Old Yiddish Language and Literature

Women played a central role in the development and evolution of Old Yiddish literature. Old Yiddish literature was published with women’s literacy in mind, most nominally for women’s religious practice and learning. Two categories of works were undoubtedly addressed explicitly to females: the Frauenbüchlein, a genre that focuses on women’s three specific obligations (niddah, hallah, hadlakat ha-ner), and the supplicatory prayers called Tkhines. Besides their role as explicit or implicit readers, women played many other roles in and around Yiddish literature. They were actively engaged in Jewish book production, including typesetting, proofreading, and editing. We know of only two major works written by women in Yiddish: Meineket Rivkah by Rivkah bas meir Tiktiner and the memoirs of Glückel of Hameln.

Development and Evolution of Old Yiddish

The function of overall, natural, and spontaneous means of oral communication that Hebrew had lost by the second century of the Christian era was later performed by the Jewish vernaculars that originated in the languages of the areas of Jewish immigration. Yiddish became the spoken language of the Jews who settled in the German-speaking lands and of those who emigrated from there to other countries. An interactive bilingual Hebrew-Yiddish system developed and functioned throughout the Ashkenazi cultural area (which in the early modern period included Germany, Bohemia and Moravia, Poland-Lithuania, the Netherlands, Northern Italy until the beginning of the seventeenth century, and several locations within the Ottoman Empire), persisting until the Jewish Enlightenment; European movement during the 1770sHaskalah period. Yiddish, as everybody’s mother tongue, came naturally, while Hebrew had to be acquired by study. Although Hebrew reading skills were the first aim of the teaching program in Lit. "room." Old-style Jewish elementary school.heder—and we know that most girls acquired this reading ability either there or at home—no systematic teaching of the language took place in either framework, nor even in the yeshiva (from which girls were excluded). Thus, in order to master the language sufficiently to understand the Hebrew sources, much effort, devotion, and autodidactic diligence were required, and even more were necessary to engage in Hebrew creative writing. Those who achieved these skills owed them not to their formal education but to their willpower, talent, and perseverance, which also determined the degree of knowledge they reached. All the others did not attain the necessary language proficiency to understand a Hebrew book, and had in fact been taught to read a language they did not—or not competently—comprehend. We may assume that this group was a majority consisting of all the women (with rare exceptions), all the children and adolescents of both genders, and a considerable number of adult males in the Jewish population of the Yiddish-speaking area. Together with all the rest of the community, this significant part of the population was coached through the common stages of informal and formal education in Yiddish, which was until the Haskalah the only naturally spoken language of all the Jews throughout the Ashkenazi Lit. (Greek) "dispersion." The Jewish community, and its areas of residence, outside Erez Israel.Diaspora, regardless of gender, age, social, cultural or economic status. No wonder, then, that this vernacular, which everybody understood and most knew how to read, was the proper means to promote, enrich, and renew the knowledge of those unable to acquire it directly from the original sources. These boys and girls, “women and men that are like women for they do not understand loshn-koydesh,” were the principal target of Yiddish literature, the greatest part of which was intensely involved in the transmission of knowledge from the linguistically restrictive Hebrew corpus that continued to grow and develop.

The agents of the mediation between the less learned and the Hebrew sources were, for obvious reasons, learned men, mostly religious officials (kley kodesh) of some sort (including prominent rabbis). It was their view of the addressee’s capability to comprehend and learn, combined with their conception of his/her intellectual, spiritual, and behavioral needs and duties, that determined which were the segments of the Hebrew corpus to be transmitted and the appropriate methods of transmission.

Gender Roles and Yiddish Language Transmission

Apart from being the vehicle to Hebrew, a language the addressees knew how to read but did not understand, Yiddish was a vehicle to German, a language they understood but did not read. The associative link between the Latin characters and Christian priesthood resulted in their Jewish epithet, galkhes (from the Hebrew root gimmel-lamed-het for “shave,” referring to the priests’ tonsure) and in a kind of apprehension most Ashkenazi Jews shared until late in the eighteenth century. At times Yiddish functioned as vehicle to other languages, mainly Italian. In all these cases the mediators between the Jewish reader and the literature of the environment were the learned, most of them officials in charge of the community’s “external affairs.”

