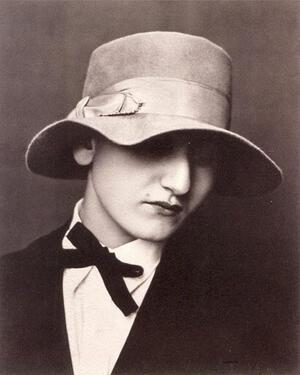

Anita Brenner

Anita Brenner, an anthropologist, journalist, and art historian, was born in Aguascalientes, Mexico, to Jewish immigrants from Latvia. Her family fled Mexico for Texas when she was elevent years old; the internal tension she experienced as a Jewish Mexican girl across the border led her to take a train from her home in San Antonio to Mexico City at the age of eighteen, where she formed part of the Mexican Renaissance cultural scene. Brenner’s complex relationship to her Jewishness provided her with insight into Mexican identity. She wrote her observations of the emerging Jewish community in Mexico and sent them to Jewish journals in the United States as she transformed herself into an expert and insider on the Mexican Jewish community.

In 1925, just over one year after she had returned to Mexico, anthropologist Anita Brenner wrote: “After all, I am glad I am a Jewess. And I do not say this with the defensive aggressiveness that the phrase ‘and proud of it’ usually carries. Devils, rebels or angels, poets or peddlers, princes or pawnbrokers, we really are not so bad, after all. At least we are interesting” (“A Jewish Girl of Mexico,” Brenner, 1925).

Early Life and Family

Anita Brenner’s father and mother, Isidore and Paula, were both natives of Goldingen, a small town near Riga, Latvia, but they met in a boarding house in Chicago, where they had both arrived in the 1880s. Paula worked in a sweatshop, while Isidore had recently arrived in the city after spending time in Iowa and then El Paso, Texas (Miller 162). After a week’s courtship, the couple married, and Isidore began planning to return to El Paso, where the newlyweds lived for a year before settling in Mexico (Mart 194). They then traveled to Aguascalientes, Mexico, where Mexican President Porfirio Diaz promoted foreign investment and converted the town into the headquarters of United States companies like the Smelting and Refining Company, owned by the Guggenheim brothers (Grabinsky 1). Isidore hoped to prosper in the cosmopolitan town, booming with foreign capital.

Registered as Hana Brenner on her birth certificate, Anita Brenner was born on her family’s ranch on August 13, 1905. Her parents worked at the Baños de aguas termales de Ojocaliente, a spa known for its hot springs, Isidore as a waiter at the spa and Paula as a cook. Eventually, Don Isidoro, as he was known in Aguascalientes, became manager of the spa, and Paula raised their five children. Brenner and her four siblings, Dorothy, Henry, Milton, and Leah, attended school at Colegio Morelos, the first Protestant missionary institute in Aguascalientes. Classes were taught in English to children of foreigners enrolled there (Glusker 21).

Like most Jews who immigrated to Mexico in the late nineteenth century, the Brenner family was not part of a formal Jewish community. They remained isolated and silent about their religion. As a young girl, Brenner was introduced to Judas, a children’s toy. The Jew, to her early understanding, was an evil spirit and Easter firecracker. Serapia, her Catholic nanny in Aguascalientes, described a Jew to her as a devil with horns and a tail. When Brenner was excused from religion class at Colegio Morelos, she realized she was different from the other children (Glusker 27).

When revolutionaries arrived in Aguascalientes, the Brenner family was forced to leave on three occasions: 1912, 1914, and 1916. In 1916, when Brenner was eleven years old, the family fled Mexico to San Antonio, Texas, where Brenner lived until she returned to Mexico in 1923 at the age of eighteen. In Texas, she repeatedly faced anti-Semitism and developed a deep resentment about her Jewish background. Brenner graduated from Main Avenue High School in San Antonio. Because of her limited access to her Jewish background and the challenge of balancing multiple identities, she continued to feel like a social outcast, rejected by her Jewish peers.

