Mexico

Jewish immigration and life in Mexico can be divided into three periods: the colonial, beginning in 1492, the Porfiriato, from 1876 to 1910, and the modern, from 1917 onwards. Three main groups constitute the modern Mexican Jewish community: Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazim; Sephardim; and Jews from the Levant, mostly of Syrian descent. Each group has developed its own religious, educational, cultural, and social organizations. Women’s main organizational framework in the building of Mexican Jewish institutions was that of cultural activities, artistic and social endeavors, and philanthropic aid societies. Jewish women today are part of a changing society where new generations, profiles, and activities are redefining their spaces as well as the role and status of the organized Jewish community as a whole.

In Mexico the organizational and cultural models created throughout the period of Jewish immigration determined the status of women both within the Jewish community and in Mexican society at large.

Overview of the Mexican Jewish Community

Mexico’s search for a national identity and culture as a basis for national unity engendered an emphasis on ethnic and cultural homogeneity. The ideal of Mestizaje (crossbreeding of ethnic groups), as developed in the later part of the nineteenth century and at the beginning of the twentieth, was a means to achieve such national unity and was centered on two main groups: the Spanish and the indigenous population. This ideal also helped to identify a new political elite. The fear of diversity as a threat to national unity confronted ethnic minorities with the alternative of either assimilation or existence as an enclave that was not accepted as a legitimate member of the national entity.

Two realities interacted during the process of building Jewish life in Mexico. While the small size of the community and its lack of material resources led to centralization, the diversity of traditions, customs, and cultural practices strengthened internal differentiation and diversity. The latter may be seen as a specific trait of the Mexican Jewish community and as a central principle of self-definition. Organizational life pivoted around ethnic-communal origins that defined the main groups within the Jewish community. Each group experienced its own interaction with modernity and thus also the place of Jewish women within it.

Although today’s Mexican Jewish community has its origins in the waves of immigration in the last years of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth, its history can be traced to the expulsion of the Jews of Spain and the discovery of the New World in 1492. The new colony Nueva España (New Spain) became a haven for the Spanish and Portuguese Crypto-Jews; although illegitimate within the margins imposed by the Inquisition, they distinguished themselves in the creation of the new society. Due to the ongoing activities of the Inquisition in Nueva España, the Jews remained confined to their secret observance and were systematically persecuted until 1820. Most notable was the Carvajal family, executed at the end of the sixteenth century, among whom was Mariana Carvajal, whose Auto de Fe was immortalized in Mexican art and literature.

History of the Mexican Jewish Community: El Porfiriato

The first signs of a developing Jewish community may be found during the long presidency of Porfirio Díaz (1876–1910), known as the Porfiriato. Jews arrived in Mexico in response to the call for foreign investment to participate in the modernization of the country. The predominant Jewish immigrants were emancipated and assimilated Jews from France and Germany who did not fully identify with Judaism. Many of them married Mexican Catholic women and became undifferentiated members of the new society. These Jews were part of the economic and governmental elite and the women were not employed. A notable exception is Estela Wolfowitz, whose family came from France and who, in 1912, was hired as marketing manager of the upscale department store El Palacio de Hierro in Mexico City.

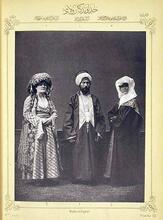

In the last years of the Profiriato, Mexico witnessed a new, though reduced, Jewish presence with few economic resources. New immigrants came from the Ottoman Empire and Eastern Europe. Most of them were shoemakers, furriers, traveling salesmen ,or tailors. They settled in provincial towns such as Puebla, Veracruz, and Chiapas, before moving to Mexico City. Economic need dictated the participation of women in their husbands’ activities. In the family business and at home the Jewish women affirmed their importance as breadwinners.

Turkish Jews, who had been holding religious services since 1901, founded the first Lit. "study of Torah," but also the name for organizations that established religious schools, and later the specific school systems themselves, including the network of afternoon Hebrew schools in early 20th c. U.S.Talmud Torah in 1905/6, conceived as an educational institution exclusively for boys. It was not until 1939 that girls were admitted. Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazi Jews held services in a Masonic temple as early as 1904. The first formal Jewish organization in Mexico, the Monte Sinai Community, was founded on July 14, 1912.

History of the Mexican Jewish Community: Mexican Revolution to Present

During the Mexican Revolution (1910–1917) a time of profound social and economic upheaval, most foreigners, including Jews, left the country. It was immediately after this period of turmoil that Jews arrived in Mexico in substantial numbers. Between 1917 and 1920 thousands of Jews from Russia, Poland, Lithuania, the Balkans, and the Near East reached the country. The wave of immigration that would comprise the bulk of the Jewish community began in 1921, as a result of the limits to immigration set in the United States by the quota system. Among those who acclaimed Mexico as a haven for Jewish immigration, “Another Promised Land,” was Anita Brenner (1905–1974), journalist, historian, anthropologist, art critic, and writer who moved in the most prestigious intellectual circles in Mexico and abroad. She served as the correspondent of the North American Jewish Telegraphic Agency and portrayed the Mexican cultural milieu to European and American Jewish organizations that dealt with immigration.

