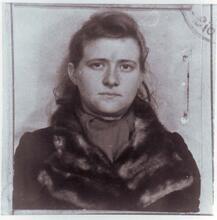

Marilyn Golden

Marilyn Golden was a long-time disability rights advocate. She became involved in disability rights in the 1970s, just as the modern disability rights movement was beginning. Golden served as a senior policy analyst at the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund (DREDF) for most of her professional career, during which time she played a key role in the development, passage, and implementation of many sections of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA). Her advocacy molded and shaped accessible architecture and transportation across the United States and internationally. She was also a strong opponent of physician-assisted suicide.

Family and Education

Marilyn Golden was born in San Antonio, Texas, on March 22, 1954, to Aaron and Clarice (Lerner) Golden. She and her sister Carol grew up in a Reform Jewish community. She attended Temple Beth El and was a leader in the San Antonio Federation of Temple Youth (SAFTY) and the Texas-Oklahoma Federation of Temple Youth (TOFTY), part of the national Reform Jewish youth movement. Through these activities, she honed her skills in bringing people together with fun, purpose, and warmth.

Golden attended Brandeis University from 1973 to 1977, spending her junior year in Israel. While traveling through Switzerland in the summer of 1976, she fell out of a tree as she was climbing back into her youth hostel balcony and sustained a spinal-cord injury that paralyzed her lower body. After undergoing several months of extensive rehabilitation, Golden graduated with a BA in sociology, magna cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa.

Disability Rights Advocacy

Golden’s disability spurred her to focus her social justice lens on disability rights advocacy. In 1977, the modern disability rights movement was just beginning, and Marilyn became one of the movement’s primary leaders and catalysts for change, particularly in the areas of accessible architecture and transportation.

From 1980 to 1988, Golden served as the director of Access California in Oakland. At the time, Berkeley and Oakland were the centers of the modern disability rights movement in the United States. While at Access California, Golden focused on improving accessible architecture and transportation in California, through community activism and drafting and supporting legislation.

In 1988, Golden joined the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund (DREDF). DREDF was then the leading disability rights organization, at the forefront of radical disability politics. Golden ultimately rose to the level of senior policy analyst at DREDF and worked there until her death in 2021.

During her first ten years at DREDF, Golden worked on accessible architecture and transportation across the United States. Through this work, she became a consummate community organizer, as well as a nationally recognized expert on accessible architecture and transportation

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA): 1998-1990

Golden moved to Washington, D.C., for nine months to help advance the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). She played two essential roles during the enactment of the law: lead coordinator of community organizing and substantive expert on accessible architecture and transportation.

Golden and Justin Dart were the officially designated co-leaders of the grassroots efforts to pass the ADA. Golden’s acumen and contacts became the linchpin for that effort. She identified several people in each state who became her ADA regional contacts and ensured that they received the necessary information to help lobby for the ADA from their respective states. She also consistently received information from those contacts that assisted the national strategy. The effective flow of top-down and down-up information is the essential component of community organizing. Golden’s skills and personality ensured this flow of information, allowing members and allies of the disability community to convey their support for the law to members of Congress.

Golden’s second essential contribution arose from her substantive knowledge of accessible architecture and transportation. Over the course of the negotiations on the ADA in the House of Representatives, serious logjams arose regarding accessibility requirements for Amtrak, commuter rail, public buses, and Greyhound buses. Golden’s expertise helped craft successful solutions that ensured accessibility to the greatest extent politically possible. She specifically helped develop the ADA’s requirement that when a building was renovated, an accessible path of travel had to be created to that renovated area, subject to a cost cap, an idea she brought from her work on an Oakland law.

Implementation of the ADA

Following passage of the ADA in 1990, Golden became one of the primary leaders in implementing the law. From 1992 to 1994, she directed the ADA Training and Information Network, a federally funded project that trained and supported a network of 400 ADA specialists with disabilities. She was also the principal author of DREDF’s publication “The ADA: An Implementation Guide,” which provided practical information for both activists and allies.

Most importantly, Golden focused relentlessly on implementing the ADA’s provisions on accessible architecture and transportation. She was a skilled negotiator with the Departments of Justice and Transportation during the development of their regulations and sub-regulatory guidance, on which the ADA’s implementation depended. She ensured the ADA’s effective implementation both through her participation on official advisory groups and boards and as a community organizer.