Brenner studied for one semester at Our Lady of the Lake College, where the Catholic atmosphere prompted her preliminary search for her own spiritual identity through Jewish literature and mysticism (Mart 194). She then transferred to the University of Texas for two semesters, where she encountered a lack of inclusion and anti-Semitism because of her Mexican and Jewish identities. She was moved from one rooming house to another when her landlord discovered her Jewish background (Glusker 30).

Tired of being treated as an outsider, in 1923 Brenner insisted on returning to Mexico. Isidore consulted with Rabbi Ephraim Frish of San Antonio’s Temple Beth El, who assured him that his daughter would be safe there. A letter from Frish introduced Brenner to Rabbi J.L. Weinberger, head of the Mexican B’nai B’rith, who confirmed he would meet her upon arrival. That September, Brenner traveled to Mexico City by train, intending to study and work there.

Transnational Cultural Interpreter

Anita Brenner’s status as a transnational Jewish woman allowed her to enter distinct and often contradicting social circles. The increase in Jewish migration to Mexico coincided with political and cultural upheaval in the country, and Brenner thrived among avant-garde artists and politically active intellectuals who defined the era. She helped coin the term “Mexican renaissance” in 1925, about the ongoing artistic revolutionary process of the time, which she preferred to spell Mexican Renascence “in the sense of constant rebirth” (Glusker 89).

Brenner became immersed in Mexico City’s post-revolutionary cultural scene, a period marked by artists who returned from post-war Europe to Mexico. These artists participated with passion in the rebuilding of Mexico through their artistic expressions, such as painting public murals. They established a visual interpretation of Mexican history and culture that became emblematic of the new revolutionary social order. Mexican muralists placed a romanticized indigenous past alongside utopian visions of an industrialized mestizo future on the walls of public buildings. In this context, Brenner went from a problematic relationship with her Jewish identity to a rediscovery and embrace of her roots. Her published and unpublished manuscripts, diaries, and newspaper articles demonstrate her commitment to defending and interpreting the Jewish immigrant experience in Mexico City and the community the immigrants formed there.

Development of a Transnational Mexican Jewish Identity

Through her connection to Weinberger, who was married to Frances Toor, a Jewish American author, publisher, and anthropologist, Brenner joined Mexico City’s world of writers, artists, and intellectuals. Though Toor and Brenner would later become rivals (Brenner listed Toor’s name under the category “enemies” in her diary), Toor was the first to introduce her to other foreigners and intellectuals in the city, such as journalist Carleton Beals and muralist Diego Rivera (Lopez 108). Toor and Weinberger lived in an apartment that overlooked a shared courtyard, with neighbors such as Beals and Ella Wolfe, who became Brenner’s mentors and friends (Glusker 33). Toor took Brenner to the Young Men’s Hebrew Association for tea and dancing.

Brenner collaborated on projects with Jean Charlot, an avant-garde French painter of Mexican heritage who arrived in Mexico in the 1920s. Manuel Gamio, a Mexican anthropologist influenced by Franz Boas, taught Brenner at la Escuela de Altos Estudios, part of the National University (today known as the School of Philosophy and Letters). At the same time, she served as his translator and editor.

Most scholars have only noted Brenner’s Jewish identity in passing, but Rick Lopez emphasizes “her complex relationship to her Jewish heritage that attuned her to Mexico’s denigrated indigenous traditions” (124). As he argues, Brenner’s role as both an outsider and an insider fueled her promotion of indigenous culture as the foundation for Mexico’s post-revolutionary identity vis-à-vis her search for a Mexican Jewish identity. Brenner intended to research and identify a historical Jewish presence in Mexico in support of her claim of Mexico as an appropriate place for Jews to settle. In October 1924, she was hired as a Mexico correspondent for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. That same year, she traveled to Guadalajara, Guanajuato, and Veracruz for research and social purposes, expanding her networks beyond the capital. In cafés and parties with artists such as Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, and José Clemente Orozco, she established herself as a journalist, anthropologist, and cultural promoter. According to Lopez, “Brenner was thrilled when her bohemian friends took an interest in her Jewish heritage. Embarrassed by her inability to answer their questions about Judaism, she set out to learn more about her religion and history, study Hebrew, and consider what it meant to her, personally, to be a Jew” (125). Thus Brenner, as a secular Jew, found comfort in the bohemian circles of which she was a part, where her otherness was embraced and considered exotic and where she could explore what it meant to be both Mexican and Jewish. Her hybrid identity allowed her to interact across national boundaries and play an essential role as a cultural diplomat.