Yiddish Literature and its Gendered Audience

The variegated corpus of Old Yiddish literature that developed was intended for a broad heterogeneous public and open to all potential readers, “men and women, boys and girls, young and old,” as is clearly stipulated in the prefaces of many and diverse Yiddish books. Other works—including genres that would as a rule be addressed to male readers or to readers of both genders—add a distinct particular mention of the female addressee (“who should read this book on Saturdays and holidays instead of wasting her time reading other kinds of Yiddish books which are nothing but nonsense,” from the translation of the Pentateuch by Judah Loeb Bresch (15th–16th century, Cremona 1560). Elijah Levita (1468 or 1469–1549), who had not only preceded him in the distinct mention of the female addressee but made it exclusive in his translation of Psalms (Venice 1545), explains in the preface to his Bovo d’Antona (Isny, town in Bavaria, 1541) that the publication of this book is his first response to the requests of several ladies that he publish his Yiddish works. Several other Old Yiddish writers join him in calling themselves “servants of all pious women.”

Old Yiddish and Women’s Religious Practice

Despite the formulary and conventional nature of most of these, frequently rhymed, interpellations, they do reflect the general purpose of reaching as many kinds of readers as possible and presenting them all—and quite often women in the first place—with a large number of varied works. Thus, any literate woman (and most of them were) could read anything available in Yiddish, the language she spoke and understood: translations of the prayers, siddur (daily prayerbook), Mahzor (festival prayer book), selihot (penitential prayers), kinnot (lamentation dirges), and of other “oral” texts (such as the Grace after Meals and the A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover The "guide" to the Passover seder containing the Biblical and Talmudic texts read at the seder, as well as its traditional regimen of ritual performances.Haggadah); many kinds of partial or full renderings of the Bible, simple or complex, in prose or in rhyme, with short explanations or extensive commentaries, adapted and reworked into homiletic prose or structured into epic poetry (like the Shmuel Bukh or the Melokhim Bukh); numerous stories from the Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud, the A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).Midrash, and other sources, in large or small collections or in chapbooks containing only one story; translations and adaptations of Hebrew mussar (ethical) literature, from old to contemporary, alongside original compositions inspired and influenced by one or more works of this kind; updated adaptations of CustomMinhagim (books of customs) which, following the order of the yearly cycle, instruct the reader in whatever should be done at home and in the synagogue on the Sabbath, holidays, and other occasions such as weddings, circumcisions, burials, and periods of mourning; the bilingual Bentsherl, which provides not only the translation of Grace after Meals, but that of all texts employed at the ceremonies carried out at home throughout the year, including the Zemirot (table hymns). She could read the single parts of the Codification of basic Jewish Oral Law; edited and arranged by R. Judah ha-Nasi c. 200 C.E.Mishnah (Pirkei Avot; Ethics of the Fathers) and of the Talmud (Hilkhot derekh eretz; rules of proper conduct at home and in society) that were translated into Yiddish, and could also become acquainted with the innumerable The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhic elements that are blended into all the genres engaged in behavioral instruction, as well as with the copious Talmudic sayings that mingle there or are presented in rhymed versions in special collections. She could broaden her horizons by reading Yiddish translations: travelogues such as Sefer ha-Massa’ot (Book of Travels) by Benjamin of Tudela (second half of twelfth century) and Sibbuv ha-Olam (Around the World) by Pethahiah of Regensburg (twelfth century); historiographic works such as Josippon, a historical narrative written in Hebrew describing the period of the Second Temple, and Shevet Yehuda, a compilation of accounts of persecutions undergone by the Jews from the destruction of the Second Temple until the fifteenth century by Solomon Ibn Verga (second half of the fifteenth and first quarter of the sixteenth centuries); Zemah David (1592), a book dealing with Jewish and general history by David Gans (1541–1613). She could also read other works of these kinds composed originally in Yiddish (such as Moshe Prager’s Darkhei Zion (1650) and She’erit Yisrael, a short history of the Jews from the destruction of the Temple to 1743, the year of publication, by Menahem Mann Amelander (d. 1767). She could learn about current events by means of the so-called “historical” songs and be assisted by books of remedies in caring, for the health of her family. Hagiography, fables, amusing songs and poems, tales and stories and adaptations of romances of chivalry completed the available formative as well as informative Yiddish corpus that provided her with instruction, enlightenment and enjoyment.

