Bet Hillel and Bet Shammai

Bet Hillel and Bet Shammai are the two major schools of exposition of the Oral Law that existed from the first century BCE to the second century CE. Contrary to the common interpretations, Bet Shammai is more lenient than Bet Hillel in its rulings surrounding matrimonial law. Bet Shammai is trustful of a widowed woman’s testimony and argues for a coherent legal system that grants a widow financial resources regardless of the circumstances; Bet Hillel disagrees on both of these issues. Generally, Bet Hillel is more concerned with the familial complexity or unexpected events, and that less specific view leads to oppression of women’s autonomy in legal matters. Bet Hillel informed the creation of halakhah, and therefore has been unable to adapt to modern times.

The Disputes of Hillel and Shammai

Bet Hillel and Bet Shammai are the two major schools of exposition of Oral Law that existed from the first century BCE to the second century CE. Talmudic tradition lists over three hundred and fifty disputes or controversies between Bet Shammai and Bet Hillel, including more than sixty disputes that deal with issues of family law—that is, disputes in which women are incorporated into the The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhic discussion.

Traditionally, the sages have characterized the differences in rulings of the two schools as more restrictive on the one hand and more lenient on the other. Bet Shammai is generally more stringent or restrictive, while Bet Hillel is more lenient ((Aramaic) A work containing a collection of tanna'itic beraitot, organized into a series of tractates each of which parallels a tractate of the Mishnah.Tosefta Booth erected for residence during the holiday of Sukkot.Sukkah 2:3). Alternatively, Bet Shammai can be viewed as more intolerant, while Bet Hillel is more tolerant and takes into account people’s needs and sensitivities (BT Eruvin 13b).

Matrimonial Law

However, on two issues this characterization does not apply when it comes to matrimonial law. Firstly, matrimonial issues always involve two parties, the husband and wife, and therefore a stringent ruling for one is automatically a lenient ruling for the other. Moreover, it appears that in the majority of cases of disputes between the two schools on issues of matrimonial law, it is Bet Shammai that views women as autonomous individuals possessing equal personal status, while Bet Hillel disregards women’s personal status, thus seeming more restrictive to women.

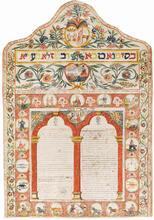

An example is the woman who arrives from a distant or isolated place and relates that her husband has died. She asks to be recognized as a widow and thus be eligible to receive her Marriage document (in Aramaic) dictating husband's personal and financial obligations to his wife.ketubbah. Bet Shammai accepts her request while Bet Hillel debates the issue, saying, “We have not heard [of accepting a woman’s word testifying to her husband’s death] except in the case of a woman who comes from the reaping [and says that her husband has died there], in the same region and as a specific incident that actually took place” (Codification of basic Jewish Oral Law; edited and arranged by R. Judah ha-Nasi c. 200 C.E.Mishnah Yevamot 15:2). In other words, Bet Hillel attempts to limit the instances, while Bet Shammai contends, “The sages always spoke in the present.”

Bet Shammai holds that the reaping is only a representative example of an isolated and far-off event and a woman’s testimony should be accepted in other cases of a similar nature. Thus, the woman’s lone testimony suffices to declare her a widow. In this case Bet Hillel retracts its opinion and agrees with Bet Shammai, thus accepting its social and practical logic. Thus, in this instance Bet Shammai is more attentive to the widow’s predicament, exhibiting—according to the modern legal understanding—greater sensitivity, while Bet Hillel initially adopts a more restrictive approach, distrusting the testimony of the woman concerned.

Bet Shammai here is also attentive to the legal status of women and demands a coherent legal system in which one ruling obligates the entire legal system, thus declaring her a widow and providing her with her financial resources. Bet Hillel, on the other hand, is more concerned with the possibility of familial complications and thus neglects formal and legal coherence. Finally, Bet Hillel changes its view and agrees to accept her testimony as regards her marital status and declare her a widow.

Modern Perspectives on Hillel and Shammai

Modern researchers argued for slightly different characteristics: Bet Hillel is more liberal (B. Z. Bacher, Tannaim, 15) and open to foreign influences such as Persia and Rome, while Bet Shammai rejects all foreign influences and focuses solely on Jewish tradition (Rosenthal). Alternatively, Bet Hillel takes into account public opinion and customs, while Bet Shammai is guided solely by stringent, formal The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah (Auerbach). Bet Shammai is more traditionalist, while Bet Hillel is innovative (Fish, Shapira, p. 469ff.). Unfortunately, all these categories are, in general, not relevant to disputes regarding women. Even more important is the fact that the researchers base their distinctions on disputes in the Statements that are not Scripturally dependent and that pertain to ethics, traditions and actions of the Rabbis; the non-legal (non-halakhic) material of the Talmud.aggdah and do not at all relate—either directly or tangentially—to the entire corpus of disputes in which women appear.

