Juedischer Frauenbund (The League of Jewish Women)

Founded in 1904 by Bertha Pappenheim, The League of Jewish Women pursued secular German feminist goals while maintaining a strong sense of Jewish identity. The fight for political power within the German Jewish community was long and arduous – the League criticized the second-class status of women in Judaism, asked for an open discussion of Jewish prostitution, and demanded employment opportunities, which it saw as essential to women’s economic, psychological and emotional independence. It supported vulnerable women through practical social reforms such as setting up outposts for women traveling alone and establishing a shared home for mothers of “illegitimate” children. Despite backlash, the League had a total membership of 50,000 by 1929. The League was dissolved by the Nazis in 1938. In 1953 eighteen women’s societies joined together to reestablish the League.

Approach to Feminism & Jewish Identity

The League of Jewish Women (Jüdischer Frauenbund, or JFB) founded in 1904 by Bertha Pappenheim, attracted a large following. Absorbing some traditional Jewish women’s charities and building on programs that Jewish women’s groups had pioneered, the JFB offered a feminist analysis and approach to social welfare. Combining feminist goals with a strong sense of Jewish identity, it was the first nationally coordinated organization to promote German-Jewish women’s interests. Its membership in and support of the goals of the German bourgeois women’s movement distinguished it from other Jewish women’s organizations of its time as well as from the major Protestant and Catholic women’s organizations.

Despite the considerable tensions involved in being both feminists and conscious Jews, the JFB was unwilling to focus on secular feminism in Germany to the neglect of its Jewish roots. Nor was it willing to focus only on the goals decided upon by the male leadership of the Jewish community, but insisted on fighting for women’s equality in Jewish and secular spheres. Its position as a Jewish organization reflects in microcosm a more general dilemma which profoundly touches minorities even today: the desire for equality while guarding their own distinctiveness. Moreover, its position as a women’s organization highlights an agonizing dilemma of minority women’s groups: whether to “stand by” their men—often accepting women’s second class status within the minority group—or fight their already embattled men for equality.

Allegiance to the JFB was a product of class and age. Its members reflected the overwhelmingly middle-class position of German Jews. Most were housewives engaged in volunteer activities. The feminism of the JFB was shaped by the tensions between its members’ needs for independence and their attachment to traditional “feminine” values, especially a notion of “separate spheres,” the complementarity of men’s and women’s roles and status in society. Thus, while direction came from above, restraint came from the grassroots. The leaders hoped to strike a balance between their feminism and the attraction of a mass base, modifying their feminism in order not to alienate their more tepid following. As a result, the League did not subscribe to a radical version of feminism: instead, it accepted the conventional view that fundamental, natural differences existed between the sexes.

Social Feminism

The League’s activities focused on: strengthening community consciousness among Jews; furthering the ideals of the bourgeois women’s movement; expanding women’s role in the Jewish community; providing women with career training; and fighting the traffic in women.

Within the Jewish community, the JFB’s demand for suffrage and equal representation (not only in the nation, but inside the Jewish community itself), its open discussion of Jewish prostitution and involvement in the traffic in women, its denunciation of the double standard of morality, its criticism of the “second class status” of women in Judaism, and its demand for employment opportunities for women often caused irritation. Anti-feminists attacked the JFB and rabbis ignored it, but it continued to expand to encompass thirty-five thousand women in its first ten years. By 1929 it counted 430 affiliates, 34 of its own branches, 10 provincial alliances and a total membership of 50,000 (more than 25 percent of German-Jewish women over the age of thirty).

The League’s particular emphasis on women’s condition and women’s equality gave form and content to what might otherwise be perceived as simply social welfare projects. It emphasized “social feminism”—practical social reforms to improve the circumstances of women’s lives.

The JFB joined national and international feminist crusades to abolish state regulation of prostitution and condemn the double standard. It brought a feminist analysis to bear on the causes of prostitution. Its leaders also focused on the economic causes of prostitution, arguing that women needed better employment opportunities. Moreover, Pappenheim assailed women’s legal status in Judaism as a special cause of Jewish prostitution. In an era of war and emigration many men left home and never returned. Their wives remained “anchored wives” (agunot), unable to remarry without an official Jewish divorce (which requires that husbands officially divorce wives and not the other way around) or Jewish witnesses to the husband’s death. Hence, Pappenheim claimed that Jewish divorce laws added to the problem of destitution and the traffic in women.

