Vitka Kempner-Kovner

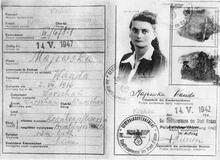

Women played an unusually prominent role in the Jewish underground in German-occupied Eastern Europe. Pictured here are three of the important leaders of the resistance in the Vilna Ghetto (L to R): Zelda Nisanilevich Treger, Rozka Korczak-Marla and Vitka Kempner-Kovner.

Institution: Yad Vashem, Jerusalem

Vita Kempner-Kovner was born in Poland in 1920 to a liberal family and was the first woman to join the Revisionist youth movement Betar. When the Germans invaded Poland in 1939, Kempner left her parents and escaped to Vilna, Lithuania, with her younger brother. After the Soviets lost control of Vilna, Kempner became an active member of the underground resistance movement and was able to move in and out of the Vilna ghetto to relay information to her comrades. Kempner acted as an armed resistance leader and, following the liberation of Vilna in 1944, she was awarded the highest badge of courage in the USSR. After much struggle, Kempner was finally able to immigrate to Palestine in 1946 and lived on Kibbutz Ein ha-Horesh. She later received her degree and psychology and worked as the psychologist for the Kibbutz the rest of her life.

Political Uprising

Vitka Kempner was born on March 14, 1920, in the county-town of Kalisz (Kalisch), western Poland, one-third of whose population was Jewish. Her parents, Hayyah and Zevi, ran a retail business. Her large tribe of grandparents, uncles, and cousins were liberal both in outlook and in lifestyle. At home they spoke Polish, not Yiddish. Kempner, who studied at a progressive Jewish school, was independent from her early years, working for her living even at a young age. The first woman to join the Revisionist youth movement Betar, she took pride in belonging to a militarist group. Only in the twelfth grade did her friends convince her to transfer to Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir. Upon the completion of her studies in the gymnasium, she moved to Warsaw, where she studied in a seminary for Jewish studies. As a student, she joined Avukah, a student movement affiliated with Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir, and was active mainly in the intellectual sphere. Proud of both her Jewish and her Polish identity, she did not find belonging to an elitist group at all problematic.

Fleeing Poland

At the time of the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, Kempner was staying in Kalisz. Once she witnessed the brutality of the SS and their abuse of Jews, she determined that she would “not be humiliated.” She left her parents and escaped to Vilna together with her younger brother Baruch (b. 1923) (whom their grandfather had brought back from Lodz), and many other Jewish youngsters. Vilna, which was then a free city, served as a gathering place for the members of the Zionist youth movements who were searching for routes of immigration to Palestine. The occupation of Vilna by the Soviets in June 1940 led to ideological arguments among the members of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir on the issue of identification with the USSR. Finally, the youngsters went underground and, adhering to the principles of cooperation, made their living by work in fields and in factories.

Underground Movement

Persecution of Jews began soon after the German occupation of Vilna on June 24, 1941. At a time of arrests and the mass murder in Ponary, the intrepid Kempner became an important figure, transferring movement members to hiding places. Abba Kovner (1918–1988), Arie Wilner (1917–1943), and other members hid in a convent. In the course of the mass murders, the Germans erected two ghettos in Vilna. The population of Ghetto No. 2 was destined for extermination. Kempner and Rozka Korczak, lacking the papers that would allow them to live in the ghetto, had to hide. A heated argument was held among the members of the Halutz movement as to whether to stay in the ghetto or attempt to save the members of the movement by finding a safer place. Abba Kovner, Haika Grosman, Kempner, Rozka Korczak, and others decided to remain in the ghetto, sustain the movement, and make arrangements for armed resistance. The turning point occurred on the night of December 31, 1941, when Abba Kovner read aloud his manifesto of the uprising: “Let us not go like sheep to the slaughter.” Possessing forged papers, Kempner was active for a while as a coordinator but requested permission to return to the ghetto: “I begged to be allowed to return to the ghetto … notwithstanding the risks, you are part of a group … you are among people who share a common fate.” At the same time, she insisted upon occasional participation in partisan missions.