Two categories of works were undoubtedly addressed explicitly to females: the Frauenbüchlein or Mitzves Noshim (Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.Seder A biblical or rabbinic commandment; also, a good deed.Mitzvot Nashim), a genre that focuses on women’s three specific obligations (Menstruation; the menstruant woman; ritual status of the menstruant woman.niddah, During the Temple period, the dough set aside to be given to the priests. In post-Temple times, a small piece of dough set aside and burnt. In common parlance, the braided loaves blessed and eaten on the Sabbath and Festivals.hallah, hadlakat ha-ner) and often deals with other aspects of a woman’s life and marital relations; and the supplicatory prayers called Tkhines. Two extremely popular Yiddish books of morals, Brantshpigl (Cracow, 1596) and Lev Tov (Prague, 1620), quite rightly called encyclopedias since they provide practical and spiritual guidance on multiple aspects of daily life, were constantly recommended to women by rabbis and teachers, although the Brantshpigl deals much more than the Lev Tov with matters directly concerning women. The most popular work of Old Yiddish literature, the Ze’enah u-Re’enah (Tsenerene), which was initially intended for men and women alike and explicitly addressed to both genders, in the course of time turned into the Jewish woman’s classic and essential reading.

Women’s Shaping of Old Yiddish Literature

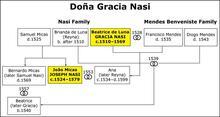

The part women played as distinct addressees must have caused the authors to take their needs and capabilities into consideration during the writing process, and thus influenced the character, methods, devices, and attitudes of Old Yiddish literature as a whole. The female reader also contributed directly or indirectly to the diffusion and promotion of Yiddish literary works. Individual women became recipients of various manuscripts: the Shmuel Bukh was copied for a certain Freidlen in Northern Italy; a book of customs was dedicated to a Venetian woman called Fradlina; a young man from Rovere visiting his aunt in Innsbruck wrote her a collection of about one hundred and twenty stories, and the father of a young Serlina in Venice commissioned a most comprehensive and variegated anthology for his daughter. Other works were dedicated to a specific woman who is cited in the published book as first among the addressed female public and who may well have been the author’s patron or the sponsor of the publication. This is true, for example, in the case of Ya’akov Heilprun, a poor melamed in charge of the instruction of the girls in his well-to-do family, who published three works he adapted from the Hebrew (Solomon Ibn Gabirol’s Keter Malkhut, a booklet called Dinim ve-Seder on “how meat should be soaked and salted and everything done properly,” and Orekh Yomim, a booklet of morals), dedicated to three of the women of his family (one of them actually a pupil of his, aged eight).

Besides their role as explicit or implicit, general or individual addressees, women played many other roles in and around Yiddish literature. The contemporary Jewish woman and her behavior are among the most frequent topics of discussion, and they are joined by a gallery of biblical and post-biblical, Jewish and non-Jewish heroines. Women of all these kinds appear in the illustrations of Yiddish books, especially—but not only—in the Minhagim, the Ze’enah u-Re’enah, the bentsherl, the Yiddish version of the Josippon. The titles of two booklets printed in Venice in 1552 and now lost—Istoria mi-Shalosh Nashim (a story of three women) and Mayse mi-Rivka (a story of Rebecca)—seem to attest to the first appearance of women as central characters in a Yiddish work. The women in Bovo d’Antona and Paris un’ Wiene, two sixteenth-century Yiddish adaptations from the Italian, play approximately the same role as in the original, but they sometimes either behave or are observed in a “Jewish” manner. The first amorous declaration in a Yiddish book appears in Paris un’ Wiene, where the author states that the reason for his writing is his deep love for a certain lady. This does not prevent him from inserting in his adaptation of the Italian source a long and detailed mocking tirade against women. This first Yiddish “anti-feminist manifesto” is joined by the first Yiddish story of romantic infidelity which is delivered by the Küh Bukh (a book of fables printed in Verona in 1594) and makes use of risqué allusions and expressions, the like of which can be found in Yiddish wedding songs of the time.