As Brenner embarked on her journey of acceptance of her Jewish identity, she explored the identity of Jews in Mexico and defended their right to reside there. As a self-taught journalist writing during the period of Mexico’s post-revolutionary identity formation, her work reflects the perplexity of her time as she fluctuated between embracing Mexico as a place for Jews and revealing the realities of anti-Semitism and ignorance. Brenner’s multiple identities (Jewish, New Yorker, Texan, Latvian, and Mexican) allowed her to interact, understand, and connect otherwise separate cultural, linguistic, and political circles. Through her work with immigrants at the international Jewish service organization B’nai B’rith, publications for Jewish journals, and interactions with Jewish intellectuals in Mexico, she gained self-confidence. She affirmed herself as both Mexican and Jewish. In Mexico, surrounded by artists and intellectuals, she embraced her Jewishness as exotic and romantic. As she took on national, cultural, and artistic projects within and beyond Mexico City (including cultural journalism, bilingual publications, and research projects dedicated to Mexico and its indigenous populations) and explored Mexicanidad, she developed a more complex understanding of Jewishness in Mexico.

Commitment to Mexican Art

In addition to exploring her own Jewish identity and the Jewish community in Mexico, Brenner undertook a lifelong commitment to Mexican art. She admired Gamio, the father of Mexican anthropology, who investigated cultural survival under colonial rule. The phrase he coined to describe this phenomenon, “Idols Behind Altars,” became the title of Brenner’s book (Azuela 157).

Prior to enrolling in the Department of Anthropology at Columbia University in September 1927, Brenner worked as a research assistant on Ernest Gruening’s book, Mexico and Its Heritage (Gruening, 1928). Gruening, was a liberal United States journalist, editor of The Nation, and future governor of Alaska, and Benner introduced him to Mexico’s intellectual circles. Brenner traveled to New York with the National University’s Catalogue of Mexican Decorative Arts and her manuscript about art, entitled “Mexican Renascence” (Azuela 156). She combined both manuscripts into one volume entitled Idols Behind Altars, published in English in 1929. Writing for foreign readers, Brenner presented Mexico’s customs, traditions, peoples, and politics through a multidisciplinary approach. She included drawings and sculptures by modern Mexican artists and the equivalent resurgence of authentic Mexican art during this period. Although Idols Behind Altars includes no direct references to Judaism, “Brenner’s interest in Mexican art represented a version of her explorations of Jewish identity or even the search for her place in Mexican society as Jew…[H]er negotiation of multiple identities was not a simple-minded endeavor, nor can it be traced to any literal manifestation in the art she promoted” (Indych,151). Franz Boas encouraged her to pursue an advanced degree. Despite never earning a bachelor or master’s degree, Brenner completed her doctoral degree in Anthropology at Columbia in 1930. She won a Guggenheim fellowship and returned to Mexico in 1930, eager to explore Mexico with the grant funds. The same year, she was placed on the Jewish Honor Roll in the New York Times, along with Waldo Frank, Walter Lippmann, and Ludwig Lewisohn (Glusker 17).

As a promoter and influencer of Mexican culture abroad, in the mid-1950s, Brenner created Mexico This Month, a monthly magazine published from 1955 to 1972. The magazine included poetry, archaeology, and decorative arts. It also had a calendar of fiestas, where to go, places to visit, sports, theater, music, food, customs and traditions, advertising, and an art feature about an artist or a theme (Ugalde Gomez 146).