In 1922, in the midst of intense immigration, the Comite de Damas (Women’s Committee) was formed to assist the immigrants by providing jobs, medical care, loans, housing, and educational assistance. Lily Sourasky, Lily Rader, and Clara Weinstock were among those who headed it. The North American B’nai B’rith, which also committed itself to assisting in building a Jewish community in Mexico, had a representative who received immigrants at the Veracruz Port and helped them with housing and food. Women played a central role in these activities, which included running a hospital, a hostel and a soup kitchen.

The flow of immigration began to lessen from 1929 on, due to the world economic depression and immigration policies that limited the entry of foreign workers and showed preference for those with an ethnic and religious background similar to that of the Mexican population.

Three main groups constituted the Mexican Jewish community: Yiddish-speaking Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazim (Eastern Europe); Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardim (Mediterranean Europe); and Jews from the Levant, mostly of Syrian descent, divided into two sub-sectors (a) Halebis (or the Maguen David from Aleppo), and (b) Shamis (or the Monte Sinai from Damascus). Each group developed its own religious, cultural, and social organizations as well as educational institutions. The communal culture developed by Mexican Jewry had its core in a shared vision and discourse that emphasized unity, harmony, and consensus regarding groups, politics, and gender. However, the ethnic dimension constituted the main source of identity, thus relegating gender issues to minor importance.

Political Organization: Yiddish Radicalism and Zionism

Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazim from eastern Europe experienced differentiation around political and ideological axes. Women were not part of its leadership but they participated in all the cultural activities as well as in artistic and social endeavors of the vibrant immigrant community, such as the Young Men’s Hebrew Association, Tacuba 15, the I. L. Peretz Farein (later transformed into the Ydisher Kultur Geselschaft, which published the first Jewish newspaper, Mexikaner Idish Lebn), and the Radikaler Arbeter Tzenter, founded by the radical left in 1927. The Bundists founded the Kultur Zenter, which published the newspaper Unzer Lebn.

It is worth stressing the role played by women in the leftist organizations, specifically in the Gezelshaft far Birobidjan (Gezbir) established in 1936, which in the 1940s became Liga de Apoyo a la URSS (League for Support of the Soviet Union) and later the Liga Popular Israelita (Popular Israelite League). Women were active participants in these organizations and some were also active in the cultural and political organizations of the Mexican left. Among these were Buzia Kostov, Ruth Goldberg, Bluma Torenberg, Sara Maguidin, the sisters Fanny and Malka Rabel (respectively a very well-known painter and writer), and Rita Shvadsky, who was Leon Trotsky’s secretary during his Mexican exile.

Zionism was a significant area of ideological struggles and political differentiation in the Ashkenazi Jewish community. In 1922 there was an unsuccessful attempt to organize the Zionist movement; it was finally created in 1925. Liberals, Revisionist, Religious, and Poalei Zion each founded their own organizations. As early as 1935 the Organización Sionsita Sefaradi (Sepharadic Zionist Organization) was established. Women’s participation in the Zionist movement concentrated on social and cultural activities; Zionism became the springboard from which women established an important network of philanthropic organizations.

Philanthropy and Aid Societies

However, women’s main organizational framework in the institutional building process was that of aid societies. Most were comprised of women from the Ashkenazi sector, beginning with the Comité de Damas (Women’s Committee) in 1932. The same year saw the creation of the Froyen Farein (Women’s Union), devoted to assisting needy Jews. The Damas Pioneras (Pioneer Women), founded in 1935 by Sophie Udin, expanded its activities to tend to the diverse needs of poor Jewish and non-Jewish families. It later became Na’amat, which today is composed of eighteen groups and has a strong presence in Mexican hospitals and schools. The Women’s Union of Monte Sinai founded the Bikur Cholim in 1936, oriented mainly to assisting the sick. The next to be established, in 1938, was the Women’s International Zionist Organization (WIZO), which became a strong, modern organization, devoting itself to diverse areas of social assistance and educational support and maintaining a wide range of educational and cultural activities.

In 1941 the Comité Central de Damas (Women’s Central Committee) was founded. It later became the Consejo Mexicano de Mujeres Israelitas (Mexican Council of Israelite Women). An autonomous organization that assists the Comité Central Israelita de Mexico (Central Committee, the umbrella organization of Mexican Jewry), it is engaged in diverse social welfare endeavors. One of its main activities is fundraising for public schools, homeless shelters, and food distribution among the poor. Most of the above-mentioned organizations evolved from aid and welfare frameworks into full-fledged social and philanthropic institutions.