Women’s Engagement in Jewish Book Production

Women and young girls are also known to have been in various ways actively engaged in Jewish (Hebrew, Yiddish or both) book production as copyists, typesetters, proofreaders, editors, and publishers, usually operating in the printing shops of their fathers or husbands. Among the women engaged in typesetting (who were regularly called “ha-zetserin” or “ha-po’elet ha-zetserin” in both languages) during the early modern period we know of Gitl bas Yehuda Leib ben Alexander Cohen in Prague, Tsherna bas Menahem Nahum Meisels in Cracow, Sara bas Kalonymus Jaffe in Lublin and Rivka bas Yehuda Yudeles Katz in Wihelmsdorf, where she was joined by her sister Reikhl, who later moved first to Sulzbach and then to Furth, continuing her work there. Poems and short stories were published or edited in Prague by Peshl bas Zanvil, Serl bas Ya’akov ben Elia of Töplitz (who published her father’s poem), and Bela bas Ber ben Hizkiya Hurwitz, who published tkhines and was joined by Rahel bas Natan Raudnitz for the publication of some narrative prose. An edition of Selihot was paid for by Eidl bas Menahem Mendl of Prague in 1665; Mirl, the wife of the author and publisher Shabtai Bass, promoted the publication of an ethical will, and one Eydl bas Moyshe Mendls is believed to have published an abridgement of the Josippon (Cracow 1670).

Some of these women left more than the mention of their names in the books with which they were involved. Thus the sisters Ella and Gella, at the age of nine and almost twelve respectively, typeset in their father’s shop the Hebrew text of the prayerbook (the siddur) with its Yiddish translation. Both left their personal mark, one in 1696 and the other in 1710, in the moving little poems they composed and added to the colophon. Written in the first person, both poems deal with the girls’ thoughts and feelings.

A more comprehensive mark was left by Reyzl bas Yosef Halevi of Cracow, called after her husband “Reyzl reb Fishls.” While visiting Hanover she found the manuscript of the Yiddish rhymed Tehilim Bukh by R. Moshe Stendal. She copied it, brought it to Cracow, promoted its first publication there in 1586, and contributed a most interesting and well-written rhymed introduction of her own.

Legacy and Literary Works of Old Yiddish Women Writers

Other women’s voices can be heard in the extant wills some of them wrote, such as that written in Germany at the beginning of the eighteenth century by Rivka Sinzheim, who added moralizing exhortations, ethical commands and practical rules of behavior to her instructions for the disposition of her inheritance.

Women’s voices can also be heard loud and clear in the considerable number of Yiddish private letters written by women that have reached us from different times and places of the Ashkenazi Diaspora, most of which have not been published, or have been published but not researched. The oldest among them seems to be the letter written in Marburg in 1439 by the wife of one of the most prominent rabbis in Ashkenaz, Rabbi Israel ben Pethahiah Isserlein (1390–1460), in response to an inquiry on “women’s matters” sent with a messenger by a woman who asked to remain anonymous and who requested she be answered by the rabbi’s wife and not by the rabbi himself. Only six letters remain of those written in Jerusalem around the mid-sixteenth century by Rachel bas Avraham of Prague, the wife of Eliezer Sussman Tzarit, to her son in Cairo. In addition to containing copious information about the Ashkenazi community in Jerusalem at the time and about many interesting family occurrences, the letters reveal the thoughts and feelings, hopes and worries of an indigent old and sick widow who was born in Prague and lived some time in Venice before settling in Jerusalem.

Although their spoken language, Yiddish, was the only possible means of written expression of the great majority of Ashkenazi women in pre-modern times, we know of only two major works written by women: Meineket Rivkah by Rivkah bas meir Tiktiner and the memoirs of Glückel of Hameln (Glikl bas Leib Pinkerle). A greater number of minor Old Yiddish works written by women have reached us which seem to indicate that many more existed but have not survived or come to light. Several women are known to have composed one or more of the surviving supplicatory prayers (tkhines).