Marriage and Children

On June 18, 1930, Brenner married David Glusker, a Jewish American World War II veteran and medical student, in New York. With him, she explored the southern state of Guerrero. They had two children, a daughter, Dr. Susannah Joel Glusker (1939-2013), who taught at the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City, and a son, Dr. Peter Glusker (1936–2020), a physician who had a medical practice in Fort Bragg, California. Brenner and Glusker separated in 1951, ten years before Glusker’s death from cancer in 1961.

Legacy

Although Brenner’s life and work have remained in the margins until recently, she serves as an exceptional embodiment of the very nature of interdisciplinary studies and the importance of preserving and discovering overlooked and understudied archival material. After Brenner’s death, her daughter released a posthumous volume Avant-Garde Art & Artists in Mexico: Anita Brenner's Journals of the Roaring Twenties, prepared using Brenner’s diaries and notes from 1925 until her marriage in 1930 as well as photographs from Brenner's files. The Skirball Cultural Center exhibition titled “Another Promised Land: Anita Brenner’s Mexico” explored Brenner’s vision through works of art and archival documents. The exhibition was followed by a catalog with six essays offering an interdisciplinary approach to Brenner’s work. Before the Skirball exhibition, only one other exhibition had focused on Brenner; it was presented by the Museo Mural Diego Rivera in Mexico City in 2005 and titled Los ídolos, los altares y el arte en México. The exhibition displayed Brenner’s art collection to reflect her contributions to Mexican cultural history and is documented in the volume Anita Brenner: Visión de una época (2006).

When the Mexican government offered Brenner the Aztec Eagle Medal, the highest official honor available to a foreigner, she rejected the award. She did not consider herself a foreigner to Mexico (Lopez 114). On December 1, 1974, at the age of 69, Anita Brenner died in Ojuelos de Jalisco, 83 kilometers east of Aguascalientes, in an automobile accident. The pioneering efforts by Brenner to transform and stretch the borders of mexicanidad and Mexican Jewish identity may be used as an example for marginalized communities today, in both the United States and Mexico, and as a historical-cultural bridge between the two countries.

Selected Works by Anita Brenner

Idols behind Altars. New York: Payson & Clark, 1929.

“Assimilation in Mexico.” Jewish Morning Journal, December 1925.

“Judas and Kapores. A Story of Jews and Illiterates in Mexico Told by a Mexican Girl.”Jewish Morning Journal, August 16, 1925.

“Jewish Brides to Mexico: Mexican Jew Still Imports His Bride.” Special for International Jewish Press Bureau, 1924.

"Jews of Mexico Import Brides," special for The Jewish Woman, December 26, 1924.

“A Jewish Girl of Mexico.” Jewish Daily Forward, May 1925.

“The Jew in Mexico.” The Nation, August 27, 1924.

The Carvajal Story, typescript of an unpublished book, Anita Brenner Archives, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, the University of Texas at Austin.

The Jew in Mexico: Another Promised Land, typescript of an unpublished book, Anita Brenner Archives, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.

Anita Brenner Archives, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.

“Coolidge Proclaims Immigrants Quotas,” The New York Times, New York, July 1, 1924.

Cimet, Adina. Ashkenazi Jews in Mexico: Ideologies in the Structuring of a Community. Albany, NY: State U of New York, 1997.

Glusker, Susannah. Anita Brenner: A Mind of Her Own. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1998.

Grabinsky, Alan. “The Revolutionary Jewish-American Woman Who Exposed Rivera, Kahlo, and Siqueiros to the World.” Remezcla, August 1, 2017.

Lopez, Rick. “Anita Brenner, Jewish Roots, and the Transnational Creation of a National Identity.” In Creating an Archetype: The Influence of the Mexican Revolution in the United States (Washington DC: Smithsonian, 2013).

Lopez, Rick. Crafting Mexico: Intellectuals, Artisans, and the State after the Revolution. Duke University Press, 2010.

Roger Daniels, “Immigration Law,” The Oxford Companion to United States History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Ugalde, Nadia, et al. Anita Brenner: Visión De Una Época. Editorial RM, 2007.

Yolanda Padilla Rangel, México y la Revolución mexicana bajo la mirada de Anita Brenner. Instituto Cultural de Aguascalientes: Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes.