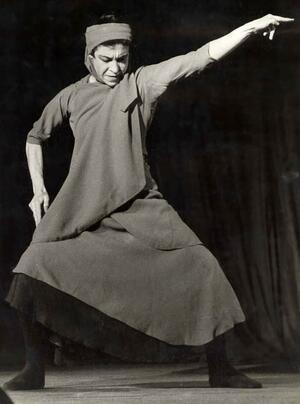

Performance Career

With the help of her father, Bertonoff created dances for her solo appearances. After “Wedding of the Youngest Daughter” (1926), she appeared in 1928 in “The Beggars’ Dance” from The Dybbuk and in 1930 in “Jephthah’s Daughter” (music by Nahum Nardi), “Abandoned Child” and “Characters at a Wedding.” In 1933 she performed her creations “Two Jews Talking” (music by Joel Angel) and “Maker of Magic.” “The First Ball” (music by Martin Penny) was created in 1935. The following year, she choreographed the dances “Shabbat” (music by Karel Salomon) and “Valley” and “The Mother” (music by Marc Lavry). “The Country Girl Comes to Town” (1938, music by Lavry) and the “Street of Sorrows” (1938) were followed by “The Teacher” and “The Pupil” in 1940. She also choreographed “The Woman Partisan,” “The Unknown Soldier” and “The Waiter” (Lavry) and “The Princess and the Pea” (music by Mozart) in 1943; “Exodus from Egypt” (music by Josef Tal) and “Yizkor” (music by Oedoen Partos) in 1946; “The Pioneer Woman” (Partos) in 1947; “Going Up to Jerusalem” (Tal) in 1952; and “Memories” (Tal) and “The Jester” (music by Hanan Winternitz) in 1957. In 1960 Bertonoff created dances based on Ghanaian-African motifs.

Bertonoff retired from the stage in 1970. In 1979 she created “Memories of a People” (Josef Tal) for the Batsheva Dance Company. In 1985, fifteen years after retiring, Bertonoff returned to the stage, appearing in a new version of “The Beggars’ Dance” at the Ninth Conference of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem and at the seventieth-anniversary celebrations of Habimah. In 1994, at the age of eighty, together with her longtime student, director Daniella Michaeli, she created “When the Lights Go Down” for the annual “Curtain Up” festival at the Suzanne Dellal Center for Dance and Theater in Tel Aviv; the piece was inspired by the works of Federico Fellini, in particular the sense of loneliness, sadness and pain that marks his oeuvre. The actor and dancer Ido Musseri also took part in the show.

Although “When the Lights Go Down” depicted an artist taking leave of the stage and passing the artistic baton to a younger man, Bertonoff took pains to emphasize that “this is not my farewell dance. Who can know when their time will come to step down? I try to listen to myself, do what I can, and work every day.” After returning to the stage, Bertonoff appeared in small roles in Gary Bilu’s production of The Effect of Gamma Rays on the Marigolds at the Beit Zvi Theater School (1991) and in Amos Gutman’s film Amazing Grace (1992).

In 1996 Bertonoff performed for the first time in a solo show that did not include any dance segments. She toured the country with the production, performing it over one hundred times over a period of three years. In 2000 she appeared in another Teatronetto production, Farewell to the Stage. A film about her, aired on television in summer 2003, showed the audience going up on stage, overcome with tears.

International Tours

For many years Bertonoff performed her solo shows overseas; her tours took her to Prague, Czechoslovakia, and the Baltic states in 1936; in 1948 to the United States, where she mounted a solo evening on Broadway; in 1960 to her first field trip to Ghana, Africa on a UNESCO scholarship, followed by a series of shows in Israel about the experience of dancing in Ghana. In 1962 Bertonoff represented Israel with a solo performance produced by her son Ido at the Théâtre de la Ville (formerly Théâtre des Nations) in Paris and at the International Mime Festival in Berlin. In 1966 she traveled to India, after which she toured Israel once more, performing, lecturing, and offering demonstrations of Indian dance, which developed into a “dance ethnography” of sorts. In 1979, Bertonoff toured dance schools in Los Angeles and New York.

Teaching Career

In 1933 Bertonoff taught modern dance for the first time at the conservatory established in Jerusalem by Emil Hauser and Thelma Yellin. Later, in 1944, she founded her own dance studio for children and professional dancers in Tel Aviv. In forty years of teaching, she developed a method that she terms “education through dance.” In instructing professional dancers, she placed an emphasis on “conscious action and maximum attention to the smallest details of performance, along with a sense of the firm connection between the music and the various dance techniques, since the interplay between the two art forms of dance and music is one of the key elements of dance.” A dance class given by Bertonoff would start with the basic elements—walking to the accompaniment of percussion instruments, which would evolve into running, skipping, and jumping. This was followed by improvisation exercises on such themes as “working in the fields,” “invention,” and the like. In every class, she aimed to surprise the children with some aspect of the music, tempo, or phrasing.

Bertonoff’s Artistry

All of Bertonoff’s appearances on the dance stage were solo performances. By her own definition (and as described by her husband Emanuel Bin-Gorion in Deborah’s book, Journey into the World of Dance), her works belong to a genre that is “a unique blending of stylized dance and ‘dumb show’”; and as defined by Deborah herself: “a shaping of characters who revealed their essence through a gesture, and dance, and through the fusion of seriousness into one unit; dances with national themes, based on anthropological and ethnographic elements; and a concentrated effort to fashion a style of movement that conforms to the theme.” At a later stage in her work, one can discern an attempt to break through to a form of dance that is abstract, stylized, conceptual.

