Anna Maria Goldsmid

Anna Maria Goldsmid’s somewhat unusual career in advocacy for Jewish education, especially of women, began in 1839 with a call to British Jewry to increase at-home religious instruction by mothers by providing accessible instructional materials. It ended some 50 years later with a broad appeal for high-quality universal education by well-trained teachers. In between, Goldsmid broke almost every rule for Jewish women of her time. She spoke out on public causes, she did not marry, and she employed male literary forms and spoke on male topics to male institutions. When she died on February 15, 1889, her obituary in the Jewish Chronicle lauded her as one of the most significant women of the Victorian era.

Anna Maria Goldsmid, daughter of Isabel (née Eliason, 1788–1860) and Isaac Lyon Goldsmid (1778–1859), was a translator, lecturer, reformer, pamphleteer, founder of girls’ schools, and advocate of teachers’ colleges. She was a Victorian Jewish advocate of women’s education and Jewish emancipation who also made a name for herself as philanthropist and poet.

Early Life and Family

The oldest of seven children—Francis Henry (1808–1878), Frederick David (1812–1866), Agusta (1815–1838), Rachel (1816–1896), Caroline (1817–1906), Emma (1819–1902)—Goldsmid was born in London in 1805 into a family of wealthy Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazim who consistently broke the established rules in the Anglo-Jewish community yet managed to remain prominent members of it. Her father, Sir Isaac Lyon Goldsmid, was one of the first Anglo-Jewish emancipationists, acting on his own to contact Members of Parliament when he felt that the Board of Deputies of British Jews was moving too slowly to lobby for reforms. Her brother, Francis Henry, was the first English Jew called to the bar at Lincoln’s Inn, wrote influential tracts on behalf of Jewish emancipation in the 1830s and 1840s, and in 1860 became one of the first Jewish MPs. He established the Infant School for the Jewish Poor and the Jews’ College. He was instrumental in helping to bring the German-Jewish Reform movement to England.

Expanding Access to Jewish Education through Translation

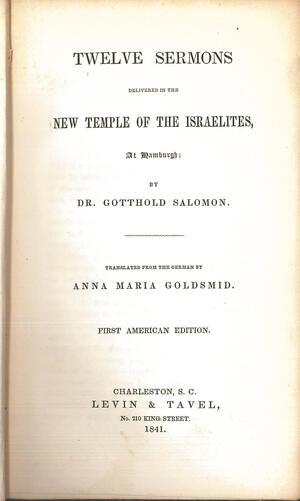

In her early 30s, Anna Maria Goldsmid influenced her brother to establish the Jews’ Infant School, and she herself helped establish the West Metropolitan School for Girls. Her awareness of the lack of Jewish instructional materials probably prompted her to translate the sermons of German-Jewish reformer Gotthold Salomon (1784–1862) into English. In 1839, the act of translation was generally understood to be a male activity in the Anglo-Jewish community, and the idea that a woman could translate religious sermons was deemed especially shocking. Goldsmid justified her transgression in the preface to the volume, saying that the sermons were directed toward “all who are engaged in the formation of the religious character of the young, but above all to mothers, whose especial vocation it is, diligently and lovingly to foster true piety in the hearts of their children.” Since the sermons were to serve as vocational tools for mothers, who were expected to be responsible for their children’s early religious education, it made sense that the translation should be undertaken by a woman. Moreover, “My father, who has acted, both in public and private, on the opinion that religious education can be best conducted at home, shares with me this hope.”

Goldsmid’s appeal to mothers as instructors proved immensely influential, demonstrating to other Jewish women writers of the period, such as Grace Aguilar and Marion Hartog, that it was possible to enter the public world as long as one wrapped oneself in the mother’s mantle. Goldsmid’s translation also had a powerful impact on the development of the Reform movement in England. Soon after she published it, she suggested to her brother that he read one of the sermons before their congregation in St. Alban’s Place, which he did, stirring the first serious reform/orthodox rift in the Anglo-Jewish community. That rift was healed, but two years later the number of families who wanted vernacular sermons was sufficiently large to justify their secession and the formation of the West London Synagogue of British Jews, the first Reform synagogue in England. In his first sermon, David Woolf Marks (1811–1909), the synagogue’s first preacher, repeated Goldsmid’s idea that sermons were useful for home instruction. By 1860, not only the reform, but also the orthodox members of the community were clamoring for sermons. As her obituary put it, “Miss Goldsmid, among the Jewesses of her age, was quite the leader in thought.”

