Miriam Katin

Miriam Katin is best known for her multi-award-winning Holocaust memoir, We Are On Our Own, which portrays her remembered and reconstructed memories as a toddler, hiding in the Hungarian countryside during the Nazi invasion. Katin later moved to Israel, where she served in the Israeli Army. She now lives in New York City, considering herself American, with work featured in the 2007 and 2014 volumes of The Best American Comics. Her published comics include “Eucalyptus Nights,” tracing her time in the Israel Defense Forces, and her second graphic novel, Letting It Go, about her return to Berlin. As the title of the latter suggests, this is a work of release.

We Are On Our Own (2006)

Miriam Katin was born in July 1942 in Budapest, Hungary. During the war years, her father served in the Hungarian army and her mother had to navigate survival for her daughter and herself, under Nazi rule. These years are documented in Katin’s first graphic novel, We Are On Our Own. Katin produced the work while in her early sixties and it was almost never made—she created it despite her own initial prejudices towards both the subject and the format. Katin was ambivalent about making a contribution to the world of Holocaust memoirs: “I thought who needs another Holocaust book anyway?” (Aarons, 2019: 18). Even though she had worked as an illustrator for Walt Disney Animation Studios, Nickelodeon Animation Studio, and MTV Animation in the 1990s, she was unfamiliar and uncomfortable with comics that addressed serious subjects: “The first time I noticed Maus [Art Spiegelman, 1986], it was in a bookstore in Tel Aviv. […] I was so appalled that someone presented this subject in comics form, I did not even want to touch the book” (Baskind, 2010: 240). Fortunately, her attitude later changed: “[L]ater in New York I did read it [Maus] and realized how great it is and that it gave me license to deal with the subject myself” (Baskind, 2010: 240).

We Are On Our Own was published in English (2006), French (2006), Spanish (2007), German (2007), Swedish (2012), Korean (2103), and Polish (2014). It was recognized with top awards, winning the ACBD Prix de la Critique (2008) and an Inkpot Award (2007). The book design is unusual, with a black cardboard cover, an image framed in the front, and off-white pages. This makes the volume resemble both a well-read bible and an old, weathered children’s book. These are important clues to the content and character of a book in which faith is questioned and childhood revisited and re-imagined. In this autobiographical graphic novel, Katin is “Lisa” and her mother is “Esther Levy,” and We Are On Our Own is what Susan Rubin Suleiman would describe as a “1.5 generation memoir,” with Lisa fitting the category of a Holocaust survivor who is too young to have her own clear memories (Suleiman, 2002: 277; see also Aarons, 2019: 21). One poignant example of this is when Esther Levy is forced to have sexual relations with a Nazi officer. The officer slyly bribes young Lisa with chocolate, as she sits outside the bedroom. After her delicious treat Lisa misunderstands the situation, and her mother’s unhappiness: “Why is Mommy crying every time the nice man goes away?” (Katin, 2006b: 43).

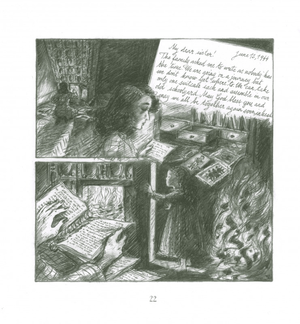

Other elements in the structure of We Are On Our Own remind the reader of the journey of memory through the splitting of time, braiding past (in grey graphite) with present (in coloured pencil). There is Lisa in New York, with her newborn child wrapped in a green blanket, and, later, a series of episodes as her son grows up, in a green playroom and among golden leaves on a green lawn. Then there are Lisa and Esther, drawn in dark and heavy graphite, with only small areas of white, as they dress as Christian peasants and survive bombings, a snowstorm, and the mass rapes by the Red Army. Katin’s choice of materials reflects the emotional memories, from joy to pain and horror. Another Holocaust comic created in pencil, Yossel by Joe Hubert, is an imagined story of a talented fifteen-year-old boy who grows up in Poland under Nazi rule and both draws and participates in the last days of the Warsaw Ghetto. Hubert’s and Katin’s books of drawings suggest immediacy, an element of ongoing work, and the unresolved processing of memory and trauma, with none of the polish of inked comics (see Jennings, 2003).

Katin describes how she was inspired by the work of Käthe Kollwitz, a German artist who lost a son and a grandson through war and whose work often focused on the suffering and tragedy inflicted by conflict (Baskind, 2010: 241). Kollwitz’s devastating images of rape are unlike the celebratory and heroic images from art history by male artists. Equally, Katin’s drawings of her mother and the Red Army not only show the fear and agony of the victims but also reflect on another aspect of Holocaust trauma—the shame felt by rape survivors. Esther frequently cannot articulate to her husband and daughter her experiences of forced sexual relations, mass rape, and the resulting abortion: “It reminds me of that day and that village,” “bad, bad things” (Katin, 2006b: 70, 117).

Kollwitz and Katin also share an approach to expressionistic mark making that reflects the trauma of the memories. Budapest, “a city of beauty and elegance,” is drawn with care and delicacy, with Katin herself describing how “the soft earlier pages represent the memory I have […] and the romance I still feel toward it” (Baskind, 2010: 241). The violent scenes, including the group rape scenes and the shooting of the dog, are portrayed with direct energetic lines, rough with emotional outburst, violence, and anxiety. Katin reveals that “this book really sort of spilled out of me, like a vomit or a diarrhea” (Baskind, 2010: 241).

