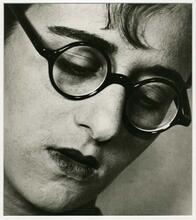

Lotte Errell

Photojournalist Lotte Errell worked tirelessly to make her adventurous travels in Africa, China, and the Middle East accessible to her readers at home in Germany and beyond. Errell’s skills, combined with the rise in popularity of adventure travel and amateur ethnology, allowed her to reach international status. Errell was but one among a large number of European Jewish women who pursued careers in photography during the Weimar era, and she traveled the world throughout the 1930s taking photos and writing essays. She was interrupted in the 1940s by the war. The quality of her reporting and photographs indicates that she would have continued to higher levels had she not been hindered by the Nazis and later by her health and second husband.

Photojournalist Lotte Errell worked tirelessly to make her adventurous travels in Africa, China, and the Middle East accessible to her readers at home in Germany and beyond. Her success illustrates how photography and travel journalism provided women in Weimar-era Germany with new possibilities for earning a living as well as achieving independence in their careers. Errell’s skills combined with the rise in popularity of adventure travel and amateur ethnology to allow her to reach international status. The quality of her reporting and photographs indicates that she would have continued to even higher levels had she not been hindered from continuing her career first by the Nazis’ rise to power and later by her second husband.

Early Life and Career Successes

Lotte Rosenberg was born on February 2, 1903, in Münster, Germany to a wealthy Jewish family. Her mother, Setta (née Wolfs, 1874–1910) died when she was seven years old. Her father, Bernhard (b. 1869–d. Theresienstadt 1942), was a second-generation horse dealer. Lotte attended the Lyceum Annette von Droste-Hülshoff, a Catholic school for girls, from 1909 to 1919. Though she was an autodidact in photography, she also probably gained skills while working for Richard Levy (1899–1992), a Berlin photographer and commercial graphic artist whom she married in 1924. She also took his artist’s name, Errell, which he had formed out of his initials. In 1928, they both accompanied ethnologist Gulla Pfeffer and film director Dr. Friedrich Dalsheim on an expedition to Ghana (then known as the Gold Coast). The resulting film, Menschen im Busch, was shown in Berlin in 1930, while Errell’s photographs were also published in the periodicals Atlantis and Koralle. In 1931 she published these photographs together with an essay in her book Kleine Reise zu schwarzen Menschen. Unlike other travel authors, Errell labored to make her subjects accessible through both photographs and texts. Her tendency to focus on individual people and objects, as well as upon isolated details, can perhaps be ascribed to the technique of her husband, who was among the first to use photography in advertising.

In September, 1931 Errell undertook a trip of over one year to China for the German publisher Ullstein. There she met with important functionaries such as former Chinese Emperor Pu Yi (1906–1967) whom she visited together with French journalist Albert Londres (1884–1932), with whom she had a brief love affair. She also interviewed and photographed women in Chinese high society and wrote about child workers. Her reports from this trip included little about contemporary politics, perhaps because that was a field usually covered by male reporters. Instead, she focussed on the everyday life of different social classes. This was her largest and most widely published project, culminating in 1933 in an exhibition at the Galerie Nierendorf in Berlin. She divorced Levy in March 1933 and the following year travelled to England and Ireland on another assignment. At that time, photography had become a popular career for numerous women because, as a new field, it was not yet dominated by any particular group. However, that Errell was asked to publish essays along with her photographs was quite unusual.

World War II

Errell was but one among a large number of European Jewish women who pursued careers in photography during the Weimar era. After the Nazis came to power, she was in danger of losing her membership in the National Organization of German Writers. Luckily, she received support from a number of German publishers who allowed her photographs to be published anonymously. Two editors of the Associated Press, Leon Daniel and Louis Lochner (1887–1975), also made attempts to assist her in finding work as a journalist elsewhere. As a result of their efforts, she travelled to Iran for the Associated Press in May 1934, remaining there three months longer than planned due to illness. At the end of her trip she accompanied Swedish crown prince Gustav-Adolf (1906–1947) on his official visits to Teheran, Isfahan, and Persepolis. At the end of 1934 she continued on to Northern Iraq and Kurdistan, and prepared for journeys to Afghanistan and Balochistan (present day Pakistan) which she unfortunately never made. On December 7, 1934, the German Press Association finally forbade her to work as a photojournalist in Germany.

Cut off from her source of income, Errell then moved to Baghdad and on April 26, 1935, married urologist Herbert Sostmann, head doctor of the Jewish hospital, who had moved there after having been forced to leave a similar position in Berlin in 1933. By her own account, she worked less as a photojournalist after her marriage because of her husband’s disapproval. However, in the fall she traveled to Kurdistan and Suleimania to interview soldiers and political functionaries. Her increased focus on women from a more sociological perspective is reflected in these photographs, such as the one of female politician Hafza Chan. In 1936 she undertook further travels to Lebanon and Syria and in 1937 to Europe, including Austria and Germany, to visit family. In 1938 she took a three-month trip to New York and Chicago, where she took photographs under contract for Life magazine. At that time both she and her husband attempted unsuccessfully to emigrate to the United States.

At the outbreak of war in 1939, Errell was interned briefly in Iraq as the owner of a German passport, though in 1940 it was stamped with a “J.” On November 27, 1941, she lost her German citizenship entirely. However, her stateless status did not stop officials in Iraq from suspecting her of espionage for Germany and in 1941 she was arrested and soon jailed again as an enemy national. In July 1942 she was turned over to British authorities without being told upon what grounds and was then deported to Palestine, Kenya, and finally to a camp in Uganda; that same year, her father died in Theresienstadt. By 1943, she was in an internment camp in Entebbe, where she found work as a secretary for the government. She was finally released in May 1944, after which she returned to Baghdad, where she remained until the end of the war. Immediately thereafter, she returned to Palestine for a short time and again attempted, unsuccessfully, to emigrate to the United States. In September 1954, both she and her husband returned to Munich, where Sostmann opened a clinic. She finally gave up photography both for health reasons and because her husband disapproved. Herbert Sostmann died in 1981; Lotte Sostmann survived him by ten years and died in Munich on June 26, 1991, at the age of eighty-eight.

Selected Works by Lotte Errell

Kleine Reise zu schwarzen Menschen. Berlin: 1931

Periodicals

Atlantis (Berlin).

Bazar (Berlin).

Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung (Berlin).

BZ (Berlin).

Die Dame (Berlin).

Koralle (Berlin).

Münchner Illustrierte (Berlin).

Uhu (Berlin).

Die Wochenschau (Essen).

Exhibitions

Berlin, Galerie Nierendorf (1933).

Essen, Museum Folkwang (1997).

Berlin, Das verborgene Museum (1998).

Eskildsen, Ute, ed. Fotografieren hieß teilnehmen. Fotografinnen der Weimarer Republik, Düsseldorf: 1994.

Meiselas, Susan. Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History. New York: 1997.

Lotte Errell: Reporterin der 30er Jahre. Katalogue der Museum Folkwang. Essen: 1997.