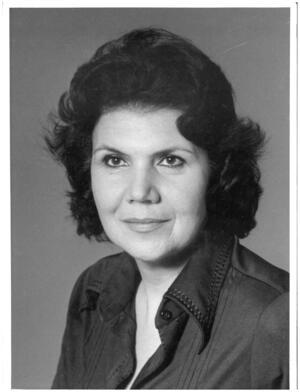

Selma Browde

Selma Browde was a medical doctor and activist whose passionate work and advocacy on behalf of disadvantaged communities in South Africa spanned more than half a century. Born in Cape Town to a middle-class Jewish family with roots in Lithuania and Ukraine, Browde studied medicine in Cape Town and Johannesburg, specializing in Radiation Oncology, and later became Head of the Department of Radiation Oncology at the Johannesburg General Hospital. As a cancer therapist and researcher; as a progressive politician in City and Provincial governments; as an activist tackling lack of services, evictions, and hunger under Apartheid; and, after retiring from her Academic post, as a Palliative Medicine pioneer, Browde’s life and work was of consistent benefit to others, especially those on the economic margins.

Selma Browde was a medical doctor and activist whose passionate work and advocacy on behalf of disadvantaged communities in South Africa spanned more than half a century.

Early Life and Schooling

Browde was born on July 21, 1926, in Cape Town, South Africa, to a middle-class Jewish family with roots in Odessa (Ukraine) and Lithuania. When she was four years old, her parents, Adolf and Frieda Meyer, took her and her younger brother, John, to Edinburgh, Scotland, where her father studied medicine.

After four years in Scotland, the family returned to South Africa and Adolf Meyer set up a general practice in Maitland, a suburb of Cape Town. The first school Selma attended in South Africa was The Holy Cross Convent. It was not common for Jewish girls to go to convents, but it was not unheard of either, if those girls lived, as the Browdes did, with no other schools within walking distance.

During that year (1935), a private Hebrew tutor, hired by Browde’s parents, came to the house to teach her the rudiments of the language. This arrangement lasted only six months. Towards the end of 1935, after nine months at Holy Cross, Browde transferred to boarding school at Good Hope Seminary in Gardens, where she completed her primary schooling.

In 1940, she moved to Rustenburg Girls High School in the suburb of Rondebosch, where she matriculated in 1943. The following year, Browde began her medical studies at the University of Cape Town.

Marriage and Early Employment

In December 1947, at the end of her fourth year of medical studies, Selma married Jules Browde, a World War II veteran seven years her senior who was then completing his war-interrupted law degree at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits).

Jules lived in Johannesburg and Selma planned to transfer to Wits Medical School, such transfers being common at the time in the later years of study. She was refused admission, apparently because the medical school was overfull owing to an influx of returning soldiers. Since Jules would begin working as an advocate at the Johannesburg Bar the following year, she had little choice but to give up her medical studies.

Browde spent the next eight years working in various jobs to supplement the family income while Jules built up his practice as an advocate. She worked in the Medical Institute doing manual blood counts, as a lampshade painter in a factory, as a florist, and selling advertising space, among other jobs. During this period, she gave birth to two sons, Ian and Alan.

In 1956, Browde reapplied to Wits Medical School and was accepted into third year.

Medicine 1959-1972

Browde qualified as a doctor in 1959. After her internship in 1960 (during which year she gave birth to her third son, Paul), the Radiation Oncology Department at the Johannesburg General Academic Hospital offered her the position of senior houseman in their ward for patients of color in the so-called Non-European Hospital, opposite the Johannesburg General Hospital – the only department that would allow her to work part-time. (“Houseman” in South Africa refers to a newly qualified doctor working in a government hospital; the first year after qualifying one is a "junior" houseman, and a "senior" houseman the two years following that.)

In 1964, Browde began working as a registrar in the Radiation Oncology Department at the Johannesburg General Hospital to study for the specialist degree in Radiation Oncology. She received her specialist degree in 1967 and was then appointed as a senior consultant and student lecturer in that department. In the early 1980s she was appointed Professor and Head of Department.