Combined Armed Resistance

On January 21, 1942, the United Partisan Organization (Fareynigte Partizaner Organizatsye, FPO), was established. It was the only organization in the ghettos that included all the Zionist youth movements. According to Kempner, the organization was directed towards a single goal—armed resistance. “To do things other than those related to the FPO was unacceptable, to say the least. It was considered high treason. How could one be involved in a life of culture when the world was on the verge of destruction and Jews were going to die?” Kempner was the one who carried out the first act of sabotage against Germans. For a long time she patrolled and investigated the time-table of German military trains that reached Vilna—activity that involved mortal danger. Together with a partner, Itzke Matzkevich (d. 1943), she carried the explosives and hid them on the railroad track. Since the “Partizamka” (Partisan organization) did not yet exist in the forests in 1942, the Germans did not suspect that it might have been Jews who had blown up the train.

The major crisis in the underground took place in July 1943, when it became clear that the remaining Jews in the ghetto supported the surrender of the FPO commander, Yitzhak Wittenberg (1907–1943), to the Germans. Kempner painfully recalls the situation in which the youngsters, who assumed they had won the ghetto population over to rebellion, were in fact rejected by the Jews and regarded as the ones who jeopardized the ghetto’s existence. Kempner explained their decision to stay in the ghetto despite their exclusion: “We never thought in terms of rescue and living, but about a response adequate for Jews at that time.”

Underground Leadership

The final liquidation of the Vilna Ghetto and the deportation of the remaining Jews to Estonia occurred on September 23 and 24, 1943. Kempner was the one who moved regularly between the ghetto and the outside world through the sewage canals, leading underground groups and carrying ammunition to the meeting points outside the city, from which the groups departed to the forests. She led the last group of sixty fighters, including Abba Kovner, to the forests of Rodninkai. In the Jewish partisans’ camp, Kempner became the commander of the patrol group in charge of collecting information, maintaining contact with the underground in the city, transferring medications, leading units on combat missions, and performing acts of sabotage.

In addition, she guided groups of Jewish fighters to the forest until the Jewish camp numbered six hundred. The life of utmost poverty in the thick forest, in swampland, in an underground bunker was conducted with severe military rigor. The personal relationship between herself and Abba Kovner began at this time. The Jewish women, Kempner attests, were brave and determined in the execution of combat missions. She herself never took a thing from the farmers for her own benefit. “The comrades used to laugh at me and say that I was not a human being—you don’t need sleep or food and you don’t understand how a human being lives.” In July 1944, she was the first to reach liberated Vilna as the commander of a patrol unit, meeting Jewish Soviet soldiers for the first time, amidst great excitement and weeping. Kempner was awarded the highest badge of courage in the USSR.

Immigration to Palestine and Revenge

Immediately after their arrival in Vilna, Abba Kovner, Rozka Korzhak, and Kempner decided to find the surviving members of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir and promote immigration to Palestine. In January 1945, survivors from the youth movements, the partisans, and those returning from the USSR gathered in Lublin, where the temporary government of Poland had been established. Here they founded the Organization of Eastern European Survivors, headed by Abba Kovner, which aimed to promote the exodus of Jews from Eastern Europe. Kempner, who shared Kovner’s conviction that after the Holocaust there was no justification for the renewal of Jewish life in Europe, engaged in the smuggling of refugees across the border to Romania. Kovner also formed a secret “revenge” unit whose goal was to carry out revenge operations in Europe against persons who had committed murders or had been responsible for them. In July 1945, his unit reached Italy, where they were met with great enthusiasm by the Jewish Brigade, a British army unit, most of whose members were Palestinian Jews. Determined to devote themselves to revenge, the unit continued the war-time life of the underground. For them, World War II had apparently not come to an end. In their opinion, says Kempner, revenge should not be based upon the idea of terror, but be conceived as an essential public act, meant to execute historical justice upon the murderers.

Kovner left Italy in August 1945 and sailed for Palestine to obtain the material he needed for the planned revenge operations. On his return journey he was arrested by the British and imprisoned in Egypt. In February 1946 he was transferred to a prison in Jerusalem and released in April 1946. Meanwhile Kempner and the unit remained in Europe. The long months of plotting and involvement with the plan for revenge during 1945–1946, the problems involved in execution of the plans, the failures, and the opposition encountered from the Jewish community in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel. "Old Yishuv" refers to the Jewish community prior to 1882; "New Yishuv" to that following 1882.Yishuv leadership, left the unit with a feeling of bitterness and a sense of betrayal. Finally, the Haganah leaders in Europe persuaded the unit to leave Europe for Palestine.