A Public Figure for Jewish Emancipation

Goldsmid followed the reform sermons with numerous translations, including the Development of the Religious Idea in Judaism, Christianity, and Mahomedanism (1855) by the German reformer Ludwig Philippson (1811–1889), Joseph Cohen’s (1817–1899) The Deicides. Analysis of the Life of Jesus and of the Several Phases of the Christian Church in their Relation to Judaism (French, 1872), and the pamphlet, Persecution of the Jews of Roumania (French, 1872). Each one had a significant impact on the community. Goldsmid’s public persona also evolved. In the translator’s preface to Persecution, her persona was a far cry from the meek translator hiding in her father’s shadow. At the age of 67, she spoke instead on behalf of the “whole civilized world”: “While the perpetrators of Jewish wrongs in Roumania shrink not from the committal of the crimes which are here detailed, they do shrink from being held up to the merited execration of the whole civilized world…. I would employ [pen and speech] in order to declare to the Roumans once and for all, that the only course by which they can avoid the censure of mankind, is to cease to deserve it.”

She could carry off this rhetoric because she was herself a well-known figure among both Jews and Christians. She had acquaintance with many of the intellectuals of her day—Crabb Robinson (1775–1867), Harriet Martineau (1802–1876), and Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847)—and regularly corresponded with German-Jewish reformers Leopold Zunz (1799–1886) and Ludwig Philippson. She helped the Hakham (clergyman) of the Sephardic synagogue with his English sermons and was a staunch member of the Anglo-Jewish Association, a literary association almost exclusively open to Jewish men. She worked with Moses Montefiore (1784–1885) to free persecuted Jews around the world. Indeed, one friend told her that she was “really a sort of female edition of Sir Moses.”

Supporting Jewish Women through Philanthropy and Advocacy

Like many wealthy Anglo-Jewish women, Goldsmid endowed charities—the Jews’ Deaf and Dumb Home, the University College Hospital, and the Homeopathic Hospital. Along with seven other “Ladies of the Congregation of British Jews,” she supervised her synagogue’s Charitable Fund. But in other respects, the life path she chose was atypical for Jewish women. She not only pursued the male vocation of translation; she also refused to marry.

Goldsmid was aware of and interested in Jewish women’s issues. In particular, as her work with the West Metropolitan School for Girls in the 1840s indicates, she was devoted to increasing female education. By the 1870s, she was ready to take a bolder step. In April 1874, she was the first woman to be asked to give one of the “Lectures to Jewish Working Men,” a forum sponsored by the Jews’ and General Scientific and Literary Institute, a men’s organization established by a number of the founders of the West London Synagogue some 30 years earlier. Goldsmid’s lecture was entitled “What Jewish girls should learn, what Jewish wives and mothers should practice, and how fathers and husbands should help them.”

In her last years, Goldsmid devoted herself to the national issue of teacher training. She believed there were too few “normal schools,” schools for the training of teachers, to serve the developing national education system. She edited a Prussian educational code as a model for English educational reform, contacted educational reformer Mark Pattison (1813–1884), and endowed a trust with £2000 for a Jewish normal school. However, she died before seeing the fruits of these labors.

Goldsmid’s somewhat anomalous career began in 1839 with a call to increase the level of maternal home instruction by providing vernacular instructional materials. It ended some 50 years later with a broad appeal for credentialed universal education. In between, Goldsmid broke almost every rule for Jewish women of her time. She spoke out on public causes. She did not marry. She employed male literary forms and spoke on male topics to male institutions. After her first translation, she did not give credit for her work to others. And when she died on February 15, 1889, her obituary in the Jewish Chronicle lauded her as one of the most significant women of the Victorian era.

Cohen, Joseph. The Deicides: Analysis of the Life of Jesus, and of the Several Phases of the Christian Church in their Relation to Judaism. Translated by Anna Maria Goldsmid. London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co., 1872.

“Death of Miss Goldsmid.” Jewish Chronicle. February 15, 1889.

Galchinsky, Michael. The Origin of the Modern Jewish Woman Writer: Romance and Reform in Victorian England. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1996, 191-202.

Goldsmid, Anna Maria, to Mark Pattison, October 17, 1876. Bodleian Library MSS Pattison 57.

Goldsmid, Anna Maria, editor. The Educational Code of the Prussian Nation, in its Present Form. London: C. Kegan Paul & Co., 1879.

Ladies’ Committee Proper Establishment of a Ladies Society for the Relief of the Poor to West London Synagogue of British Jews, April 8, 1843.

Leader. Jewish Chronicle. September 23, 1970.

“Lectures to Jewish Working Men.” Jewish Chronicle. April 3, 1874.

Marks, David Woolf and Rev. A. Löwy. Memoir of Sir Francis Henry Goldsmid. Second edition. Edited by Louisa Goldsmid. London: C. Kegan Paul & Co., 1882.

Marks, David Woolf. Sermons Preached on Various Occasions at the West London Synagogue of British Jews. London: A.W. Bennett, 1851.

Persecution of the Jews of Roumania, by a Friend of His Country, His People, and of Liberty. Translated from the French Version of the Original Hebrew. Translated by Anna Maria Goldsmid. London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co., 1872.

Salomon, Götthold. Twelve Sermons Delivered in the New Temple of the Israelites, at Hamburgh. Translated by Anna Maria Goldsmid. London: J. Murray, 1839.