Orphanages in the United States

New York: Stettiner, Lambert, & Co., 1893

Institution: Hebraic Section, U.S. Library of Congress

In what was known as the "heyday of American orphanages" in the mid-nineteenth century, Jewish philanthropists, many of them women, feared that dependent Jewish children would become estranged from their religion by being taken in by non-Jewish institutions. Within these highly regimented and often isolating institutions, children received elementary education, religious instruction, and vocational training. For women, the latter, in keeping with nineteenth-century gender norms, centered on preparing them for marriage and motherhood. Eventually, several orphanages broadened their horizons and developed special programs to benefit female students they saw as intellectually gifted, encouraging them to attend college to become nurses or teachers. By 1940, most Jewish orphanages were absorbed into larger Jewish children's associations in many cities.

The Philadelphia Jewish Foster Home

In April 1855, the well-known Jewish philanthropist Rebecca Gratz led a group of Philadelphia Jewish women in founding the Jewish Foster Home, one of the earliest Jewish orphanages in the United States. The women saw it as their responsibility to provide for Jewish orphans and destitute children who should not be “left to the precarious chance of strangers’ beneficence and ... estranged from the religion of their fathers, left with a doubtful morality and with no feeling for the faith of Israel.”

The Philadelphia Jewish Foster Home was one of many Jewish orphanages established in the mid-nineteenth century in cities with significant Jewish populations. In this era, known as the “heyday of American orphanages,” Jewish philanthropists founded child-care institutions to accommodate growing numbers of dependent Jewish children who, it was feared, would otherwise be reared in non-Jewish asylums and lost to the Jewish community. Until 1940, when most American Jewish orphanages closed their doors, women were highly visible as founders, managers, staff members, and clients of the institutions.

Gratz and her associates remained at the helm of the Jewish Foster Home until 1874, when a male board of directors assumed control of its affairs. This pattern—of women founding orphanages, then displaced by men as the institutions grew in size and sophistication—was replicated at many other American orphanages, Jewish and non-Jewish, of the time. In the nineteenth century, however, orphanages were often described as a “women’s sphere of philanthropy.” The association of women with orphanages may be attributed to their traditional nurturing role, the greater involvement of women in charitable causes following the Civil War, and the community-based nature of orphanage work. Even when they did not occupy top positions, women were active in the day-to-day operation of the institutions, both as paid staff members and as volunteers. At the Philadelphia Jewish Foster Home, the New York Hebrew Sheltering Guardian Society, the Hebrew Orphan Asylum (HOA) of New York, and the Cleveland Jewish Orphan Asylum, among others, women were instrumental in fund-raising; providing clothing, equipment, and entertainment for the children; counseling youngsters, especially the girls; and supervising recently discharged orphanage wards.

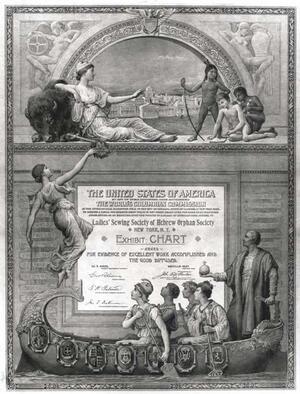

Institution: American Jewish Historical Society

Moreover, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Jewish orphanages served a largely female clientele. While orphanages initially housed poor youngsters from the German Jewish community, beginning in the last decades of the nineteenth century the great majority of their charges were the children of Eastern European immigrants, who arrived in large numbers between 1881 and 1924. Most of those housed in Jewish orphanages in this period were not full orphans, but rather “half orphans,” generally the children of widowed or deserted mothers.