When Kempner and the group arrived in Palestine in July 1946, Kovner and Rozka Korczak met them and convinced them to go to A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutz Ein ha-Horesh. There they were met with excitement, the kibbutz members vacating their rooms for the partisans in order to enable them to rest and recuperate.

The group engaged in heated arguments about proceeding with revenge operations. Kempner was among those who contended that it was time to end the war and start a new life. She worked in the fields and this hard work “open land, peace, fresh air and the fields” brought her back to life, despite her weakness and weight loss.

Kibbutz Life

At Ein ha-Horesh Kempner and Kovner decided to formalize their relationship and start a family. Michael, their first son, was born on May 27, 1948 in the midst of the War of Independence (November 30, 1947–July 20, 1949) while Kovner was serving on the southern front. When Michael was three, Kempner contracted tuberculosis. The manner in which she coped with the disease, the enforced separation from her young son and from her kibbutz home were marked by her usual determination. She decided not to be addicted to suffering and took up university studies by correspondence: history, English and French. The year she spent in hospital strengthened her awareness of the unique kibbutz togetherness. Despite the contagious nature of the disease, the kibbutz members were not afraid to visit her. Compelled to stay at home for an additional year, she could see Michael only from a distance—circumstances that caused her enormous pain. When she recovered, her doctors forbade her to bear children, and when she became pregnant and gave birth to Shlomit in 1956, the baby’s upbringing was accompanied by numerous prohibitions— “I was not allowed to kiss her, and could hardly touch her”—which increased her agony.

University Education

The determination to resume ordinary life was accompanied by a decision to engage in useful and interesting matters. Kempner was unable to adapt to the routine activities of the women kibbutz members, engaged in the sewing-room and kitchen. At her own initiative, she began helping children with their studies, eventually turning to the field of special education. At the age of forty-five, she decided to study clinical psychology as a full academic discipline. Bar Ilan University granted her permission to complete her studies for the first and second degrees in only three years. During her studies, inspired by Dr. George Stern, a lecturer in Psychology at Bar Ilan University, she developed a new form of therapy, “Non-verbal therapy by color,” which was implemented with great success in the Unit for Parent-Child Treatment at the Oranim Teachers’ College of the Kibbutz Movement. At the same time, she continued to help children at Ein ha-Horesh by tutoring, counseling and treatment, which was rare on the kibbutz. In time, she began instructing psychologists who wished to follow her therapeutic methods.

Marriage to Abba Kovner

During all these years, the creative and energetic Kempner was above all the wife of Abba Kovner, poet, leader, philosopher, and visionary. She accompanied his literary work and his rich and turbulent public life, while her kibbutz home served as a meeting place for artists, public figures and politicians. Here Kovner played the leading role, with Kempner in the shadows. Through Kovner she met the “great people,” she said. But she absorbed true eminence from Dr. Stern, and her work provided satisfaction and ongoing intellectual challenge. Kempner longed for the cultural milieu of the big city and found ways of fulfilling her need for theater and concerts. When Kovner fell ill with cancer in the summer of 1985, she accompanied him on the arduous road of medical treatments, standing by him when he had surgery in the United States and could no longer speak. Only after Kovner’s death in 1988 and Rozka Korczak’s passing in 1988 did her unique personality come to public light. Only then did people recognize her tremendous heroism in the days of the partisans and acknowledge her struggle to shape a meaningful, unique and worthwhile life of her own. Kempner described herself not as a survivor but only as strong. “I lived life fully, actively, without dragging grievances and offenses behind me.”

Vitka Kempner-Kovner passed away on February 15, 2012.

Kovner, Vitka. “Crossroads of Life.” Yalkut Moreshet 43–44 (August 1987): 171–176

Kovner, Vitka. “The Memory of the Shoah and its Lesson.” Yalkut Moreshet 56 (April 1994): 21

Kovner, Vitka. “In this she was special” an interview with Shmuel Huppert on July 13, 1988. In Rozka Korczak-Marla: The Personality, Philosophy and Life of a Fighter edited by Yehuda Tubin, Yosef Levi and Yosef Rab, 49–88. Tel Aviv: 1988.