Maskilot, Nineteenth Century

Despite assumptions that the Haskalah was an exclusively male movement, some Jewish women read canonical Hebrew texts and Haskalah Hebrew literature, wrote in Hebrew, and wished to take part in the cultural and social revolution the Haskalah preached. Because maskilot rarely published their work and only a small number of women’s letters remain in the archives, only a partial picture of their participation exists. Most maskilot expressed themselves in non-canonical way, including various kinds of correspondence, translations, and social essays. Only a few dared write in the canonical styles of poetry and narrative. Their writings have led to a new understanding of the history of modern Hebrew women’s literature, which emerged in the 1860s rather than the 1920s hitherto understood.

Introduction

The Hebrew term female/sing.: Member of the Haskalah movement.maskilot refers not only to the ideology of Jewish women proponents of the Jewish Enlightenment; European movement during the 1770sHaskalah (Enlightenment) movement of nineteenth century, who wished to take part in the cultural and social revolution that it preached, but also to their language: these were women who wrote in Hebrew.

The historiography of the Haskalah movement assumed that, as a result of women’s ignorance of Hebrew and its canonical texts, the Hebrew Haskalah was a “male movement.” Indeed, as a direct consequence of Jewish women’s exclusion from Hebrew (the "Holy Language") and its culture (since women were forbidden to learn Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah), women’s education, when at all given, was channeled into two “suitable” or “permitted” linguistic streams: one consisted of European languages such as German, English, and Russian; the other was the Jewish vernacular, Yiddish. Since women were thus excluded from the Jewish canon in general and Haskalah literature in Hebrew in particular, it is surprising to find women proponents of the Haskalah (maskilot) who read Hebrew literature, wrote in Hebrew, and regarded themselves as part of the Haskalah movement.

Becoming a Maskilah

The discovery of Hebrew writings by some 30 women in manuscript archives and Hebrew-language literary periodicals of the Haskalah period (collected in an anthology by Cohen and Feiner, Voice of a Hebrew Maiden, 2006) dispels the conventional belief that women were silent during that time. Women not only studied canonical Hebrew texts and read Haskalah Hebrew literature, but in their writings they also put to active use their knowledge of the language, their ability to express themselves, and their creative talent. The picture of this phenomenon is still only partial and will perhaps never be complete: Jewish maskilot seldom published their work, and only a small number of women’s letters remain in the archives. One might therefore presume that many more women read and wrote Hebrew than those whose writings have been found. Moreover, while the women who wrote letters and even those who published essays and literary works signed their own names to them, many are virtually untraceable. Although in some cases we are aware of biographical details, in others we know only the date of composition or the writer’s place of residence.

Women did not enter significantly into the circle of the Hebrew enlightenment during its early phase, when its main centers were located in Germany and Galicia. They did so only in the second half of the nineteenth century, when Russia and Lithuania became the principal centers of Haskalah activity. From what we know of the biographical details of the maskilot, we can deduce why this phenomenon grew stronger at that time and in those locations.

The prime, essential prerequisite for a woman to become a maskilah was a high-level of proficiency in Hebrew and familiarity with Hebrew canonical texts. Girls received no such education in any accepted traditional setting in the mid-nineteenth century, not even in the Haskalah-run schools, which limited the Hebrew and Bible taught to girls. Jewish women of the nineteenth century had no keys to the locked gate of Hebrew unless their fathers deliberately provided them to her—and that occurred only when the father concerned was himself a maskil and favored girls’ education. Hence, the Hebrew maskilah belonged to the second generation of the movement.

Another environmental characteristic that encouraged the forming of the “Hebrew maskilah” typically reflected mid-nineteenth-century economic and social changes. The entry of women into the creative literary world increased with the rise of the middle class and the subsequent easing of women’s way of life and improvement in their education. Jewish women wrote, both in modern European languages and in Hebrew, when—as was increasingly the case in that period—their socio-economic conditions allowed and during the free time that resulted from the rise in their age of marriage. To this one must also add, in some cases, the considerable influence of Russian radical ideology, which preached the creation of a “new woman” by improving her education to equal that of a man’s. In the 1860s the maskilim first encountered this ideology, which bestowed legitimacy on women attempting to integrate into the social and literary movement of the Haskalah and encouraged those efforts.