In contrast, Yisrael Ben Shalom’s study on Bet Shammai, which is based on excessive enthusiasm for its teachings, also touches on disputes that include women, claiming that it was Bet Shammai’s religious zeal that dictated their stance on women-related disputes. However, a close examination of Ben Shalom’s arguments reveals that his focus is on Bet Shammai itself and not on women. He thus defines Bet Shammai’s stance in different, even conflicting, ways: as judicial conservatism (Ben Shalom, Bet Shammai, 161), but also as social sensitivity, “so that the daughters of Israel shall not be abandoned” (ibid., 210ff.) and, in addition, as a strict and perhaps overly idealistic view of the institution of marriage (ibid., 212). Ben Shalom’s entire approach is characterized by inner contradictions as well as lack of feminist critique. Focus on Bet Shammai takes precedence over interest in women’s legal and social standing.

The disputes of Bet Hillel and Bet Shammai have been discussed from a feminist perspective in the works of Judith Romney Wegner and Judith Hauptman [link to new entry on Judith Hauptman]. Both of them take a mostly legalistic approach to the disputes, analyzing them for their legal effect on women rather than the social or philosophical nature of rabbinic law. Tal Ilan argues in her book Integrating Women into Second Temple History that women, particularly aristocratic women, were attracted to the Pharisaic movement in the Second Temple era and especially to Bet Shammai.

Judith Romney Wegner poses a number of questions that have their source in feminist criticism, the most important of which is expressed in the very title of her book: Chattel or Person? However, her approach is mainly legalistic and although she refers to Mishnaic or Lit. (from Aramaic teni) "to hand down orally," "study," "teach." A scholar quoted in the Mishnah or of the Mishnaic era, i.e., during the first two centuries of the Common Era. In the chain of tradition, they were followed by the amora'im.Tannaitic law she does not deal at all with issues of social or philosophical analysis of rabbinic law. Regrettably, she deals neither with the distinction between Bet Hillel and Bet Shammai nor with their influence and significance in shaping tannaitic halakhah. While women are at center stage in her work, Bet Hillel and Bet Shammai are relegated to the margins of feminist research and remain there to this very day.

Women’s Legal Rights

One can argue that from a philosophical point of view Bet Shammai is almost theocentric: God is at the very center of its religious and halakhic reasoning, while in Bet Hillel’s religious reasoning the religious person who aspires to carry out God’s will is central. The disputes on women-related issues can then be added to those which are explicable by this difference between the two schools. The above hypothesis may serve to explain Bet Hillel’s severity in some cases, as well as its greater leniency in others, as against Bet Shammai’s more formal and respectful stance, which seems more sympathetic to women’s autonomy. One outstanding example is that cited at the beginning of this article: Bet Shammai’s acceptance of the testimony of the woman whose husband died in a distant land. Bet Shammai reached the conclusion that “she may marry and also claim her ketubbah” (Mishnah Yevamot 15:3). Since her testimony is admissible, she is free to start a new life and also entitled to the economic protection that the marriage contract bestows on a widow.

But Bet Hillel declares, “She may marry, but not claim her marriage contract.” According to Bet Hillel, she is released according to the laws of matrimony but not as far as monetary laws are concerned since these may be judged only in a Lit. "house of judgement." Jewish court of lawBet Din with two witnesses. In other words, since her release was not carried out in an orderly legal framework, she is not entitled to receive her marriage contract. So, while Bet Shammai draws the full legal conclusion and frees the woman from all dependencies, Bet Hillel separates the financial contract from the discussion of her personal matrimonial status. Bet Shammai grants the woman organized legal status, while Bet Hillel weaves the social system into the discussion. Payment of the ketubbah remains a kind of bargaining chip in verifying the credibility of the woman’s testimony. But this “social sensitivity” leaves the widow without economic support. Thus, from the point of view of women, the social consciousness of the liberal Bet Hillel school becomes their nemesis, while the formalism of Bet Shammai grants women autonomy and personal status.

This distinction holds good in another important controversy, regarding the relationship between two women married to one and the same man, who died childless (zarat ervah—a co-wife of a prohibited relation; e.g., if one widow is the daughter of the deceased’s brother). “Bet Shammai permits the non-related widow to marry the brother, and Bet Hillel forbids her” (Mishnah Yevamot 1:4). According to Bet Shammai, from a legal point of view there is no point in linking the fate of the two widows together. The widow who is the daughter of the deceased’s brother cannot enter into a Marriage between a widow whose husband died childless (the yevamah) and the brother of the deceased (the yavam or levir).levirate marriage because it is a prohibited marriage, while the other widow is an autonomous person unto herself and can marry the brother of the deceased. Bet Hillel holds the opposite opinion: the two women are not autonomous; their status is conditional on their being the ex-wives of the same deceased and their destinies continue to be interconnected. We can assume that Bet Hillel was afraid of the confusion that might ensue in the family if one of the widows was allowed to marry but not the other, and thus preferred to take into account the real-life family situation rather than the legal one.