Mexican-Jewish Women in the Professional World

Scarcity of resources required Jewish women to work at their husbands or fathers’ sides, thus sharing the responsibilities of generating family income. Women worked in millinery, as seamstresses, selling at stalls in the local markets, or with their husbands in their small shops. When upward social mobility occurred, women became confined to their private spaces as housewives. The redefinition of their roles was expressed by identifying the strengthening of the home and maternal chores as a privileged feminine sphere.

Due partly to economic reasons and partly to fears of assimilation, women were limited in their academic and professional training, and the Yiddish-Hebrew Seminary for Teachers, founded in 1946, served as a substitute for university studies. While at the time of the foundation of the first Jewish (Ashkenazi) Day School in Mexico City in 1924, immigrant teachers were mainly males, women educated in seminaries in Eastern Europe also played a decisive role, contributing to the development and diversification of the educational system. They took an active part in the ideological struggles that determined the creation of new schools during the 1940s. This was the case with Rivke Golomb, Miryam Tjornitzky, Pauline Kovalsky, Frume Tartak, Shoshana Berkman, and Tamara Shein. Progressively, those who graduated from the Yiddish-Hebrew Seminary became the core of the Jewish teaching faculties at these schools. Working in the Jewish educational system became a socially accepted activity for women. Sephardim, Halebes, and Shamis founded their own day schools. While Jewish education became the central domain for women’s professional development, there were some notable exceptions. Among the first Jewish women to graduate from the university were Elizabeth Glantz and Gucha Bielak (in medicine) in the 1920s; Ruth Ferry became a gynecologist in the 1930s; Buzia Kostov (chemistry); Mira Yasinovsky (dentistry); Sara Dumont and F. Yavitz (pediatrics), and Henriette Begun (gynecology), all in the 1950s.

Community Demographics

In 2003 the Mexican Jewish population of approximately 40,000 had stable demographics and was relatively young, with 82.1 percent born and educated in Mexico. Its socio-demographic profile may be defined as transitional, with varying degrees of tradition and modern orientations. Generally speaking, the more traditionalist profile corresponds to the Maguen David and Monte Sinai communities and the more modernized to the Ashkenazi Jews. Non-affiliated individuals show a less traditionalist demographic behavior. The Mexican Jewish population is balanced in gender: 49.7 percent women and 50.3 percent men.

In the overall process of change, one of the main new social patterns is the increase in opportunities for interaction between the Jewish community and Mexican society. This is the result of the increasing number of Jews entering professional and public spheres, combined with a more open Mexican society that recognizes diversity and Otherness. While the community is still the main arena for identity building, both men and women explore new avenues and increase their visibility outside the community. Academia, the scientific and intellectual spheres, diverse professions, and public service are open areas for individual development.

While the family remains the main source of demographic, economic, and cultural reproduction, significant changes are evident. Sixty-two percent of the Mexican Jewish population over fifteen years old is married; three percent are divorced, and four percent widowed. The figures for Jewish women show a shift in the traditional family pattern. Of those between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four, 79.4 percent are single and twenty percent married. Fertility rates are dropping in all communities; women aged sixty-five and over had an average of 3.5 children, while those between 33 and 34 have 2.4. Today, the overall rate for the entire community is 2.7. Maguen David has a higher rate (3.6), followed by Monte Sinai (3.1).

There is a general trend in all the communities to delay marriage and childbearing while retaining an extremely low rate of intermarriage. In Mexico, only 3.1 percent of total marriages are mixed.

Approximately 18.1 percent of Jewish women are homemakers, but the figure is higher in Monte Sinai (25.8 percent) and lower in the Ashkenazi sector (15.2 percent). The educational and occupational profile of Jewish women is in accord with the general tendency towards increased professional and academic training. The previous trend of returning to the private-domestic realm as a result of upward mobility has been reversed, both as a result of diverse economic crises and out of individual decisions focused on self-fulfillment. Professions and academia—mainly the social sciences and humanities—are more common among Ashkenazi women; they are increasing in the Sepharadic and Middle Eastern communities. By and large, women still dominate the community’s Jewish educational network, which is composed of sixteen schools of which five are yeshivot (religious schools), with a total of 9,497 pupils in the 2003–2004 school year. Of the five elementary and high school yeshivot, one—Ateret Yosef—is for male pupils only, one—Bais Ya’akov—is exclusively for girls, and the other two—Keter Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah and Emunah—are for both boys and girls, who study in separate classes from kindergarten on. At the elementary yeshivah Or Ha-Hayyim which belongs to the Maguen David community, boys and girls study together until third grade, after which they separate into single-sex classes.