In 1991, Golden was appointed to the Urban Mass Transportation Administration’s ADA Federal Advisory Committee, advising the Department of Transportation on the development of its ADA regulation. In 1996, she was appointed by President Bill Clinton to the United States Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board (the “Access Board”), on which she served until 2005. The Access Board establishes accessibility guidelines used by all federal agencies across a range of areas. During her time on the Access Board, Golden served on the Rail Vehicle Accessibility Advisory Committee (2013-2015) and the ADA Architectural Guidelines Review Advisory Committee (1994-1996).

In her role as a community organizer, Golden ensured that the Departments of Justice and Transportation heard from the disability community as the agencies developed regulations and sub-regulatory guidance. She did so by deploying her ADA regional contacts and developing new contacts; explaining to these individuals the importance of technical documents from the agencies; providing clear information on what were often complex technical issues; and ensuring that the disability community could effectively communicate its positions to the federal agencies.

In 2014, President Barack Obama honored Golden as a White House Champion of Change in Transportation.

International Efforts

In addition to her work in the United States, Golden served as the Co-coordinator of the Disabled International Support Effort, which provided material aid and technical assistance to disability organizations in developing nations. Her involvement in international disability rights grew following the ADA’s passage. She was called upon to share her disability rights knowledge with audiences and advocates in South Africa, Germany, Austria, New Zealand, Australia, Switzerland, Spain, Costa Rica, the European Union, and Russia, and at the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, China.

Physician-Assisted Suicide

Marilyn Golden on Assisted Suicide Laws at the Disability Rights Leadership Institute on Bioethics, April 25, 2014.

Golden was fervently opposed to laws permitting physician-assisted suicide. Beginning in 1999, she authored several articles arguing that assisted suicide laws represented a dangerous public policy for people with disabilities. In 2014, she played a lead role in conceiving, producing, and leading the Disability Rights Leadership Institute on Bioethics. She worked on many successful campaigns to defeat physician-assisted suicide legislation in states across the United States and represented the disability community in debates and dialogues on the issue.

Golden believed that physician-assisted suicide laws had the potential to abuse people with disabilities, because once someone sought and obtained permission for physician-assisted suicide, there was no way to prevent caretakers from initiating the death without the person’s further permission. Moreover, outside pressures from family, caretakers, or medical staff might cause a person to apply for physician-assisted suicide even if they would not otherwise have chosen to do so. Finally, the realities of the medical system in the United States meant that terminating a life was less expensive than providing effective palliative care and hospice.

Golden was particularly concerned that prejudices about disability resulted in a belief that a person’s life is not worth living after they become disabled. Based on her own experiences after her accident, she knew that most people in such circumstances eventually realize that their lives are worth living even with their disability. Her concern was that physician-assisted suicide as a public policy might cause some individuals with disabilities to choose suicide before coming to terms with their disability.

Israel and Palestinian Rights

Golden vigorously opposed the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza and Israel’s actions with regard to Palestinians. She valued her participation in the East Bay’s Kehilla Community Synagogue, a politically progressive Renewal congregation, partly because she was part of a community whose positions on Israel, Palestinian rights, and the importance of a Palestinian state aligned with her own.

Family and Friends

Golden lived in collective households in Berkeley until she began a relationship with Rabbi David Cooper in the mid 1990s and moved into a house with him. The relationship with Cooper lasted until Marilyn’s death. Golden was the step-parent of David’s children, Talia Cooper and Lev Hirschhorn, and the aunt of Jordi Pollock, Russell Miller, and Adam Miller, all of whom loved her playfully transgressive attitude towards life.

Golden built a community of left-leaning friends and allies who embodied her values. In addition to her participation in the disability community and the Kehilla Community Synagogue, she was an active member of the co-counseling movement.

Marilyn Golden died of melanoma at the age of 67 on September 21, 2021. The legacies of Golden’s life’s work surround us. They are, quite literally, embedded in American infrastructure.

Roundtable of disability rights advocate Marilyn Golden’s friends and colleagues, September 2022.

Click here for a slideshow of photos prepared for Marilyn Golden’s memorial service.

Selected Works by Marilyn Golden

“The danger of assisted suicide laws.” CNN, October 14, 2014; https://www.cnn.com/2014/10/13/opinion/golden-assisted-suicide/index.html.

“Pioneers in Disability Rights and Community Organizaing: An Interview witih Marilyn Golden”; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TB-LHxlnxIg.

National Council on Disability, The Current State of Transportation for People with Disabilities in the United States, 2005