The attempt to end Jewish participation in the traffic in women had feminist and Jewish social welfare components. To protect girls, the JFB, along with Protestant and Catholic women’s groups, set up railroad and harbor outposts for women traveling alone, offered food, hostels and aid to needy young women or female travelers, and organized girls’ clubs, evening recreation and courses for young women in Germany. It supported vocational and educational institutions for Jewish girls in Eastern Europe, sent teachers and nurses there, and published leaflets and warnings on the dangers of traveling alone or accepting job or marriage offers from abroad. While these were clearly social welfare efforts, they were also intended to improve the position of women in society.

The League also established the first home for unwed Jewish mothers in Germany. The Home for Endangered Girls at Neu Isenburg was probably its most radical effort, inspired, most likely, by the radical League for the Protection of Motherhood and Sexual Reform (Bund für Mutterschutz). “Proper” society—both Jewish and Christian—condemned unmarried mothers of “illegitimate” children. The JFB’s Home, established in 1907, protected and educated these women and children, according to Pappenheim, to save them for the Jewish community. She wanted to establish a “home” for girls, not an institution for inmates. Divided into family units where mothers took care of their own babies, the residents received job training and ran the Home themselves. They cooked according to Jewish dietary laws and celebrated all religious holidays together. “Graduates” were placed in jobs upon leaving.

Goals & Priorities

As feminists, the JFB supported career training for women, setting up employment offices, vocational guidance centers, evening courses to improve job skills and several schools (offering courses in the traditional female fields of home economics, child care, basic health care and social work). Challenging the attitude that a woman’s place was only in the home, jobs were seen as a means to economic, psychological and emotional independence. Moreover, the JFB invested in women’s feminist education. Its local and regional associations offered courses on topics such as women and politics, women and the law, or Jewish women in German social work.

The Frauenbund’s most frustrating campaign, to achieve full equality for women within the Jewish community, was part of the larger struggle for women’s suffrage in Germany. Of all its efforts, the fight for political power in the Jewish community was its longest and most arduous, ending well after World War I, when German women had attained suffrage. Pappenheim personally approached numerous rabbis, seeking favorable interpretations of Jewish law regarding women’s rights. Even after receiving a justification from an eminent rabbi, the JFB had to petition and lobby countless individual Jewish communities and organize public meetings and protests. Due to religious opposition women continued to have to fight for a voice, but by the end of the 1920s they had achieved the vote in six out of seven of the major cities (containing over half of all German Jews). Thus, the majority of Jewish women were enfranchised not only in the German nation, but in their own Jewish communities as well.

Beyond these major campaigns, the JFB built or supported tuberculosis care, youth homes, old-age homes, children’s health and vacation facilities, and sanitaria. It supported the German women’s movement’s efforts to revise marriage laws, recognizing that women had become more independent due to their better educations and careers, but that marriage remained autocratic. The JFB also called on women to defend the rights of all mothers, even the unwed. This was probably its most radical challenge to the norms of its community. Moreover, the League tried to make women proud of their own accomplishments. Its newsletter, the Blätter des Jüdischen Frauenbundes, printed articles on early Jewish feminists, on historically prominent Jewish women, and on contemporary female artists and literary figures. It regularly carried reviews and articles intended to raise women’s consciousness.

World War I, the Weimar Republic, & the Shoah

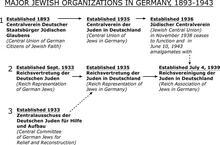

During World War I, the JFB joined the National Women’s Service (Nationaler Frauendienst)—the largest women’s project in the history of the German women’s movement—specifically established to mobilize the home front. The League (and other Jewish women’s organizations) offered the National Women’s Service their institutions, centers and offices, as well as the work of their members. During the Weimar Republic, the League continued its programs but also attempted to fight rising antisemitism. It met with colleagues from the German women’s movement in an attempt to educate German women about Jews and Judaism.

