Jewish Women in Screendance

Screendance is a contemporary art practice that focuses on depictions of the body on screen. When Screendance came into maturity in the 1970s, a number of its practitioners were part of both the feminist art movement and the avant-garde filmmaking community, often women and Jewish. This group was largely based in New York and either children of immigrants to the United States or immigrants themselves. Jews were often over-represented in Screendance, as they were in other post-war art movements, and many of the seminal figures in Screendance (also called filmdance, dance for camera, or cine-dance) were Jewish women for whom the field allowed a particular kind of self-expression. It is Jewish women who largely created the field as we know it today.

Introduction

Screendance is a contemporary art practice that focuses on depictions of the body on screen. Often, movement is choreographed for the screen to depict dancing bodies in ways not possible in theatrical spaces. Screendance is an evolving form that has its earliest examples in the first experiments with film technology in the late 1800s and found its modern form around the mid-twentieth century.

What differentiates Screendance from the simple documentation of dance or documentary filmmaking is the intentionality of the use of the camera and editing as a means of creating an otherwise impossible image. The camera may be used to create intimacy with its subject in ways not possible on stage. Editing is often used to create sequences of movement that could not have existed in “real” time and space. And unlike in cinema, there is often nothing but the dancing body on screen through which the entire vision of the filmmaker must be told.

When Screendance came into maturity in the 1970s (though earlier examples exist), a number of its practitioners were part of both the feminist art movement and the avant-garde filmmaking community. Both groups were outsiders, often based in New York and either children of immigrants to the United States or immigrants themselves. Jews were often over-represented in Screendance, as they were in other post-war art movements (such as Abstract Expressionism), due to the circumstances of diaspora and immigration from Europe. Emerging artforms often have few rules or barriers to participation, allowing otherwise marginalized groups to find their creative voices. While the field of modern dance was, in the post-war years, also a place in which Jewish women found space, Screendance allowed for its artists to have complete creative control in a way a dancer in a dance company would not. It was a space yet to be defined, where anything was possible. Many of the seminal figures in Screendance (also called filmdance, dance for camera, or cine-dance) were Jewish women for whom the field allowed a particular kind of expression of freedom and/or a space to tell personal stories, often about immigration or oppression. Thus, it is Jewish women who largely created the field as we know it today. Indeed, Amy Greenfield was one of the first to advocate for screendance as a free-standing art form, untethered to live dance or traditional dance techniques. In her article “Dance as Film” (Filmmaker’s Newsletter, January 1969), she argued for a model of “filmic dance.” In contrast to medium-specific approaches, Greenfield did not see dance and film as incompatible forms, but rather as siblings with a great deal in common: she writes, “Film and dance are the only two art forms that move in both time and space. That is a strong basis on which to form a common language.”

Maya Deren

Maya Deren (1917-1961; born Eleonora Derenkowska) is often referred to as the Godmother of Avant-Garde film. At the age of five, she fled anti-Semitic pogroms in Ukraine, arriving in the United States with her family in 1922. After studying at Syracuse University and New York University, she earned a master’s degree from Smith College. Deren trained in dance and photography and began making films in the 1940s, when it was exceedingly rare for women to do so. While she died at the age of 44, Deren’s body of work, starting with Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), left an indelible mark on experimental filmmaking and, along with her writing, is often cited as a seminal reference point for contemporary screendance history.

Deren’s A Study in Choreography for Camera (1945), featuring Talley Beatty, is perhaps the film that comes closest to a genesis point for contemporary screendance. While Hollywood films of that era featuring dance tended to neutralize the value of the individual, emphasizing instead the importance of the group, or to use dance to simply move the story along, Deren elevated the individual to a place of dignity through her use of camera technique and editing. Deren both humanized and articulated the dancing through surrealist flights of fancy and established a female-to-male cinematic gaze that was completely at odds with the cinematic practice of the era. Her use of the camera to frame and sexualize the male body preceded by decades discussions about gaze theory and the gendering of cinematic space.