Literary Genres

Most Hebrew maskilot suffered from “anxiety of authorship” (as defined by theoreticians Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar), which characterized women’s work in the first stages of their entry into the patriarchal cultural world. They therefore expressed themselves in non-canonical ways that reduced their anxiety: various kinds of correspondence, translations, and social essays. Only a few of them dared to write in the canonical styles of poetry and narrative.

LETTERS

Letters written by maskilot in Hebrew were the bridge that facilitated their entry into fields of Hebrew enlightenment writing. Ever since the seventeenth century, private letters had been accepted in European culture as a suitable “feminine” way for self-expression for women. This mode was considered to be the least harmful to the writer’s “legitimate” feminine image and culturally the most comfortable for her. At the same time, the Hebrew letter was a common and widespread literary form among Jewish maskilim who, because they were few and scattered, needed this tool to create a cultural community. The Hebrew maskilah thus used the maskilic Hebrew letter as a way to be included in the maskilim’s “network of connections,” while writing in an appropriately feminine manner.

While only one complete archive of a woman’s correspondence is extant—that of Miriam Markel-Mosessohn (1839-1920)—other letters were preserved in men’s archives. These include the letters women admirers wrote to Judah Leib Gordon (1831–1892) [including letters written by Rivka Rottner (b. 1872), Shayna Wolf, Sara Shayne Rahavsky, Sarah Shapira, and Nehama Feinstein (1869–1934)]; letters from two women (Shulamit Pilpel and Betty Gold) to Rabbi Dr. Juda Loeb Landau (1866–1942), which are preserved in his archives; one from Sarah Shapira (1866-1932?] in the archives of Perez Smolenskin (1840–1885); and a letter from Esther Goldman found in the archive of Shneur Sachs (1816–1892). Other private correspondence (together with letters to the editors of periodicals) was published in periodicals or collections of correspondence, almost certainly with the writer’s permission. Some of the printed letters were indeed private, addressed mostly to the writer’s father (the letter of Leah Bermanson to her father, Ha-Shahar 1874; Bertha Rabinovitch to her father, Ha-Shahar 1874; Sarah Cohen Nevinsky to her father, Ha-Shahar 1880). Other letters were written to an author or newspaper editor who was not personally acquainted with the writer [Rachel Morpurgo (1790-1871) to Mendel Stern, Kokhvei Yizhak, 1849–1850; Shifra Alchin to the editor of Ha-Meliz, 1863]. Most of the letters combine the writer’s personal, family, and experiential world with discussions of general national, public and cultural problems.

The letters reveal a model of the maskilah cultural identity. Most are written in rich, precise language and contain numerous canonical references. They thus indicate, first and foremost, that the woman who wrote letters in Hebrew was very well acquainted with the language and its canonical textual sources. The writers acquired their knowledge by conscious and deliberate effort and many of them describe both their determination to learn the language and their love for it. Not surprisingly, the Hebrew maskilot writers were also readers of Hebrew books, not only canonical texts but also contemporary Hebrew literature. Many letters indeed deal with the influence of Hebrew literature on the writer’s life and consciousness and her reactions to a specific work. Only a few maskilot address the Haskalah ideology of social reform in their letters. The only reform that seems to interest some of them and finds expression in their letters (and also in several articles, as we will show below) is the change required in the education of Jewish girls and the aspiration for cultural equality for women.

SOCIAL ESSAYS

The publication of feminine social essays in Haskalah-era Hebrew periodicals breached another barrier to the Jewish maskilah’s integration into the maskilic creative endeavor. Unlike a letter directed to a specific recipient, the essay, which is addressed to the entire public of maskilim, is a part of the accepted maskilic style. [The essay was the ideational focus of the Haskalah from the time of the essay “Divrei Shalom ve-Emet” (1782), by Naphtali Herz Wessely (1725–1805)]. The essays written by maskilot sometimes focus on female protest against the discrimination leveled against them by traditional Jewish society and the need to improve girls' education.

Several writers used the epistolary form in their essays. Thus, an 1876 essay by Olga Belkind (1852-1943), in which she asks the public to support young women studying midwifery, was written as an open letter to the Warshawsky family, who at the time supported her own midwifery studies. Miriam Leichtman also wrote her essay, “On the Question of Women’s Education” (1896), in the form of a “letter to the publisher.” Only a few essays focused on conventional maskilic “male” ideology, as did Sarah Feiga Meinkin Foner (1855-1937) in “The Spring” (1876) and Marka Altschuler in “Thoughts on the Ninth of Av, My Birthday” (1880). Most essays by maskilot consisted of penetrating feminist critiques of the education and status of Jewish women both in traditional Jewish society and among the maskilim. In addition to Olga Belkind’s aforementioned letter, four other essays on this subject were published: “The Woman Question” (1879) by Taube Segal, “More about the Question of Girls” (1889) by Nehama Feinstein, “I Am An Example for Many” (1895) by Devorah Weissman-Hayut, and “On the Question of Women’s Education” (1896) by Miriam Leichtman.