With the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, the League resigned from the Federation of German Women’s Associations. Between 1933 and 1938, it joined other Jewish organizations in a struggle for survival. The League attempted to: prevent the disintegration of communal organizations; ensure the continuation of Jewish practices; help needy Jews; and prepare people for emigration. It aided in the collection of money, clothing and fuel for needy Jews; offered a housewives’ assistance program; wrote its own cookbook for Jews who had difficulty buying kosher meat after Hitler forbade ritual slaughtering; and prepared women for emigration, worrying that they were not emigrating at the same rate as men. The League continued until the Nazis dissolved it after the November Pogrom (Kristallnacht, November 9–10, 1938). Many of its leaders were deported and murdered in 1942.

Post-World War II

Almost fifty years after its initial establishment and fifteen years after its enforced disbanding Jeanette Wolff, Lilli Marx and Ruth Galinski and their colleagues resuscitated the organization. By the end of the 1940s a number of women’s societies and groups had been set up, including one in Berlin, established in 1947, and another in Düsseldorf, established in 1949. Their aim was to support those in need of aid and to further social contacts among Jewish women. In 1953 eighteen revived or newly established women’s societies joined together to create the Jüdischer Frauenbund. In 1956 the JFB had approximately 1700 members and by 1963 it already comprised twenty-four women’s societies. Wolff, Marx and Galinski were among the members of the first executive council. The JFB is a member of both the International Council of Women (since 1954) and of the Deutsches Frauenrat (Council of German Women).

From 1956 to 1980 the JFB published an independent information bulletin, Die Frau in der Gemeinschaft (Women in Society), which contained reports honoring JFB’s work prior to the Shoah and its pre-war activists, as well as reports on current activities, ICJW conferences and the work of its various member groups. It also published articles on politics in general and on women-related topics.

The reestablished JFB consciously related to the traditions of its predecessors. One of its major tasks was the provision of social welfare, especially aid for Holocaust survivors. In this the JFB cooperated closely with the Zentralwohlfahrtsstelle der Juden in Deutschland (ZWST, The Central Social Work Foundation for German Jews), founded in 1917 by Bertha Pappenheim and others. Other major activities were dedicated to education and involvement with Israel.

At present the JFB has approximately 4,000 members. Women’s groups have recently sprung up in the newly-established Jewish communities of what was previously East Germany. The major goals now are integration of newcomers from the former Soviet Union, who currently constitute a majority of the communities’ membership. Together with ZWST, the JFB regularly operates Integration Seminars. Individual member societies offer courses in Judaism as well as in German language and also collaborate with the respective Jewish communities in providing social welfare for the newcomers. As the JFB itself puts it, the women cook and bake for kiddush, organize family celebrations and provide the Passover seder. Since 1996 JFB has again published a bulletin entitled Chaweroth: Blätter des Jüdischen Frauenbundes. However, its contents do not compare with those of its predecessor, Women in Society.

“Jüdisch-sein, Frau-sein, Bund-sein: Der Jüdische Frauenbund 1904-2004.” Ariadne: Forum für Frauen- und Geschlechtergeschichte (2004), 45-46. In H-Soz-Kult, 6/25/2004. www.hsozkult.de/journal/id/zeitschriftenausgaben-1509.

Kaplan, Marion. The Jewish Feminist Movement in Germany: The Campaigns of the Jüdischer Frauenbund, 1904—1938. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1979.

Schwermer, Dagmar. “No Trace of a Salon: The Jewish Women’s Union after 1945.” Bet Debora Journal 2 (2001): 22–23.

Wobick, Sarah E. “Mädchenhandel between Antisemitism and Social Reform: Bertha Pappenheim and the Jüdischer Frauenbund.” In The Sophie Journal 1, no. 1 (2011).

100 Jahre Jüdischer Frauenbund in Deutschland 1904–2004: Ein Jahrhundert Arbeit des Frauenbundes. Published by JFB. Berlin: 2004. Accessed at http://www.juedischerfrauenbund.org.