Leah: Bible

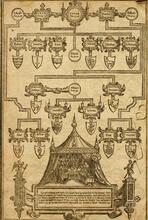

Leah is the sister of Rachel, and many of the stories about her center around her turbulent relationship with her sister, as they are both Jacob’s wives. Jacob clearly prefers Rachel, and God compensates Leah by making her fertile while Rachel remains barren. Both sisters ultimately bear Jacob many sons, and Jacob’s twelve sons eventually become the twelve tribes of Israel. But the sisters repeatedly compete with each other for Jacob’s affection, mostly by trying to bear him more children. Although Leah is given little attention outside of her complicated relationship with Rachel and Jacob, she and Rachel are remembered as the ancestresses “who built up the house of Israel” (Ruth 4:11).

Leah is the elder daughter of Laban and the wife of Jacob, father of twelve sons who will become the twelve tribes of Israel. Leah and her sister Rachel, whose names mean “cow” and “ewe,” give Jacob many sons; and their father gives him actual live-stock. Leah is described as having “soft (lovely) eyes” (Gen 29:17). Some translations (such as NJPS, RSV, NEB, and REB), perhaps influenced by Jacob’s preference for Rachel, render this as “dull-eyed” or “weak eyes,” but the more appropriate translation is “soft eyes” (as in NRSV and NAB)—what we might call “cow eyes.” She has six sons, who become six of the Israelite tribes (Gen 35:23; 46:5, 14).

Marriage to Jacob

Jacob sets out to Mesopotamia to marry from his parents’ collateral line. His father Isaac had married a first cousin, once removed; Jacob will marry his matrilineal first cousins and his paternal second cousins, once removed. In so doing, he too will marry into the family of Terah, the father of Abraham and Nahor, the grandfather of Rebekah, and the great-grandfather of Rachel and Leah. Jacob meets Rachel at a well (compare the stories of Zipporah and Rebekah) and falls in love. Penniless, he contracts to work seven years as his bride wealth.

After the wedding feast, in the dark of evening, Jacob goes in to consummate the marriage, but Leah has been substituted for her sister; in the morning, Jacob claims that “It was Leah!” (Gen 29:25). This is a multiple reversal: the trickster has been tricked, and the man who supplanted his elder brother marries the elder sister. Laban makes the message clear as he declares that the younger must not be married first. Jacob then arranges to receive Rachel at the end of the wedding week and thereafter to work another seven years to pay off her bride price.

Competition with Rachel

The two sisters are co-wives in competition for status in the household. Jacob clearly prefers Rachel (Gen 29:30). In compensation, God “opened [Leah’s] womb” (Gen 29:32), whereas Rachel proves to be barren. Perhaps the significance of Leah’s name comes into play here. Cows are a great symbol of fertility in Mesopotamia, partially because of the similarity between the words littu, “cow,” and alittu, “birthgiver.” Leah’s fertility quickly results in four sons.

Nevertheless, because of Jacob’s obvious preference for Rachel, Leah remains insecure and in the naming of her sons shows how she hopes to gain favor through bearing them. She names her first son Reuben (“see, a son”) her next one Simeon (“God heard that I am unloved”), the third one Levi (“now my husband will be with me”), and the fourth one Judah (“thanks! [NRSV, praise]”). At this point Rachel is jealous and has her maid Bilhah give birth to two sons; Leah, no longer fertile, responds by having her own maid Zilpah bear two sons (Gen 30:9–13; 35:26; 46:18).

The climax in the rivalry between the sisters/co-wives comes when Reuben finds mandrakes. Both sisters want them for their fertility-inducing powers and perhaps also for their aphrodisiac qualities. They strike a bargain: Leah will give Rachel the mandrakes in return for a night with Jacob. Leah crudely announces to Jacob that she has “hired” him with the mandrakes, and Jacob spends the night with her (Gen 30:14–17). When co-wives unite in purpose, husbands must comply. The new accord between the sisters helps Leah become pregnant (or the mandrakes work), for she gives birth to two more sons—Issachar (“God has given me my hire”) and Zebulon (“now my husband will honor me”)—and a daughter, Dinah (Gen 30:17–21).

Stories Beyond Rachel

The sisters are also in accord when Jacob asks them to come back with him to Canaan, but they are unhappy that their father gave them nothing of the bride wealth that Jacob provided in his fourteen years of service (Gen 31:3–15). Yet, like Rebekah, they affirm their choice to leave their parental home. They depart together, but despite all her children, Leah is still second best. When Jacob believes that danger threatens in his meeting with Esau, he arranges his family so that the maids and their children are placed first, then Leah and her children, and last and most protected, Rachel and Joseph (Gen 33:1–2; compare 32:22). Even after Rachel’s death, Jacob will continue to favor her son, Joseph.

Leah does not play the kind of role in determining the fate of her sons that Rebekah and Sarah did, perhaps because she never feels as secure as they did, and possibly because in a polygamous situation, co-wives have less influence except when they are united. The absence of a clear matriarchal hand shows itself in the uncontrolled friction between the children, but all the children of Jacob are to inherit the blessing. Nothing more is heard of Leah other than Jacob’s statement that he buried her in the Cave of Machpelah with Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah (Gen 49:31).

In Israelite tradition, the maid-mothers were forgotten, but Rachel and Leah were remembered. The prophet Hosea relates how Jacob went to Aram to search for a wife (Hos 12:13), and the wedding blessing for Ruth remembers Rachel and Leah as the ancestresses “who built up the house of Israel” (Ruth 4:11).

Brenner, Athalya. “Female Social Behaviour: Two Descriptive Patterns Within the ‘Birth of the Hero’ Paradigm.” Vetus Testamentum 36 (1986): 257–273.

Cohen, Norman J. “Two That Are One: Sibling Rivalry in Genesis.” Judaism 32 (1983): 331–342.

Jagendorf, Zvi. “‘In the Morning, Behold, It Was Leah’: Genesis and the Reversal of Sexual Knowledge.” Prooftexts 4 (1984): 187–192.

Meyers, Carol, General Editor. Women in Scripture. New York: 2000.

Ross-Burstall, Joan. “Leah and Rachel: A Tale of Two Sisters [Gen 29:31–30:24].” Word and World 14 (1994): 162–170.