These women generally tried to support their children for some time following a family crisis. They took in laundry and boarders, labored in the garment sweatshops that crowded immigrant ghettos, or sought work as cooks, peddlers, or scrubwomen. Some used the little insurance money left to them after their husbands’ deaths to establish small grocery or candy stores, which were often unsuccessful. Many left their young children in the care of relatives, neighbors, or older siblings while they went out to work. Hardly any organized child-care programs existed in the late nineteenth century, with the exception of scattered day nurseries, such as those sponsored by the United Hebrew Charities or the Temple Emanuel Sisterhood. The meager subsidies provided to destitute Jews by the United Hebrew Charities and other organizations offered little relief to families in desperate circumstances.

When the mother’s income proved insufficient, or relatives caring for a child could no longer do so because of illness, the child’s misbehavior, or other factors, it often became necessary to admit children to orphanages. For many women, this was a very painful decision, arrived at after much soul searching. Some vented their anger and frustration in the pages of the Yiddish press, or submitted applications for their children only to withdraw them after they had changed their minds. Parents who committed children to orphanages tended to divide up their families. In most cases, older youngsters went to work or remained at home to care for infants and small children, while school-age children were sent to orphanages, sometimes to different institutions.

Institutional Model

Within the institutions, children received elementary education, vocational training, and religious instruction. In keeping with nineteenth-century norms regarding male and female roles, the educational and vocational programs offered by Jewish orphanages were organized along stereotypical lines. For the most part, orphanage directors prepared boys for vocational and agricultural pursuits, and girls for marriage and motherhood, following temporary stints as dressmakers, milliners, or domestic servants. In addition to performing numerous household chores (generally justified as “vocational training”), youngsters received formal instruction in many areas. While boys were trained in carpentry, farming, shoemaking, ironwork, and printing, girls studied sewing, embroidery, dressmaking, “machine operating,” millinery, and, later, typing and stenography.

Following their discharge from the orphanage, many girls were placed in after-care programs, such as the New York Clara de Hirsch Home, the New York Hebrew Orphan Asylum’s “Friendly Home” (in which a small group of girls boarded for several months and mastered domestic skills), or a similar facility managed by the Philadelphia Jewish Foster Home. In establishing such programs, orphanage directors sought to prepare their female wards for family life and enable them to earn a livelihood before marriage. These sheltered environments and close personal supervision of female graduates would, it was hoped, protect young girls from the dangers of urban life, especially prostitution, then a significant problem in immigrant Jewish ghettos.

Expansion in Programs

While Jewish orphanages generally succeeded in rearing their wards to be self-supporting, they also limited the young people’s sights by directing them to specific fields. For example, they encouraged girls to enter domestic service, an occupation viewed as safe and appropriate for lower-class women in this period. Immigrant Jewish girls, however, tended to reject such positions, regarding them as humiliating. By the turn of the twentieth century, Jewish orphanage directors increasingly recognized the need to widen their wards’ horizons, by providing opportunities for higher education to the more talented youngsters. Many Jewish orphanages established scholarship funds to assist students attending high school and college, trade, and professional schools.

At a time when young American women began to attend college in greater numbers, several Jewish orphanages developed special programs to benefit female students. Intellectually gifted girls were encouraged to attend college and become nurses or teachers, some of whom later returned to the orphanages as staff. By 1921, for example, a number of Hebrew Orphan Asylum girls attended Hunter College and Columbia University’s Teachers College, and quite a few were enrolled in high school and evening college professional courses. The Jewish Foster Home’s Pfaelzer Fund, directed entirely by women, provided gifted girls with scholarships to various industrial, professional, or artistic programs.

Religious Mission

Beyond general and vocational education, Jewish orphanage directors saw it as their mission to train their wards to serve the Jewish community as rabbis and teachers. They sent qualified boys to the Hebrew Union College (Reform) or Jewish Theological Seminary (Conservative) to prepare for the rabbinate. Many girls also received higher Jewish education. In 1896, Kaufmann Kohler, a prominent Reform rabbi and instructor at the HOA, urged that promising HOA girls, whom he found to be “as clever and bright as the boys, if not more so,” be trained as Sunday school teachers.