The above-mentioned trends have altered the traditional pattern of participation in women’s organizations: while the strength of Jewish women’s organizations appears to be diminishing among the younger generation, the highly diversified structure of the community in its different sectors offers a wide range of new areas for developing both social and cultural activities.

In the midst of the profound changes that are taking place, women continue to play a central role in the private-domestic sphere of identity building, where they act as agents of ritual transmission. Enhancing boundaries, such ritual reinforces ethnicity. In the Mexican community, data reveal a considerable number of observant women: 92.8 percent hold a A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.seder; 70.7 percent light Lit. "dedication." The 8-day "Festival of Lights" celebrated beginning on the 25th day of the Hebrew month of Kislev to commemorate the victory of the Jews over the Seleucid army in 164 B.C.E., the re-purification of the Temple and the miraculous eight days the Temple candelabrum remained lit from one cruse of undefiled oil which would have been enough to keep it burning for only one day.Hanukkah candles; 49 percent light SabbathShabbat candles; 48.7 percent eat Term used for ritually untainted food according to the laws of Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).kosher meat; 25 percent keep The Jewish dietary laws delineating the permissible types of food and methods of their preparation.kashrut at home. Mexico is undergoing both a process of religious pluralism and the rebirth of religiosity.

Mexican-Jewish Women Today

Cultural creativity reflects the new profile of women. Jewish writing by immigrants was at one time exclusively male. Jacobo Glantz, Moisés Rubinstein, Isaac Berliner, and Moisés Glikovsky are only a few of the best-known writers who contributed to the intense intellectual Jewish life in Mexico during the late 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. Yiddish was their language and literature became the means to explore their encounter with the new society. Today there is a veritable explosion of Jewish women writers whose work, written in Spanish, is recognized by society at large. They include poets such as Gloria Gervitz, Myriam Moscona and Esther Seligson; playwright Sabina Berman and novelists such as Margo Glantz, Angelina Muñiz, Nedda Anhalt, Ethel Krauze, Rosa Nissan, and Sara Sefchovich. Although Jewishness as a subject is not equally present in the work of all of them—and the gender dimension also varies widely—they all address specific aspects of their respective relationship with their Judaism and their gender identity. Most went through a process of rupture with the patterns, traditions, and values dominant in the Jewish community. In many cases the awareness of and commitment to their Jewish identity went hand in hand with their literary production, which provides an opportunity to explore the interaction between gender and ethnicity as cores of identity.

The new profiles of Jewish women in Mexico may be seen from the perspective of the dual character of the Mexican Jewish community. In its public dimension, it is an arena for Jewish creativity and activism in spite of its private character and traditional lack of visibility in the public realm. While the organized Jewish community is a space in which public energy is displayed and women’s organizations constitute a pillar of Jewish life, women have not achieved leading positions in the political communal structure. On the other hand, Jewish women continue to enter diverse spheres of activities in society at large, gradually achieving leading positions not only in the academic and scientific worlds but also in the public sphere, governmental institutions, and social and political organizations.

Jewish women today are part of a changing society where new generations, new profiles, and new activities are redefining their space, as well as the role and status of the organized Jewish community as a whole.

Bokser Liwerat, Judit and Paloma Cung Sulkin, eds Imágenes de un Encuentro. La presencia judía en México durante la primera mitad del siglo XX. México: 1992.

Bokser Liwerat, Judit. “La Inmigración Judía a México. Dinámica de un Encuentro.” In La Comunidad Judía en la Ciudad de México. México: 1999.

Bokser Liwerat, Judit. “Jewish Women in Mexico: Some Preliminary Reflections.” International research Conference on Jewish Women, Brandeis University: 1997.

Bokser Liwerant, Judit, and Alice Gojman Backal. Encuentro y Alteridad. La vida y la cultura judía en América Latina. México: 1999.

Cimet, Adina. Ashkenazi Jews in Mexico, Albany, New York: 1997.

Della Pergola, Sergio and Susana Lerner. La Población Judía de México: Perfil demográfico, Social y Cultural. México: 1995.

Gojman Backal, Alice (ed.). Generaciones Judías en México. Kehila Ashkenazi (1922–1992). México: 1999.

Hamui Halabe, Liz. Los Judíos de Alepo en México. México: 1989.

Kershenovich, Paulette. “Jewish Women in Mexico.” In Jewish Women 2000, edited by Helen Epstein. Hadassah Research Institute on Jewish Women, Waltham, MA: 1999.

Krause, Corinne. The Jews in Mexico: A History with Special Emphasis on the Period From 1857 to 1930. Pittsburgh: 1970.

Lesser, Harriet. A History of the Jewish Community in Mexico City 1912–1970. New York: 1972.