Liz Lerman

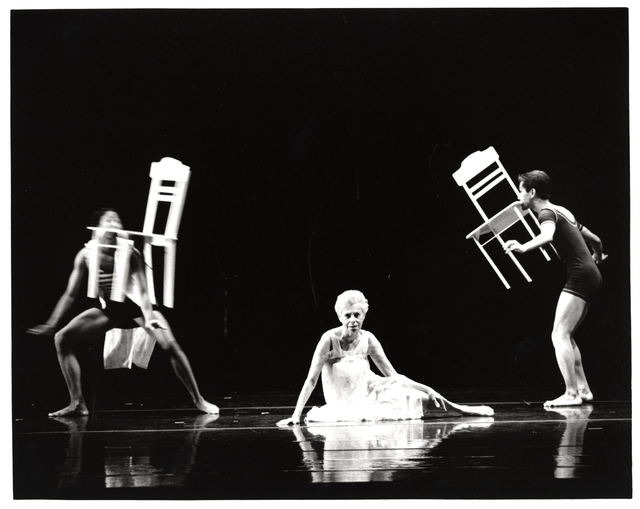

Liz Lerman uses dance to understand—and change—the world, or at least the way we think about it. Lerman brings deeply researched ideas about dance and community across fields as diverse as genetics, history, ethics of justice and reconciliation, and the science and religion of the origins of the universe. A choreographer, dancer, educator, writer, speaker, and all-around public intellectual, she has an expansive vision of dance in which everybody and every body can dance, from trained professionals to older adults, bodies of all types and abilities, ages, and levels of dance experience. She draws consciously on the Jewish value of tikkun olam—healing the world—in her work.

Liz Lerman’s visionary artmaking has seen her dances come to life from modest church halls and auditoriums to dancing in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty, from the loading dock of the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., to performing in the Large Hadron Collider at CERN in Switzerland.

Raised in the Reform movement and influenced by her father’s political activism, the dancemaker delves deeply into subjects not typically seen as suitable for dances. Lerman’s choreographic process frequently relies on intense collaboration, deep questioning and extensive research, including interviewing experts such as historians, clergy, scientists, mathematicians, professors, and legal scholars on the topic she is researching.

Personal Background

Born in Los Angeles on Christmas day, December 25, 1947, Elizabeth Ann Lerman was the second child and only daughter to Anne (Levey) and Philip Lerman. A San Franciscan, Anne studied engineering the University of California at Berkeley and took graduate classes at Stanford University then worked as a draftsperson during World War II. Phil Lerman, born and raised in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, became active in Jewish youth groups, such as the progressive Zionist Hashomer Hatzair, and briefly belonged to the Communist party. Though the family business was Lerman’s Tires, Phil became a political organizer, working for the Anti-Defamation League, among other organizations. Phil and Anne moved the family a few times to Milwaukee, Washington, D.C., and back to Milwaukee during their daughter’s childhood.

Becoming a Dancer

In Washington, Lerman’s mother enrolled Liz in modern dance classes, taught by former Martha Graham dancer Ethel Butler. Back in Milwaukee, where the family joined the Reform Temple Emanu-El, Lerman studied dance with Florence West, later writing of West’s classes: “Anything was possible, except playing with scarves. I think Florence was afraid we might suffer the same fate as Isadora” Duncan, who was strangled by a carelessly tossed scarf. At 14, while a camper at Interlochen Arts Camp, Lerman was among a group that danced for President Kennedy at the White House.

As a teenager, Lerman became increasingly aware of the inequities in Milwaukee through her father’s community activism on behalf of the city’s Black community, which faced high unemployment, unequal housing and segregated schools. Lerman graduated high school early, worked a clerical job, and began college in 1965 at Bennington, then did a brief stint at Brandeis before moving to Washington, D.C., in 1967, where she completed her degree in dance at the University of Maryland. There her choreography professor Meriam Rosen said, “I was very impressed with her from the start.” For nine months in 1973–1974, Lerman lived, studied dance, and worked in New York, the epicenter of modern and post-modern dance. There she saw the effects of the Judson Dance Theater movement, which stripped dance of meaning, narrative, technique, and hierarchy, ideas about which she had already been thinking. She also earned money as a go-go dancer, which became the subject of her 1974 solo “New York City Winter.”