Politics 1972-1978

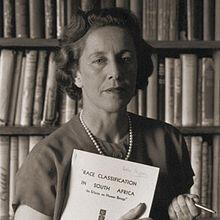

In 1972, at the urging of Progressive Party MP Helen Suzman, Browde stood for election to the Johannesburg City Council on a Progressive Party (PP) platform. She did so despite not being a member of that party. Browde had been a member of the Liberal Party, which disbanded in 1968 after the apartheid government passed legislation forbidding mixed-race membership of political parties.

Both the Progressive and Liberal parties had had some members of color. The smaller Liberal party decided to disband rather than be all white, whereas the PP chose to continue as an all-white party, believing that some opposition to apartheid was needed in parliament. The PP was considered the left wing of the all-white parliament. (For 13 years Helen Suzman was the lone Progressive Party MP.)

Unlike many white members of the disbanded Liberal Party, Browde had not joined the PP because she did not agree with their policy of “qualified franchise,” which favored limits on the franchise, but based on property ownership and other qualifications rather than on race. Browde believed in universal franchise. She stood for election to the City Council on a PP ticket only because of her personal admiration for Suzman, who had asked her to stand, and because she was convinced that as a non-member she stood no chance of winning.

To Browde’s surprise, of fourteen PP candidates on the roll, she was the only one to win election to the City Council.

The council at that time was dominated by the center-right United Party and the ruling, right-wing Nationalist Party, both of which were committed to protecting and promoting white interests only. Browde thus became the unofficial representative of many of the voteless African, Indian, and Coloured communities forced to live in separate “townships” around Johannesburg.

Browde retained her post in the Radiation Oncology department and pursued her council work from a home office, to which as many as 20 people from various “townships” came daily seeking help or advice. If she was at work when they arrived, her secretary would assist them.

While on the United Party-controlled City Council, Browde proposed motions on a range of issues, mostly concerning the townships, which were otherwise largely ignored by the council because township residents were voteless. While some failed, a few important ones succeeded, including in Soweto, the country’s largest township. In 1972/73, for example, Browde won a major fight for high-mast lighting to be installed over the whole of Soweto. In 1973/74 she initiated a process that led to the comprehensive electrification of the township by a private company.

In 1974, Browde was elected to the Transvaal Provincial Council. She had to resign her post in the Radiation Oncology department because the Johannesburg General Hospital was a Provincial Hospital and remaining would have led to a conflict of interests, although she did continue lecturing medical students. Browde was one of only two progressives on the Provincial Council, and she used her seat to push various progressive agendas, especially in healthcare.

Browde also pursued her activism beyond the confines of the city and provincial councils. Among many other initiatives, she founded the Soweto Basketball Association (1974) with Soweto resident Dan Teketle, to harness the energies of unemployed youth; she joined human rights lawyer Shun Chetty to start Action to Stop Removals (ActStop) in 1976, to fight forced removals conducted under the Group Areas Act; and, with Dr. Nthatho Motlana, she started the Hunger Concern Programme. In 1979, at her request, John Reese of the Institute of Race Relations took over this program and together they renamed it “Operation Hunger.”

End of Politics and Return to Medicine

In 1978, Browde resigned her position on the Provincial Council after her inquiries into corruption allegations were repeatedly obstructed. She returned to her post in the Radiation Oncology department.

In 1982, four years after her return—during which time she conducted a successful research project using lumpectomy instead of mastectomy in selected cases of early-detected breast cancer—Browde became Head of the Department of Radiation Oncology. Shortly afterwards she was formally appointed Professor, a position she held for four years. Browde retired from her post for health reasons in 1986.

After Retirement: 1986–2023

After her retirement, Browde became involved in Palliative Medicine, which includes pain management. Her advocacy resulted in the formation of a committee to formulate a Palliative Medicine policy within the Gauteng Health Department, although she remained frustrated by the lack of active implementation after the committee gave its report.