Until the 1940s Bertonoff presented stories in which she traced emotional transformation through movement, placing her focus on identifying the motions associated with each character she portrayed (Eshel 1991, 23). From the mid-1940s on, she began the process of fashioning what she called “drama”—a work consisting of solo dances and passages of text read aloud whose subjects were largely biblical and/or nationalistic. Bertonoff argued that the women of the Bible, such as Jochebed, mother of Moses, and Deborah the Prophet, should not be treated as ordinary mother figures; it was necessary to find special ways of depicting them through movement. Hence she looked to ancient forms to find styles of movement appropriate to these biblical figures.

Writing in the daily newspaper Davar in 1952, the critic and author Yeshurun Keshet stated: “Her principal roles rest on a minimum of props. There is always an economy to her movements and a constant connection with the essence of the central motif; she succeeds in embodying a theme more through the intensity of movement than through the amount of variations and repetitions.” Earlier, in 1937, in Davar, a critic had written: “Deborah is the “mosaic” storyteller of dance. Everything she dances is reportage, a humorous story, sometimes a novella. There is a great astuteness to each of her dances, an abundance of humor, penetrating insight, passion, and movement. And mime above all.”

Later Life and Legacy

Early in 2002 Bertonoff fell and broke her thigh bone. After surgery and rehabilitation, she finally retired from performing, instead of writing her autobiography, Me-ahorei ha-kela’im shel ha-nefesh (Backstage of the Soul), which was published in 2005. “Few dancers are willing to take the risk of continual solo performances; fewer still are able to hold their audience’s attention for an hour,” wrote the art critic and poet Hezi Laskaly in a review dated November 17, 1989. “Deborah Bertonoff, who is nearing eighty, has done both—and this despite advancing age, the mortal enemy of dance.… Bertonoff belonged, from the outset to a generation that did not offer dazzling technique and therefore had little to lose with the passage of time. What she offered was expression, and that only improved with the years.”

Bertonoff belonged to the pioneers, to the early immigrants who brought with them a special combination of “intellect and naiveté,” in the words of Laskaly. To see her perform was “a visit, not to a moldy museum but, on the contrary, to a museum full of life that teaches us more than a little about ourselves.”

Of the tragedies in her life—the deaths of her only son in 1972 and of her husband in 1986—she stated: “I am a strong woman who gets back to work quickly. It’s not a strength—it’s a weakness. You cling with all your might to live, looking for a refuge” (Ma’ariv, November 3, 1989). When asked about post-modern dance, Bertonoff responded: “I don’t understand it very well. It’s all anarchistic. There’s no ‘how’ or ‘what.’ What are they trying to say? I’m not living in the past. All I’ve kept from the old days is my passion for the profession.”

Although Bertonoff symbolized modern dance, both European and Israeli, she had great respect for classical ballet. Following her appearance at the Karmi’el Dance Festival in 1991, a local reviewer wrote: “At the age of seventy-six, Deborah Bertonoff is being rediscovered—and what a discovery she is. Dancer, actress, scholar, writer, a pillar of hope and faith in a world that casts off and spruces up the same old suits. Unpretentious, diffident, and glorious, a ‘bride’ of the Israel Prize whose wedding it is our pleasure to dance at, or more precisely, an artist whose performance is an absolute joy and a learning experience …” (Hed ha-Kerayot, August 9, 1991).

In February 2005 the Holon theater held an evening in honor of Bertanoff’s ninetieth birthday.

Deborah Bertonoff was the personification of Jewish and Israeli life. For her, dance was a language; it was the “mirror of the soul.” In the words of the aging Russian ballerina in one of Bertonoff’s dances, who insisted on continuing to teach dance even at the age of 87: “Because dancing is giving, and you only take.” Bertonoff gave, and her public have all taken.

Deborah Bertonoff died on April 19, 2010.

Selected Works by Deborah Bertonoff

Dancing Toward Earth: A Journey through Ghana. Tel Aviv: 1964.

Dancing Toward the Horizon: A Journey through India. Tel Aviv: 1973.

Dance, Drums and Drama (Translated into English). Tel Aviv: 1975.

From Between the Curtains. 1971.

Dancing as the Spirit Moves You. 1981.

Journey into the World of Dance (which included her lectures at Haifa University between 1975 and 1977, on dance as an expression of the individual and the nation, and dance as an art form). Tel Aviv: 1982.

Dancing Toward Earth. Revised edition. Tel Aviv: 1985.

Backstage of the Soul. Tel Aviv: 2005.

Bertonoff also published several short works, among them “A Brief Look at Dance”; “A Time to Dance,” in memory of Valentina Arkhipova; “From Between the Curtains,” commemorating her brother Shlomo Bertonoff; and some two hundred “From Artist to Audience” columns in the Hebrew press, including Davar, Ha-Dor, Ha-Po’el ha-Za’ir, and Ma’ariv.

Eshel, Ruth. Dancing with the Dream: The Development of Artistic Dance in Israel: 1920–1964 (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: 1991, 23–24.

Interview with Emmanuel Bar-Kedma (Hebrew). Ma’ariv, November 3, 1989.