The writing of Hebrew essays posed a special linguistic challenge for the female writer, when wishing to express modern feminist positions in canonical “male” language of the sources, to which such opinions were alien. To this end, the maskilot applied the main principle of maskilic tradition: a fresh reading of the traditional source that allowed it to be used for personal expression, in their case feminine and/or feminist interpretation.

TRANSLATION

The widespread enterprise of translation from European languages into Hebrew characterized the Haskalah from its beginnings and was based on an awareness of the importance of integrating European culture into the Hebrew Haskalah. The outstanding example of a maskilah who chose translation as her initial intellectual creative field of endeavor in the Haskalah’s public sphere was Miriam Markel-Mosessohn. Her best-known translation is of the history book by Isaac Asher Francolm (Eugen Rispart), Die Juden und die Kreuzfahrer (1841), under the Hebrew title Ha-Yehudim be-Anglia: o Ha-Yehudim Ve-nosei ha-Tzlav (The Jews in England, or The Jews and the Crusaders, 1869).

In the fields of poetry and fiction, the Maskilot's literary activity was rather limited, probably because these were considered the dominant fulcrum of Hebrew literature and therefore male preserves. We know of three poets (only one of whom, Rachel Morpurgo, published more than a few poems) and one significant author, Sarah Feiga Meinkin Foner.

The poems that the three poets of this period wrote indicate the ways in which women dealt with male literary tradition. Two poems by Hanna Blume Sulz of Vilna (“The Play,” 1882, and “The Valley of Revelation,” 1883) display her excellent knowledge of Hebrew and her familiarity with contemporary Hebrew poetry and poetics. However, the female writer surrendered to the masculine tastes of the time, thus losing her feminine authenticity and undermining the poems’ success. Two poems by Sara Shapira (the poetic allegory “Remember the One Caught by a Horn,” 1886, and the nationalist poem “Zion,” 1888) were also written in contemporary format and identified with normative maskilic ideology, with no explicit expression of the female speaker. Yet unlike the stifling of authentic expression of the female voice in the poetry of Blume Sultz, Shapira’s poems contain some form of that expression. Female expression is felt especially in the poem “Remember the One Caught by a Horn,” which uses a lively portrait of a suffering kitchen-maid in order to attack the way the rich treat the poor.

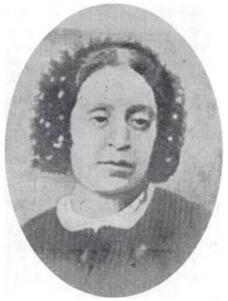

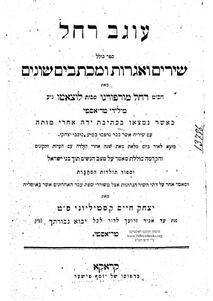

A first poetic expression in Hebrew of women’s world and their problems may be found in the work of the first Hebrew woman poet of the time, the Jewish-Italian poet Rachel Morpurgo, from Trieste, whose poems and letters were collected in book form only after her death (Rachel’s Organ, 1890). Morpurgo’s 50 poems (many published during her lifetime in the journal Kokhvei Yizhak, or The Stars of Isaac) include not only poems written for family, community, and national occasions (for example, "A Poem of Praise," in honor of Sir Moses Montefiore, and "About the Refugees from the Cholera Plague"), but also a major body of poems of personal contemplation (including “See, This Is New,” “Lament of My Soul,” “Why, Lord, So Many Cries,” “O Troubled Valley,” and “Until I Am Old”). All of Morpurgo’s poems express not only a complex and deep personality but also scholarly knowledge of canonical Hebrew sources and an excellent ability to use the poetic norms of her time. The power of many of her poems derives from their having been written on two levels, in a form termed “palimpsest” by the feminist literary critics Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar. The external and obvious layer displays the accepted cultural conventions of contemporary masculine poetry and social norms, which often contrast with the second subtle layer of the work, one that can be deciphered by following the sources of the canonical references. Once those sources are joined together, the poem's subversive meaning is uncovered. We thus hear the voice of a woman describing her suffering and protesting against her inferior status in Jewish society and culture, and also that of an Orthodox and nationalistic person who protests against the assimilatory norms of mid-19th-century Trieste. Though Morpurgo was rather well known and appreciated in her time, her poetry was later denigrated and forgotten. Since the late 1990s it has earned renewed regard and appreciation.