In 1975, one of Lerman’s earliest pieces, Woman of the Clear Vision, remembered her mother Anne Lerman, who had died that year. The work honored her mother’s life, and the choreographer saw it as shepherding her into the realm of death where ancestors—aunts, uncles, cousins—would meet her. Liz Lerman worked with residents of a senior adult apartment in Washington, D.C., incorporating them into the choreography. A few of these elder performers stayed on to become Lerman’s popular senior dance company Dancers of the Third Age (1975–1993), who performed with young professional dancers who performed in schools, senior centers, and theatrical venues in Washington and throughout the East Coast.

Founding Company

In 1976, Lerman founded Dance Exchange, a studio, school, and company now based just outside the Washington, D.C., line in Takoma Park, Maryland. She served as artistic director and primary choreographer until stepping down in 2011 and leaving Dance Exchange in the hands of artistic director Cassie Meador. During her 35-year tenure at the helm of her multigenerational company, she choreographed more than 80 dances. Since departing the company, Lerman has served as professor at the cross-disciplinary Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts at Arizona State University, where she teaches both dance students and other arts majors her boundary-melding philosophy of artmaking, which blurs hierarchical ideas for a more democratic and inclusive approach.

Jewish-Themed Choreography

For her explicitly Jewish works, Lerman has wrestled with questions of belief in God and what it means to be an American Jew. These works included Miss Galaxy and her Three Raps With God (1977), Russia: Footnotes to History (1986, about her grandfather’s Russian Jewish roots), The Good Jew? (1991), Shehechianu: Faith and Science on the Midway (1996), and The Hallelujah Project (1998–2002). And yet, almost all Lerman’s highly researched “narrative non-fiction works,” as she has defined them, draw on her Reform Jewish values steeped in social justice and liberal political leanings – thus a piece dealing with war or grief or a one-time navy shipyard can contain Jewish DNA. Those works with a subtext of socio-political justice include her 1982 and 1983 Docudances,” respectively subtitled “Reaganomics (No One Knows What the Numbers Mean)” and “Nine Short Dances About the Defense Budget and Other Military Matters.” In 2005, Lerman examined genocide, guilt, and reconciliation with Small Dances About Big Ideas, commissioned by Harvard Law School on the 60th anniversary of the Nuremburg Trials. This work dealt with the possibility of legal justice utilizing journalistic accounts from Rwanda’s genocide and the nation’s truth and reconciliation program. Lerman delved into physics and astronomy with two large-scale works: Ferocious Beauty: Genome (2006) and The Matter of Origins (2009). In Genome, the choreographer worked with scientists who mapped the human genome to tell the story of human genetics, while in Origins she worked with physicists and astronomers and a rabbi to examine the origins of life itself.

Artistic Process

Lerman favored the non-hierarchical ideals and democratic bent of Judson, but she preferred her dances to convey stories and present meaningful—often personal—narratives; inspired by a Merce Cunningham work that used a spoken dialogue, she also began experimenting with spoken-word dances. She came to believe that dance is not about the steps, but rather about how engaged and committed performers are to conveying experiences or ideas through movement.

Lerman’s investigative process draws on personal experiences—her own, those of her dancers, and those collected in workshops where participants, often with no formal dance training, are encouraged to share stories and illustrate them with their own movements. She also reads broadly and deeply on her topic-driven works.

Lerman sees her role as a disseminator of ideas, a public intellectual of dance and performance. Over the years she has collected the numerous exercises and practices she uses in her workshops and choreographic process. She wrote: “I was driven to discover questions and structures that would help people find physical answers and stories inside themselves.” These tools are available online in “The Atlas of Creative Tools: A Creative Toolbox” for use by students and professionals.