In 1998 she founded the Palliative Medicine Institute (PMI), with premises at Baragwanath Hospital’s nurses’ training facility. The PMI expanded the World Health Organisation’s definition of Palliative Care to include the relief of suffering (physical, emotional, and psycho-social) of all patients at all stages of any illness or condition, not just for seriously ill or terminal patients. The institute also promoted the need for all doctors and nurses to receive a basic training in palliative care.

Browde’s work also focused increasingly on the epidemics of HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis (TB) in South Africa. In 2000 she founded the NGO Parents for Aids Action, to impact both of these epidemics, starting in Alexandra Township, mainly to educate people about HIV/AIDS and so to break the stigma that was (and still is, to some extent) attached to the virus. Realizing that one cannot teach people about HIV and TB separately, she changed the name of the organization to Community Action in 2002 and developed the Community Action Street-based Primary Health Model to teach healthy living, and how to prevent the spread of these epidemics, to residents in their own homes.

In 2001 Browde founded the CMJ Academic Hospital Palliative Care Team after the then-Head of Medicine at the Charlotte Maxeke Johanneburg Academic Hospital requested that she address the suffering he was witnessing in the hospital.

In 2002 Browde completed development of Community Action’s Street-based Primary Health Model and piloted it in 3000 households in Alexandra and Soweto. In 2007/8, the pilot was evaluated by a private international monitor funded by Atlantic Philanthropies and pronounced successful. Although the model was also highly praised by then-minister of health, Dr. Aaron Motsoaledi, inefficiencies and lack of funds within the Gauteng Department of Health prevented implementation on a provincial level.

Legacy

Browde received several special invitations and awards. In 2004, she was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Science by Wits University for achievements in medical and community spheres and was asked by the Vice Chancellor to deliver the speech at the medical school graduation ceremony (at which her granddaughter Emma qualified as a doctor).

On the award of her Honorary Doctorate, Browde was described by the award committee as follows:

Dr Browde has dedicated her life to the promotion of health. She has done this as a cancer therapist and researcher, striving to improve the cures, care and palliation available to patients. She has done it as a politician, working to improve the living conditions that determine the health of the poor. She has done it as a caring human being, spreading the word that suffering can be alleviated, teaching health professionals and supporting … those who face death. She has done it as an activist who has succeeded in changing policies and attitudes.

Browde at times had an uneasy relationship with South African Jewish communal leadership. With her husband, the noted advocate Jules Browde (1919-2016), she often adopted more liberal or progressive stances than the official positions of organizations such as the South African Zionist Federation and the South African Jewish Board of Deputies. Points of disagreement ranged from questions of Israeli state policy to domestic matters such as economic sanctions against the Apartheid state, which Browde supported while many South African Jewish leaders did not.

In her later years, Browde became active in organizations such as Save Israel, Stop the Occupation (SISO), and the international Jewish Democratic Initiative (JDI), which promotes social justice, a peaceful resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and “equality of civil and political rights as envisaged in Israel’s Declaration of Independence.”

In August 2011, Selma and Jules Browde were joint recipients of the South African Jewish Report’s Helen Suzman Lifetime Achievement Award for their devoted contributions to South African political, social, and professional life.

Selma Browde died on December 26, 2023.

Moshe, Jordan. “The woman who lit up Soweto.” South African Jewish Report, June 13, 2019; https://www.sajr.co.za/the-woman-who-lit-up-soweto/.

Romero, Patricia. Profiles in Diversity: Women in the New South Africa. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 1998.

Sakes, David. “Browde, legal and communal giant, passes on.” South African Jewish Report, June 1, 2016; https://www.sajr.co.za/jules-browde-legal-and-communal-giant-passes-on-…

Selma Browde. Interview with Daniel Browde. Johannesburg, December 1, 2018.

Speech at University of the Witwatersrand on award of honorary doctorate: https://www.wits.ac.za/media/wits-university/alumni/documents/honorary-…