Ellus bas Mordekhai reb Michoels of Slutzk engaged in translating Hebrew works into Yiddish, while Bella Perlhefter wrote an extensive introduction to a book in memory of her deceased children.

Toybe bas Leyb Pitzker, the wife of Ya’akov Pan, is the author of a song bearing by way of title a kind of genre definition (Eyn sheyn lid), with a remark on its topicality (nay gemakht), its style (beloshn tkhine) and its melody (benign adir ayom ve-nora). Like many other so-called “historical” Yiddish songs, it deals with a current event. In fifty-one four-line stanzas, each with the refrain “fater kinig” (a Yiddish version of “avinu malkeinu”), the author offers a vivid description of a current plague in Prague (seventeenth century?) interspersed with moving invocations of the Creator’s mercy. The poem is the work of a fairly gifted poet who knows how to combine the description of the various aspects of the event with her moving supplications and render it all in a literary language abounding in translations and adaptations of Hebrew phrases.

Hana bas Yehuda Leib Katz, widow of Yitshak Ashkenazi, is the author of a booklet entitled Eyn hipshe droshe (A Charming [or Pretty] Sermon) which was printed in Amsterdam with no date, probably at the turn of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In fact the book consists of four sermons, the first three dealing with the sin of lashon ha-ra (gossip or slander) and the fourth with other “women’s sins” such as looking in the mirror and uncovering the hair. Written in rhymed prose, the sermons bear witness to the work of a distinctly learned woman, well versed in Jewish ethical literature and fairly well acquainted with Talmudic and Midrashic sources. The sermons follow a distinct pattern: they begin with an address to the readers (mostly, but not only, women) and some comments about the author, which are followed by a discussion of the topic richly interspersed with stories, illustrative examples and abundant quotations of many kinds, and conclude with an instructive moral. Three prayers are appended to the sermons—Hana’s own rhymed prayer for SabbathShabbat, and her translations of Mah Tovu and of a prayer for Rosh Hodesh Elul.

Hana’s and Toybe’s works were never reprinted; both survive in a single copy. Other women’s works appear not to have had even that good fortune.

Erik, Max. “The Brantshpigl—The Encyclopedia of the Jewish Woman in the Seventeenth Century.” Tsaytshrift (Minsk) 1 (1926): 173–177 (in Yiddish, another Yiddish version in: Erik, Max. A History of Yiddish Literature from Its Beginnings until the Haskalah Period.) Warsaw: 1928. Reprint: New York: 1979.

Korman, Ezra. Yiddish Women Poets: An Anthology. Chicago: 1927.

Niger, Shmuel. “Studies in the History of Yiddish Literature: Yiddish Literature and the Female Reader” (Yiddish). Der Pinkes, Vilna: 1913, 85–138.

Romer-Segal, Agnes. “Yiddish Literature and its Readers in the Sixteenth Century: Books in the Censor’s Lists, Mantua 1595” (Hebrew). Kiryat Sefer 53 (1978): 779–788.

Romer-Segal, Agnes. “Yiddish Works on Women’s Commandments in the sixteenth Century.” Studies in Yiddish Literature and Folklore (Research Projects of the Institute of Jewish Studies, Monograph Series, 7). The Hebrew University, Jerusalem: 1986, 37–59.

Shtif, Nokhem. “A Handwritten Yiddish Library in a Jewish Home in Venice in the Mid-Sixteenth Century” (Yiddish). Tsaytshrift (Minsk) 1 (1926): 141–150; 2–3 (1928): 525–544.

Turniansky, Chava. Language, Education and Knowledge among East European Jews. Unit 7 of Polin, The Jews of Eastern Europe: History and Culture (Hebrew). The Open University of Israel, Tel Aviv: 1994.

Turniansky, Chava. “Young Girls in Old Yiddish Literature” (Yiddish). In Jiddische Philologie, Festschrift fur Erika Timm, edited by Walter Röll and Simon Neuberg. Tübingen: 1999, 6–22.

Anonymous. “Le testament d’une juive au commencement du XVIIIe siecle.” Revue des Etudes Juives, 90–91 (1930): 146–160.