A Study in Choreography for Camera broke numerous taboos, transgressed stereotypes, and made a distinctly political statement by featuring an African American man (Beatty) not as a servant or a butler, as Hollywood might have cast him, but rather as a fully formed human being, an elegant and talented dancer and the sole performer in Deren’s four-minute silent film. Deren’s editing amplified the intimacy of the viewer’s engagement with Beatty’s image as we track him through both interior and exterior spaces. Deren used the dancer as the constant in a shifting landscape of place and time, the flow of movement unbroken as location changed from scene to scene, questioning the logic of chronology. In addition to the famous unbroken pan, in which we see Beatty in the forest appearing and re-appearing as the camera seems to turn 360 degrees on its axis, we also see the dancer begin a gesture in one space and continue it in another, seemingly without interruption. In one moment, Beatty moves into a sort of living room where above the mantle we briefly see a framed portrait of Frida Kahlo, a nod to Deren’s own proto-feminist identity. In another moment we see Beatty turning on his own axis as the camera frames first torso, then head, then feet, the turning speeding up as the cuts progress. At moments in Deren’s silent film, Beatty seems suspended in mid-air for an impossible length of time. At other times, an unfolding of the dancer’s arm begins in one location and seamlessly ends in another, the choreography literally “moving” the viewer into another place. Simultaneously she created a work of art in which dance, removed from narrative responsibility, is contingent on neither what precedes it nor what follows it in the frame. Deren thought about film “anagrammatically,” as she explained:

“In an anagram all the elements exist in a simultaneous relationship […] Each element of an anagram is so related to the whole that no one of them may be changed without affecting its series and so affecting the whole. And conversely the whole is so related to every part that whether one reads horizontally, vertically, diagonally or even in reverse, the logic of the whole is not disrupted, but remains intact.” (An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film).

This statement, along with her remarkable work in film, opened the door for generations of filmmakers who built on Deren’s ground-breaking work.

Yvonne Rainer

An inheritor of Deren’s proto-feminist legacy, dance and film artist Yvonne Rainer (b. 1934) is claimed equally by the dance and experimental film communities. Rainer brought a dance aesthetic to such films as Lives of Performers (1972) and Film About a Woman Who (1974); her work is perched on the threshold of a new model, leaving behind the established form of dance and adopting the form of cinema as a space for dance-like activity. Rainer’s black and white film, Hand Movie, made in 1966 while she was bedridden and recovering from surgery, suggested that through cinematic framing, movement could be isolated to one appendage and still engage the language of dance and performance, holding the viewer’s gaze while questioning the form within which it is situated.

Meredith Monk

Meredith Monk (b. 1942), a composer and pioneer in what is now called “extended vocal technique” and “interdisciplinary performance” and a MacArthur Foundation “Genius” Award recipient, creates works that thrive at the intersection of music and movement. Her Jewish heritage and humanist concerns are particularly visible in two groundbreaking films, Ellis Island (1981) and Book of Days (1988). Ellis Island, shot before the restoration of the historic immigration facility, combined dance and performance in a haunting depiction of the immigrant experience.

In Monk’s Ellis Island, a site-specific black and white film, dancers excavate the grounds of a decrepit and as-yet-unrestored Ellis Island, mining it for the memory of the refugees and immigrants who passed through its portals. We see the characters in period dress, undergoing a kind of scrutiny and often humiliation that reminds us of the present-day crisis of other refugee populations. In the film, Monk moves large groups of people across the screen, many of whom are dancers or musicians and singers, and we see a startling kind of diversity in the way she portrays the newly landed immigrants not as a monolithic group but rather as global citizens.

In Book of Days Monk gives us a glimpse into the Middle Ages through a twentieth-century lens. In a medieval ghetto, a child envisions a future of airplanes and television; to the child’s grandfather, they are visions of Noah’s Ark, and the ancient wisdom of the Jewish heritage is transmitted from generation to generation. Again, using dancers to portray some of the characters in her film, Monk choreographs a nuanced language of gesture for the camera that is intimate and heartbreaking and suffering is seen as both random and universal. Created in the years in which the HIV/AIDS crisis greatly affected creative communities, she draws parallels between the plagues of the Middle Ages and those of modernity. Book of Days illustrates Monk’s fluid definitions of identity, genre, and disciplinary boundaries, both in her life and artistic practice.