Some prominent dance critics have not appreciated Lerman’s populist, often wry or humorous approach set forth in her dances. This led her to develop her now-renowned Critical Response Process (CRP), a systematic approach to giving and receiving feedback to creative work that centers the artist and the process, rather than the opinion of the viewer. Since its inception in 1990, CRP has garnered fans across the country and around the world and is taught in university performance and art departments and writing classes; clergy and school systems have used it, as have chefs and social science researchers. The four-step process focuses on guided concrete statements about the work and specific, neutral questions to the maker. Opinion is only solicited in the final step, if the creator wants to hear it. In 2003 Lerman, with co-author John Borstel, wrote the handbook Liz Lerman’s Critical Response Process: A Method for Getting Useful Feedback on Anything You Make, From Dance to Dessert.

Accolades

: Lerman has received the American Jewish Congress Golda Award, the Dance/USA Honor Award, American Dance Guild Lifetime Achievement Award, a Guggenheim Award, the American Dance Festival Teaching Award, and the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Award, among many others. In 2002, she received a MacArthur “genius” grant, which cited how Lerman “builds community, encourages personal insight, and choreographed dances that have been called visionary, profound, and revelatory.” She has been an artist in residence and visiting professor at Harvard University, an advisor on Synagogue 2000 (a decade-long cross-denominational project aimed at transforming the American synagogue), and a visiting scholar at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, where she taught rabbinical and cantorial students a course called “Moving the Synagogue.”

In 2011, Wesleyan University Press published Lerman’s collection of essays, Hiking the Horizontal: Field Notes from a Choreographer. Her Critique Is Creative, a collection of essays from Critical Response practitioners, will be published by Wesleyan University Press. In 2020, Lerman joined the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts as an inaugural senior fellow. This multi-year program centers artists as leaders offering a creative home for creatives, curators, changemakers, and thinkers to develop new ideas and build community. As of 2021, she is choreographing “Wicked Bodies,” which grew from images and ideas gleaned from an exhibit on witches. Lerman describes the full-evening work as “a history of sly, grotesque, sensual, wildly creative women that every culture carries in cliches, stereotypes, and fictions because they are actually very real and very present” (https://lizlerman.com/wicked-bodies/). The work is expected to premiere in 2022.

Lerman is married to performer and storyteller Jon Spelman. Their daughter, Anna Clare Spelman, is a photographer and documentary filmmaker.

Every Lerman project is built upon the dancemaker’s ethos “dance for everybody,” which she has expressed in four elemental questions that drive her work and served as Dance Exchange’s mission statement for many years: “Who gets to dance? Where is the dance happening? What is it about? Why does it matter?”

Website: https://lizlerman.com/

Kriegsman, Alan M. “Democrat of Dance.” The Washington Post, April 26, 1987, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/style/1987/04/26/liz-lerman-democrat-of-dance/32be4688-6b60-4537-a4a7-8d6555ab69e8/

Lerman, Liz. Hiking the Horizontal: Field Notes From a Choreographer. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2011

Lerman, Liz, and John Borstel. “The Dance Exchange Toolbox.” http://www.d-lab.org/toolbox/about

Silver, Laura. “Moving Prayers.” The Jerusalem Report, Jan. 8, 2007, p. 36-39

Traiger, Lisa. “Making Dance That Matters: Dancer, Choreographer, Community Organizer, Public Intellectual Liz Lerman.” MFA thesis, Theater, Dance and Performance Studies, University of Maryland, 2004, https://drum.lib.umd.edu/handle/1903/1399?show=full

Traiger, Lisa. “Separating the Dancer from the Dance.” The Forward, June 22, 2002, https://forward.com/culture/138987/separating-the-dancer-from-the-dance-exchange/