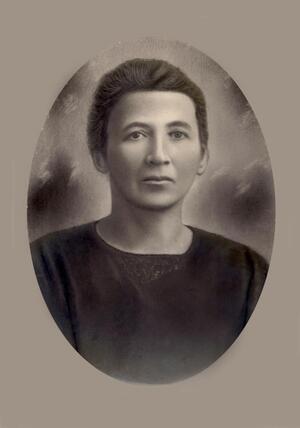

Only one woman dared to compose fiction, a field at the center of male maskilic writing in the last third of the Haskalah period. This was Sarah Feiga Meinkin Foner, who published four Hebrew books, two of which were works of fiction: The Love of the Righteous or the Persecuted Families (the first volume in 1881; the second was not published for financial reasons) and The Treachery of Traitors (1891). The third was a children’s didactic story, Children’s Way, or A Story from Jerusalem (1886), and the fourth consisted of her memoirs (Memories of My Childhood, or A Memoir of Dvinsk, 1903). Her major work, the novel The Love of the Righteous or the Persecuted Families, seems a typical maskilic novel, faithful to the conventions of the genre: a romantic plot in which the admirable maskilim protagonists clash with a conservative, conventional society, represented by contemptible and hypocritical characters. When judged according to these conventions (as the famous critic David Frishman did), the work is not very impressive. However, when read in the context of a revolution by the first female Hebrew author, its uniqueness and achievement become apparent. For the first time in Haskalah fiction, a female maskilah protagonist–the heroine, Finalia—assumes an active role both in her life and in the plot. We also hear, for the first time in Hebrew novels, the voice of a female author. She empathizes with the heroine, when describing her relationships with other women; she describes in detail the women's world and expresses criticism of the Hasidic education of girls. However, Foner's later historical novel (The Treachery of Traitors) and the children’s story (Children’s Way) mark a retreat from the expression of the female voice, perhaps as a result of the cold reception accorded to her “female” novel. Both works are more pleasant to read, and it seems that the writer’s language had improved in the course of the decade that had elapsed since she wrote her first work, but those stories lack the emotional and feminine authenticity present in her first book.

Feminist Protest Writing

Hiding the protest

Most Hebrew maskilot writers surrendered to the conventions regarding “the feminine” (according to Elaine Showalter’s definition of the levels of development of women’s writing), restricting themselves to private writing (letters) or, in a few cases, bi-layered writing, with feminist protest expressed only on the implied level of the text. Only at the end of the period did feminist protest appear openly.

The voice of feminist protest is heard quite frequently in women’s private correspondence. The mere expression of protest against women’s status shows the writer’s awareness of it, but also her need to conceal and limit protest to the private, “feminine” sphere. Thus, in a letter published in Ha-Maggid in 1870, Bertha Kreidman describes with painful cynicism the normative feminine ideal of a brainless pretty woman, which gives rise to negative social attitudes towards a girl (like her) who loves learning and is capable of writing in Hebrew. In an early letter (to Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Landsberg, July 1863), Miriam Markel-Mosessohn protests against the disregard for women’s education; later, in a letter to Judah Leib Gordon (undated, possibly 1868), she describes the gap between her feminist opinions and her realization that it would be better not to air those opinions in public. Furthermore, in a personal (undated) letter to her brothers Joseph and Simon, Markel-Mosessohn conceals a short story with a clearly feminist message. The letter seems to be personal, describing an event in the city of Suwalk. Yet the cloak of personal “feminine” gossip conceals the first feminist maskilic story, which even has a title: “The Suwalki Woman’s Wisdom Is Like That of the Woman of Tekoa.” This is a well-written story with a double agenda, both social-maskilic and gender equality: a confrontation between the religious establishment, represented by a man, the rabbi, and the simple people, represented by a woman. The conflict ends with the woman’s victory.

A feminist protest is also hidden beneath layers of “proper” humble female expression in some of Rachel Morpurgo's poems. Most of this protest is directed against the limiting, humiliating traditional perceptions of women’s spirituality in Jewish society. Her protest is never expressed bluntly and is always half covered by an external layer of seemingly conservative female acceptance of the religious and social Jewish norms.