Despite their notable successes in some areas, including education, many Jewish orphanages in the nineteenth century were highly regimented institutions that isolated children from the outside world. Most tragically, Jewish orphanage directors, in their zeal to Americanize their wards, often alienated them from their largely foreign-born parents. Many orphanage wards had difficulty relating to their families following discharge. As one Brooklyn Hebrew Orphan Asylum alumnus put it, “[My mother] was almost like a stranger to me. I didn’t like the kind of food she cooked because I had never eaten it in the Home.... Also she spoke Yiddish most of the time, and I didn’t understand that. I think the Fellows should see their parents more while they are in the Home.”

Legacy

The early twentieth century witnessed a significant liberalization of orphanage policies in all areas, including parental visitation. Increasingly, Jewish orphanages served a changing population, composed largely of emotionally disturbed and socially maladjusted youngsters. With the expansion of foster care, the orphanage increasingly became a thing of the past. Around 1940, most Jewish orphanages were absorbed into umbrella organizations, known as Jewish children’s associations, in many cities.

Significant numbers of American Jews spent major portions of their childhoods in Jewish orphanages. Moreover, the institutions’ influence reached beyond the youngsters themselves to their parents and relatives, as well as to staff members and those who supported the institutions financially and otherwise. Orphanage stories offer valuable insights into the lives of both middle- and lower-class women in a critical period of American Jewish history.

Bank, Jules. “A Study of 108 Boys Discharged from the Brooklyn Hebrew Orphan Asylum, 1924–1929. Based on Case Records and Interviews.” M.A. thesis, Graduate School for Jewish Social Work (1936);

Baum, Charlotte, Paula Hyman, and Sonya Michel. The Jewish Woman in America (1976);

Bernard, Jacqueline. The Children You Gave Us: A History of 150 of Service to Children (1973);

Brooklyn Hebrew Orphan Asylum, Annual Reports, 1880–1925, and Hebrew Sheltering Guardian Society, Annual Reports and Minutes, 1880–1925. Collections, Jewish Division, New York Public Library;

Child Care Study, NYC, 1922, and Child Care Study, Philadelphia, 1920, and Child Care Study, Philadelphia, 1924. Bureau of Jewish Social Research, New York Kehillah;

Cleveland Jewish Orphan Asylum. Annual Reports, 1880–1925, and Records, 1868–1957. Cleveland Jewish Orphan Asylum Manuscript Collection. Cleveland Jewish Archives, Western Reserve Historical Society;

Fleischman, S.M. The History of the Jewish Foster Home and Orphan Asylum of Philadelphia, 1855–1905 (1905);

Friedman, Reena Sigman. “‘Send Me My Husband Who Lives in New York City’: Husband Desertion in the American Jewish Immigrant Community.” Jewish Social Studies (Winter 1982): 1–18;

Goren, Arthur. New York Jews and the Quest for Community: The Kehillah Experiment, 1908–1922 (1970);

Hebrew Orphan Asylum. Annual Reports, 1860–1925, and Records, 1880–1925, and Council of Jewish Federations and Welfare Funds Papers. Hebrew Orphan Asylum Manuscript Collection. American Jewish Historical Society;

Lerner, Gerda. The Majority Finds Its Past: Placing Women in History (1979);

Philadelphia Jewish Foster Home. Annual Reports, 1880–1925, and Records, 1855–1929, and Association for Jewish Children Records. Philadelphia Jewish Foster Home Manuscript Collection. Philadelphia Jewish Archives, Balch Institute;

Polster, Gary. “Member of the Herd: Growing Up in the Cleveland Jewish Orphan Asylum, 1868–1919.” Ph.D. diss., Case Western Reserve University (1984);

Ross, Catherine. “Society’s Children: The Care of Indigent Youngsters in New York City, 1875–1903.” Ph.D. diss., Yale University (1977);

Sharlitt, Michael. As I Remember: The Home In My Heart (1959).