Post-Biblical and Rabbinic Women

In antiquity, the treatment of women drew from patriarchal biblical traditions. Despite a few notable exceptions, women had minimal legal rights, including the inability to inherit land. While some customs, such as levirate marriage, declined in popularity in the Common Era, other biblical traditions including menstruation laws became more stringent and expansive. Women were banned from the official temple cult, but they were able to hold office in Second Temple times. Women also became members of alternative Jewish denominations, such as the Dead Sea Sect. But they were also negatively associated with witchcraft, perhaps due to their common involvement in the medical profession. As rabbinic material was codified, control over women increased, although the literature was not exclusively restrictive towards women.

In post-biblical Jewish antiquity women were not viewed as equal to men or as full Jews. In this, Jews were no different from their various Greco-Roman, Semitic, or Egyptian neighbors. The difference lies in the explanation Jews gave to their views. All Jews of late antiquity (whether they belonged to a sect, such as the Pharisees or the Dead Sea Sect or were simply ordinary people, often disparagingly termed in the sources as “the people of the land—am ha-arez”) considered women’s position in Judaism as determined by the injunctions of the Old Testament. Their subordinate position was viewed as emanating from Eve’s role in the creation narrative, both as created second aryand as guilty of the original sin.

Story of Eve

Thus, the second century BCE Palestinian sage Ben Sira bitterly laments women’s role in bringing death to the world (Ben Sira 25:24), referring to the incident in the Garden of Eden. A Jewish pseudepigraphic composition, usually referred to as the Book of Adam and Eve, greatly elaborates on this theme, constantly reiterating woman’s involvement in man’s fall, her guilt, and his accusations against her. Later midrashic literature continues in the same vein: women are eternally punished for their involvement in the original sin. Women not only suffer giving birth and are subjected to their husbands (as already mandated in the Bible), but they are also locked up at home as in a prison, go out with their heads covered, and must separate from their husbands while menstruating (Avot de-Rabbi Nathan version B, 42). Even the special commandments reserved for women—lighting the Sabbath candles, setting aside the During the Temple period, the dough set aside to be given to the priests. In post-Temple times, a small piece of dough set aside and burnt. In common parlance, the braided loaves blessed and eaten on the Sabbath and Festivals.hallah portion, and menstruation (Menstruation; the menstruant woman; ritual status of the menstruant woman.niddah)—are viewed as punishments for that sin (e.g. The interpretations and elaborations of the Mishnah by the amora'im in the academies of Erez Israel. Editing completed c. 500 C.E.Jerusalem Talmud: SabbathShabbat 2:4, 5b). The Codification of basic Jewish Oral Law; edited and arranged by R. Judah ha-Nasi c. 200 C.E.Mishnah Shabbat 2:6 states that women who transgress keeping these commandments will die in childbirth.

Contemporary concerns and Hellenistic influence were brought to bear on the biblical justification for women’s subordination. In one A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrash the rabbis quite transparently compared the biblical creation myth of woman as secondary and the cause of humankind’s expulsion from Eden with the Greek Pandora myth, in which woman is also seen as created secondary and the source of all the evils of the world. In the Greek myth, the first woman was given a box, which she was told not to open. However, her curiosity got the better of her, releasing all the evils into the world, including death.

In one parable Eve is compared to a woman whose husband gave her all his property save for one barrel, which she was not supposed to open. Unable to contain her curiosity, she opened it and found the barrel full of scorpions and snakes which bit her and caused her agony (Genesis Rabbah 19:10). This can be compared, the rabbis claim, to the story of Adam and Eve, who were permitted to eat from all trees but the tree of knowledge. However, Eve did eat from it and as a consequence she and Adam both suffered and subsequently died.

Legal Position

Jewish women’s legal position was also based on the Hebrew Bible, particularly on injunctions mentioned in the legal sections of the Pentateuch. Biblical law in general was of Semitic origins and supported a society that upheld polygyny and bride-price marriages. However, internal developments, as well as the influence of the western civilizations under whose aegis the Jews had come beginning with the third century BCE (the Greeks and then the Romans), tended toward monogyny and dowry marriages. Thus, some of the biblical injunctions associated with women came under scrutiny.

Numbers 27 (1–11) discusses specifically the Jewish daughter’s right to inherit from her father. The daughters of Zelophehad, who had no brothers, demanded of Moses recognition of their right to inherit, since otherwise their father’s estate would be lost to the family. Moses brought their case before the Lord. And the Lord said to Moses, that the plea of Zelophehad’s daughters is just, but the decision clearly stated that Jewish daughters could inherit from their fathers only where there were no sons.

Although this ruling is often upheld as an example for an eme,ndation made in biblical law in favor of women, it was certainly not egalitarian since it denied other daughters the right to inherit. It also prevented further egalitarian legislation in this field in antiquity, since in this ruling the Bible itself appeared to make a clear distinction between sons and daughters. Thus Second Temple Pharisees, in their legal dispute with their Sadducee opponents (Jerusalem Talmud [JT]: Bava Batra 8:1, 16a), zealously upheld this ruling as the final word on the matter. Their opponents, on the other hand, were probably influenced by the Greco-Roman world, in which women were equal heirs to their fathers, when they claimed that the law was unfair and therefore could not reflect divine intention. Their reliance on the sages of the gentiles (hakhme goyim) is stated explicitly in the source. Yet the Pharisee position which, in this case, upheld biblical law, won the day.