“Eucalyptus Nights” (2006)

In 1957 Katin moved to Israel. She studied graphic arts and worked as a graphic artist when she joined the Israeli Army. Katin makes the trajectory from Hungary to Israel in her life very clear: “I consider my service in the Israeli Army as my real education” (Katin, 2006b: np). “Eucalyptus Nights,” published in Guilt & Pleasure (2006), reflects on racism and romance in the Israeli Army in the 1960s and is a partial coda to We Are On Our Own. The four-page comic describes Katin’s experiences as a soldier and also a failed love affair with Obadiah, a soldier from Morocco. There are numerous thematic links between We Are On Our Own and “Eucalyptus Nights”—including the suggestion of sub-classes with regard to the Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardi soldier and the references to the Holocaust, through the tattooed numbers on the superior’s arms. In Hungary, Lisa is powerless, but now in “Eucalyptus Nights,” as an Israeli soldier, she has a gun and she wears a similar garb to those who, in Europe, had caused her to live in fear and on the run. As a woman and as a Jew, she is now in a position to defend herself and other Jews.

Katin’s service in the Israeli army was an important and positive part of her life. However, this redemptive narrative has for its background a country whose national policies are propelled by trauma, much like Lisa’s own experiences, and reminders of her previous experiences of sexual abuse are displayed through visual hauntings. The older Lisa/Katin is present in the world of the Israeli Army yet is still acting out her trauma, as a young woman who is a physically fit, yet also damaged, survivor. On the third page of “Eucalyptus Nights,” a Greek prostitute is dancing for Lisa and her comrades, but they are interrupted by other soldiers including Obadiah (Katin, 2006a). The Israeli soldiers mirror the scene with the Red Army, and the drawn figure of the Greek prostitute resonates with the partially unclothed Esther Levy and reveals just how much the past continues to interrupt Katin’s present (Katin, 2006b: 55, 60).

Letting It Go (2013)

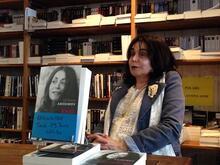

Testimony from cartoonist and Holocaust survivor Miriam Katin, part of the USC Shoah Foundation’s Visual History Archive.

In 1963 Katin moved to New York with her husband, Geoffrey Katin. She worked as an animator at Walt Disney Animation Studios, Nickelodeon Animation Studio, and MTV Animation. She had no intention of returning to Eastern Europe. Her son, however, wanted to apply for Hungarian citizenship so he could live in Berlin, and at the same time her artwork was being exhibited in Heroes, Freaks, and Super-Rabbis at the Jewish Museum, Berlin, in 2010. These events caused her distress, and her response to her son was: “Over my dead body they wanted us dead!” (Katin, 2013: np). Eventually Katin decided to attend the opening of the show, and sign the documentation for her son, and her experiences form part of her second graphic novel, Letting It Go. In 2013, Letting It Go was nominated for an Ignatz Award for Outstanding Artist, and it has been translated into French (2014).

Letting it Go is very embodied and visceral, from our seeing Katin go to the bathroom, having diarrhea, and finally to the bedbugs that bite her in the hotel room, as Katin records her rethinking her own prejudices. Maureen Burdock notes that Katin draws these insects as “rather adorable German bedbugs carrying briefcases and umbrellas, a humorous reversal of genocidal characterizations of human beings as filthy vermin” (Burdock, 2020). The object of Katin’s prejudice has now become bug size—but though small, they are still powerful. Although these creatures look ridiculous, Katin’s thoughts have come, literally, back to bite her. Her body not only now forms part of the bedbugs, but in turn these insects have changed her, much like the visit to Berlin necessitated an evolution of her previous convictions.

Taken collectively, Katin’s publications form an extended narrative of a Holocaust survivor, drawing, revisiting, and releasing the past. Letting It Go is illustrated on the front cover with a balloon—this light humor reflecting both a new relationship with Germany and the personality of the author herself: “Katin's approach to herself, is both charming and inspiring […] The way she makes fun of herself for so many of her fears while still being unable to resist playing them up makes this memoir unexpectedly hilarious” (Clough, 2013).

Aarons, Victoria. Holocaust Graphic Narratives, Generations, Trauma and Memory. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2019.

Baskind, Samantha. “A Conversation with Miriam Katin.” In The Jewish Graphic Novel, Critical Approaches. Edited by Samantha Baskind and Ranen Omer-Sherman. 237–243. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2010.

Burdock, Maureen. “Shapeshifters: Metamorphosing Transgenerational Trauma through Comics.” Unpublished. (2020)

Clough, Rob. “Letting it Go by Miriam Katin.” The Comics Journal, April 4, 2013. http://www.tcj.com/reviews/letting-it-go/. Accessed June 2, 2020.

Jennings, Dana. “Paper, Pencil and a Dream.” The New York Times, December 14, 2003. http://www.nytimes.com/2003/12/14/nyregion/paper-pencil-and-a-dream.html. Accessed 6, May 2020.

Katin, Miriam. “Eucalyptus Nights.” Guilt and Pleasure, Spring, 2, no: 7–8 (2006a).

Katin, Miriam. We Are On Our Own: A Memoir. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly (2006b).

Katin, Miriam. Letting It Go. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly, 2013.

Kubert, Joe. Yossel April 19, 1943. New York: iBooks, 2003.

Spiegelman, Art. Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, My Father Bleeds History. New York, Pantheon, 1986.

Suleiman, Susan Rubin. “The 1.5 Generation: Thinking about Child Survivors and the Holocaust.” American Imago, 59, no:3 (2002) 277–295.