Amy Greenfield

Amy Greenfield created new ways of seeing bodies in motion on screen with her pioneering work in the 1970s and beyond. In her film Transport (1971), made in the specter of the Vietnam War, bodies—non-responsive, limp as if wounded, in a sense “performing” death—are literally transported over harsh terrain. The active and able-bodied performers carry and rescue the wounded ones, while the hand-held camera provides a shifting point of view, oscillating between first and third person. Raised above the group, bodies fly through the air as if launched by canon fire. It is an image that speaks of both trust and the necessity of saving or preserving the dignity of the damaged ones.

The iconography in Transport, as well as in Greenfield’s Element (1973), is based in the simple and quotidian gestures of the everyday. Greenfield’s films make use of “everyday movement,” so-called by the group of artists and dancers who gathered in the basement of the Judson Memorial Church in New York in the early 1960s to redefine the very nature of dance. Greenfield’s films are noteworthy for their destruction of linearity and the way in which the camera becomes a part of the community of performers on screen. The bodies in Greenfield’s work cannot be read as any bodies; they are specific and recognizable as bodies of an era politicized by war—bodies in crisis. In her film Element (1973), her naked body rises and falls from a sea of black mud until the body and the landscape are inseparable. Unlike in Transport, in Element, no external narrative is present: no literary devices, no juxtapositions of the visual culture of objects or the kind of editing techniques that suggest a narrative outside of the body’s experience with itself and its environment. The use of the close-up to contrast the wide shot in Element is always limited to the body and the site it inhabits. No other signifiers are present in Element; thus we are free to imagine our own metaphors for the engagement of Greenfield’s body to the landscape and her performance within it.

Anna Halprin

Anna Halprin (b. 1920) has been a leading force among Jewish activist dance makers since the mid-twentieth century. She has long worked with filmmakers across a number of genres, some focused on dance made for the camera (Screendance) and in documentary and hybrid projects as well, including the 1970 film The Golden Positions, by West Coast experimentalist James Broughton.

Halprin is well known for her work with disenfranchised communities, including people of color, those living with illness, and intergenerational populations. She has used the wisdom of her own body as a blueprint for what has come to be known as “community work,” a logical outcome of the Jewish principle of tikkun olam, or repair of the world. Halprin performs her commitment to community and to repairing that which is weakened or broken through dance. She has noted that themes from Judaism have influenced her and her work since her childhood:

I remember at age five watching my grandfather praying at shul [synagogue]. He would jump up and down with great energy and joy, throwing his arms into the air as if he were possessed by some higher spirit. With his white hair and long, white beard he looked like God to me, so I thought God must be a dancer. This experience gave me the image of dance as something special, and inspired me to spend my life looking for a dance that would mean as much to me and others as my grandfather’s dance meant to him (Jews Are a Dancing People).

This memory was the basis for Halprin’s The Grandfather Dance, originally choreographed for the stage, which premiered on February 2, 1994, at San Francisco’s Fort Mason Theater. Halprin dedicated the dance to her grandchildren as a way of helping them understand their heritage. The dance was subsequently the basis for the film My Grandfather Dances (directed by Douglas Rosenberg, 1996), which was awarded the Director’s Prize in 1999 at the International Jewish Video Competition at The Judah L. Magnes Museum in Berkeley, CA.