Overtly feminist expression

Like the dominant trend at the outset of Russian feminism in the 1860s, and probably under its influence, Jewish feminism, from the first, concentrated on demanding that women be able to learn a profession. Olga Belkind, a graduate of the midwifery institute in St. Petersburg, described in her letter (Ha-Shahar, 1876) the revolution taking place in Jewish girls’ consciousness regarding their need to train for a profession (midwifery in this instance) and the gap between this awareness and the Jewish community’s lack of preparation for a response. Taube Segal of Vilna, in her essay “The Woman Question” (1879), also saw women’s professional training as the opening to women’s equality. Segal took to task Jewish men from all sectors of society—the maskilim, the Orthodox, and the “average ones”—for their discrimination against women. She claimed that despite the fact that equality was supposed to be at the center of the Haskalah revolution, it did not include women. Segal uses sharp irony when describing Jewish male attitudes to women, including maskilim whose amazement when confronted with a learned woman reveals their chauvinism; they don't really regard maskilot as creatures equal to themselves in intellectual ability.

The discovery of women’s writing in Hebrew during the Haskalah period and its inclusion in the historiography of modern Hebrew literature change our understanding of the Haskalah movement and its literature, and also of the historiography of Hebrew literature in general. The Haskalah was indeed a “man’s movement” in its goals and character, like most social and cultural movements of the period. But the existence of Hebrew writings by maskilot provides evidence of women’s attempt to be included in the movement and to include within it the issues that were important to them. Women’s writing represents a different way of perceiving women, society, and culture and is characterized by its own solutions to the representation of women, the feminine, and feminism in literature. In its very differentness, women’s writing also emphasizes the gender-masculine elements of canonical Haskalah literature.

The writings of Hebrew maskilot have also led to a new understanding of the historiography of modern Hebrew women's literature. Modern Hebrew women's writing emerged, we now know, several decades prior to the time hitherto accepted—that is, in the 1860s rather than in the 1920s.

Cohen, Tova. “Portrait of the Maskilah as a Young Woman.” Nashim 15 (1998):. 9-29.

Cohen, Tova. “The Maskilot; Feminine or Feminist Writing.” Polin 18 (2005): 57-86.

Cohen, Tova. A Silenced Harp: The Life and Works of the Italian-Hebrew Poetess Rachel Morpurgo. Jerusalem: Carmel, 2016. [Hebrew]

Cohen, Tova and Shmuel Feiner. Voice of a Hebrew Maiden: Women's Writings of the 19th Century Haskalah Movment. Tel Aviv: Hakibiz Hameuchad, 2006. [Hebrew]

Fram Cohen, Michal. “The First ‘New Woman’ in Modern Hebrew Literature: Pinellia Adelberg in Love of the Righteous, or, the Persecuted Families by Sarah Feiga Meinkin." In Emancipation Women's Writing at the Fin de Siècle, edited by Elena Shabliy, 94-119. London and New York: Routledge 19th Century Series, 2019.

Foner-Meinkin, Sarah Feiga. A Righteous Love, or The Pursued Family (Hebrew). Vilna: 1881. [Hebrew]

Foner-Meinkin, Sarah Feiga. A Story from the Days of Shimon the High Priest. Warsaw: 1891. [Hebrew]

Foner-Meinkin, Sarah Feiga. Children’s Way, or A Story from Jerusalem. Vienna: 1886. [Hebrew]

Foner-Meinkin, Sarah Feiga. The Days of My Youth, or A Memoir of Dvinsk. Warsaw: 1903.

Gilbert, Sandra and Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979.

Morpurgo, Rachel. Ugav Rahel. Cracow: 1890. [Hebrew]

Parush, Iris. Reading Women: The Benefit of Marginality in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society. Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 2001. [Hebrew]

Rosenthal, Morris, ed. and trans. A Woman’s Voice: Sarah Foner, Hebrew Author of the Haskalah. Wilbraham, Mass: Dailey International Publishers, 2001.

Showalter, Elaine. “Towards a Feminist Poetics.” In Women Writing and Writing About Women, edited by Mary Jacobus. London: Croom Helm, 1979.

Werses, Shmuel, ed. The Poet’s Friend: The Letters of Miriam Markel-Mosessohn to Judah Leib Gordon. Jerusalem: Mosad Bialik, 2004. [Hebrew]