It is precisely this social sensitivity that explains the salient differences between the two schools regarding the laws of a daughter’s refusal (me’un ha-bat); that is, the right of a minor girl whose father has died to object to a marriage arranged for her by her mother or brothers and where a bet din annuls her marriage (Mishnah Yevamot 13:2). The “daughter’s refusal” is an innovation crafted by the sages and both Bet Hillel and Bet Shammai accepted it as part of the halakhah, yet there are many disputes between the two schools regarding various details. Bet Shammai attempted to anchor the right of refusal within the legal system, while Bet Hillel anchored it in the social system.

Thus, Bet Shammai maintains that the refusal must be performed before the bet din, while Bet Hillel maintains that the refusal may or may not be performed before the bet din (Mishnah Yevamot 13:1). The Talmudic discussion elaborates in the spirit of Bet Hillel: “Rabbi Hanina said: There was the story of a little girl who went to buy flax from the flax seller. They said to her: ‘How is your fiancé?’ She answered, ‘Let his own mother go marry him.’ The incident was brought before the sages and they said: ‘There is no greater evidence of refusal than that. We learned in the name of Rabbi Yodah: Even if she had entered a store only to get something from the shopkeeper and said, “I can’t stand so-and-so as my husband,” there is no greater refusal than this’” (JT Yevamot 13:1, 13c).

An even more extreme case is “The daughter-in-law of Rav Yishmael expressed her refusal, and her son was on her shoulder” (JT Yevamot 13:1, 13c). Despite the fact that she had a baby, irrefutable proof that she was actually married, as a minor whose father had died, she had the right of refusal and her marriage was declared to be annulled. She is not a divorcée but a “refuser.”

Halakhic Ramifications

The philosophical-halakhic positions of the two schools also determine their halakhic stance on everything related to women’s issues. The conservative religious-legal viewpoint grants women a more egalitarian social position, while precisely Bet Hillel’s sensitivity to familial complexity and the vicissitudes of life turned women into those who pay the personal price for the sake of family and society. Thus Bet Hillel, with its more broad-minded and lenient bent, paradoxically turns out to be antithetical to basic feminist concepts of equality and personal autonomy.

Moreover, since halakhah is determined according to Bet Hillel, it has lost the ability to undergo adaptation in light of modern influences and structural changes in family and society. Laws of matrimony and personal status have been determined in accordance with societal and familial frameworks of the early centuries of the Common Era, when Bet Hillel still functioned within a living social framework. But halakhah was determined for all future generations as well. Thus, today’s laws of matrimony and the personal status of women still reflect Bet Hillel’s ancient stance, but their essence has been totally transformed. Today they are no longer part and parcel of contemporary societal sensitivity, but rather an expression of lack of sensitivity, both legal and social.

Behar, Benyamin Ze’ev. The Aggadot of the Tannaim (Hebrew). Jaffa: 1920–1923.

Ben Shalom, Yisrael. Bet Shammai and the Struggle of the Zealots against Rome (Hebrew). Jerusalem: University of Ben Gurion, 1994.

Frankel, Zekharyah. Methods of the Mishnah, the Tosefta, Mekhilta and Sifri (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: Sinai, 1959, 48–49.

Rosenthal, Eliezer Shimshon. “Halakhic Tradition and Innovations in the Mishnah of the Sages” (Hebrew). Tarbiz 63 (1994): 321–338.

Schwarz, Adolf. Die Erleichterungen der Schammaiten und die Erschwerungen der Hilleliten. Wien: Israelitisch-Theologische Lehranstalt, 1893.

Shapira, Hayyim and Menahem Fisch. “The Polemics of the Schools: The Meta-Halakhic Disputations between the Schools of Shammai and the Schools of Hillel” (Hebrew). Iyyunei Mishpat 22/2 (1999): 461–497.

Sonne, I. “The Schools of Shammai and Hillel from Within.” In Essays in Greco-Roman and Related Talmudic Literature, edited by H. Fischel, 94–110. New York: Ktav Publishing House, 1977.

Urbach, Ephraim E., The Sages: Their Concepts and Beliefs. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1979.

Wegner, Judith Romney. Chattel or Person: The Status of Women in the Mishnah. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Zevin, Solomon Joseph. “The Systems of Bet Shammai and Bet Hillel.” In Le-Or ha-Halakhah (Hebrew). Jerusalem: Mosad HaRav Kook, 2004, 394–402.