Sally Gross

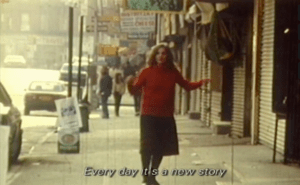

Sally Gross (1933-2015) was a New York-based choreographer and performer who had a dynamic presence in the dance world for over 40 years. Born and raised in the Lower East Side of New York City during the late 1930s and 1940s, she was the last of eight children born to a Polish-Jewish immigrant family with little money and often helped her father sell fruit and vegetables from a horse-drawn wagon. As a native Yiddish speaker, she acted as a translator for her parents, who hardly spoke any English. Gross was an original member of New York’s renowned Judson Dance Theater during its highly influential history between 1962 and 1964. Gross was featured in films such as Robert Frank’s Beat Generation masterpiece Pull My Daisy (1959), and she made a number of experimental films based on her improvisational dance technique. Of special note is her short film Mameloshen (directed by Josh Blum, 1983), in which we see Gross improvising on the sidewalks of the Lower East Side in New York City, inserting herself into the quotidian life of the Jewish neighborhood where her father ran an illegal pushcart. As she moves through the space where both she and her father had inscribed their presence, she speaks in her Mameloshen—her mother tongue of Yiddish. Gross was clearly weaving together her modern self with her Jewish self, imprinting both onto the very streets where she minded her father’s pushcart as a child. Scholar Benedict Anderson points out that language is what ultimately creates a sense of shared identity. In the film, Gross speaks simultaneously in two languages, dance and Yiddish, thus bridging two communities and two histories. Body language, the language of food, the taste on the tongue, the language of hair and gesture, dance and the spoken word all conspire to create a sense of belonging. For Jews in the post-war era, such public gestures of identity could be fraught, as it was not yet clear where Jewish identity fit in the evolving cultural landscape. And of course, the specter of the Holocaust still hovered slightly out of the frame.

Ellen Bromberg

In 1989, the San Francisco Bay Area PBS affiliate, KQED, commissioned a group of dance and performance artists to create work for television broadcast for a landmark series called “Dancing From The Edge.” Ellen Bromberg, whose long career as a dancer and choreographer was well-known in the Bay Area, was invited to translate her stage work, The Black Dress, to the screen. The Black Dress took its name from a painting by Alex Katz and featured an all-woman cast. The resulting film was both haunting and emotional in its portrayal of grief and anxiety and for its breaking of the fourth wall of the television screen as the dancers exit through the frame of the camera.

By 1996, Bromberg had begun to focus on work at the intersection of live performance and media, creating work for the screen and collaborating with other choreographers and media artists to make immersive multi-media dance projects for the theater. As an Artist in Residence at the Institute for Studies in the Arts at Arizona State University, she created the collaborative work Falling to Earth. A multi-media performance piece created specifically for the Intelligent Stage, Falling to Earth combined interactive media, video, and live performance and was presented at the International Dance and Technology Conference at ASU in 1999. The immersive project used nascent digital and analog technologies to create a visual landscape that framed live dance and spoken text.

In 2000, Bromberg collaborated with video artist Douglas Rosenberg on a project called Singing Myself a Lullaby. The project began as a multi-media work for theater that followed the end of life of choreographer John Henry, from HIV/AIDS, and received the Isadora Duncan Dance Award. They subsequently created a documentary based on the project, funded by a grant from The Project on Death in America and produced by Wisconsin Public Television, which was broadcast nationally on numerous PBS affiliates.

As an activist for the field of Screendance, Bromberg is well known for her work as a filmmaker, curator, media artist, and writer. Her essays have appeared in a number of print and on-line publications, including Envisioning Dance on Film (Routledge), Extensions: The On-line Journal for Embodied Technology, and the Interdisciplinary Humanities Journal. During her long career as a professor at the University of Utah, Bromberg created the first Certificate in Screendance and was also the founding director of the long-running and influential International Dance for the Camera Festival.

Silvina Szperling

Silvina Szperling (b. 1960) was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She trained in dance from an early age and began choreographing in the 1980s. She has been a driving force in bringing Screendance to Argentina and elsewhere in the southern hemisphere. Her own early projects, including the award-winning film Temblor, have made her well-known outside of Argentina as well.

Szperling is Founding Director of the International Festival VideoDanzaBA, a video-dance festival that has taken place since 1995. The festival has attracted an international community of artists working in the genre of video-dance. As a founding member of a number of Screendance advocacy organizations (Videodance Mercosur Circuit, Brazilian dança em foco, Uruguayan FIVU, and the Latin American Forum of Videodance), Szperling has mentored generations of students and practitioners into a global understanding of the field. As a student of the history of experimental film and dance in Argentina, she has bridged a generational shift in both dance and media, keeping their histories alive through writing, teaching, curating, the creation of her own work for screen.

Szperling has been an activist for both the representation of Screendance in Argentina and the histories of Jewish-Argentine dance and Screendance. In her presentation at the 2018 Jewishness and Dance Conference at Arizona State University, “Jewish Argentine Princess (The Sequel): A possible Point of View about Jewish Choreographers and Dance Teachers in Argentina,” Szperling laid out a narrative that illuminates the diaspora of Jewish women who brought dance to Argentina. In the version of the talk published in 2019 in Israel’s Dance Today, she noted that although the majority of Jewish immigrants came to Argentina from Eastern Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Jewish presence in Argentina dates back to the early sixteenth century, when Sephardi Jews fled Spain and Portugal because of the Inquisition. Silvina Szperling is both a part of that diaspora and an important figure in the global world of Screendance whose multi-disciplinary approach to the field has made a lasting contribution to how we think about the politics of representation and global politics generally, both in and out of the art world.

Victoria Marks

A number of Jewish artists are making Screendance a vibrant space of discourse in the current era, leading the field into the present while extending the concerns of diasporic Jewishness. Among them is Victoria Marks, a choreographer and Professor in World Arts and Cultures at UCLA, who has, since the 1990s, been creating poignant works for the screen that at their core represent Jewish themes of inclusion and righteousness. Marks’ work speaks eloquently about social justice, disability/ability, empathy, and compassion through what she has called “choreo-portraiture.” In a 2015 interview published in the International Journal of Screendance, Marks spoke about her Screendance work in the context of inclusion and representation on screen while working on a film called Outside In. She states,

I was making a 13-minute film for broadcast, and…I was working with an “integrated dance company,” a group of dancers who were physically disabled and non-disabled. The opportunity, I felt I had, was to change the way disability is thought about in 13 minutes. Now, I know that's absurd, but it's also a great call to what choreography could do….I think I really wanted to look at it as a choreographic and cinematic enterprise…. [B]ecause of that piece, I began to think that there was a way to enter into making things that wasn't so much about “Here's the idea that I have,” as much as to say “‘Let me listen very carefully and think about the ways in which you are interacting and the ways in which you wish to be represented, set alongside the ways in which I see you.” So, not necessarily consciously, that changed a great deal of my work, which I started calling choreo-portraiture.

In such film projects as Outside In, Mothers and Daughters, and Men, as well as her work with returning soldiers dealing with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in Veterans, Marks uses the screen to tell intimate visual narratives that are truthful and moving works of art, speaking to ideas of healing and diverse community. Marks’ work is social justice in action, embodying Jewishness and the idea of doing A biblical or rabbinic commandment; also, a good deed.mitzvot through the art of Screendance.

Blaetz, Robin, ed. Women’s Experimental Cinema: Critical Frameworks. Duke University Press, 2007.

Deren, Maya. An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film. Younkers, NY: Alicat Book Shop Press, 1946.

Deren, Maya. “Notes, Essays, Letters.” Film Culture 39 (1965).

Halprin, Anna. Jews Are a Dancing People, Experiments in Environment. The Halprin Workshops, 1966-1971, Jason Herrington),

“Mobilizing Subjectivity: an Interview With Victoria Marks.” International Journal of Screendance Vol. 5 (2015)

Nichols, Bill, ed. Maya Deren and the American Avant-Garde. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Rosenberg, Douglas. Screendance: Inscribing the Ephemeral Image. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012

Ross, Janice. Anna Halprin: Experience as Dance. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008.