Marriage between a widow whose husband died childless (the yevamah) and the brother of the deceased (the yavam or levir).Levirate marriage is the obligation of a childless widow to marry her dead husband’s brother. This custom, presented in Deuteronomy 25:5–10, was initially explained as an act of charity toward the dead husband and brother. The rabbis of late antiquity adopted the same attitude. An entire tractate in the Mishnah (Yevamot) is devoted to the intricacies of this institution. Praise for its merits was still voiced in the fourth- through sixth-century CE Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud. Rabbi Yose ben Halafta (mid-second century CE), who took his sister-in-law in levirate marriage, is greatly praised for his action (e.g. JT:Yevamot 1:1, 2b).

However, the Bible also includes, albeit grudgingly, a move to release the levirate bride from her levir. This action, halizah, requires a ritual during which the reluctant levir is denigrated: his intended spits in his face and removes his shoe. Despite praise for levirate marriage, it was almost completely abandoned by the end of the second century CE as it often clashed with the move toward monogyny. One talmudic text suspects all levirate matches as emanating from lust of the partners, and likens the offspring of such unions to bastards (mamzerim— The discussions and elaborations by the amora'im of Babylon on the Mishnah between early 3rd and late 5th c. C.E.; it is the foundation of Jewish Law and has halakhic supremacy over the Jerusalem Talmud.Babylonian Talmud [BT]:Yevamot 39b). The rabbis ceased to view halizah as negative and maintained that in their day halizah was the norm rather than the exception. Thus, we see how in some cases post-biblical Judaism maintained biblical law without maintaining its spirit.

Some biblical laws were greatly expanded. One example is the laws of menstruation (niddah), which are discussed in Leviticus 15:19–30. It is not clear whether these laws originally applied to the entire population or were intended for the separation and special elevation of the priestly caste. In the Second Temple period, however, the laws of niddah were strictly upheld by most segments of Jewish society and greatly elaborated upon by the rabbis in the Mishnah. They state specifically that the Sadducees and Samaritans observed these rites differently (Mishnah Niddah 4:1–2), obviously indicating that control of women and their actions was a site of sectarian struggle.

Although most purity regulations were abandoned after the destruction of the Temple, niddah regulations were upheld and even expanded. For example, the rabbis demanded that a woman examine her internal parts frequently to discover whether she was bleeding, since they maintained that everything a woman touched between one examination, when she discovered herself pure, and the next, when she was found to be menstruating, was retroactively defiled (Mishnah Niddah 1:2). They demanded that women who ceased to bleed refrain from sexual intercourse with their husbands for a further seven “clean” days, to insure absolutely that they not defile them (BT Niddah 33). This phenomenon suggests a mechanism by which the rabbis hoped to maintain control over women’s unruly biological functions.

Another biblical institution was the test of the bitter water (Suspected adulteresssotah), according to which a wife suspected of infidelity could be tested by a magical procedure in the Jerusalem Temple (Numbers 5:11–30). This practice was still in use in Second Temple times, but was strongly criticized and perhaps even abandoned altogether toward the end of the period, reportedly due to Rabban Johanan ben Zakkai, the leading rabbi of the last decade before the destruction of the Temple (Mishnah Sotah 9:9). Whether the report is correct or a retroactive projection on earlier times is not clear.

In any case, the problematic nature of this institution may be reflected by the fact that the biblical text of the sotah was inscribed on a golden tablet and donated to the Temple toward the middle of the first century BCE. The donation, which came from an influential Jewish convert and foreign queen, Helene, was probably a political statement on the sotah debate (Mishnah Yoma 3:10). This does not necessarily mean that women supported the procedure while men rejected it. It suggests, more probably, that this specific woman—Helene—and this man—Rabban Johanan ben Zakkai—were to be found on two different sides of the debate. In any case, after the destruction of the Temple the institution was often viewed as ineffective. Guilty women, it was maintained, could withstand the test if they had a meritorious past (Mishnah Sotah 3:4). Wives of men guilty of the same transgressions could not be tested by the water (Mishnah Sotah 5:1). This confirms that rabbinic texts represent Rabban Johanan ben Zakkai’s side in the debate.

There were also issues associated with women’s position which had not been dealt with by the biblical legislator. Second Temple and Talmudic Judaism innovated greatly in these fields. Thus, according to rabbinic sources, the rabbinic leader Simeon ben Shatah (first century BCE) reformed the Jewish marriage contract (Marriage document (in Aramaic) dictating husband's personal and financial obligations to his wife.ketubbah), in favor of the woman during the Second Temple period ((Aramaic) A work containing a collection of tanna'itic beraitot, organized into a series of tractates each of which parallels a tractate of the Mishnah.Tosefta Ketubbot 12:1; JT Ketubbot 8:11, 32b–c; BT Ketubbot 82b).

The intent of his reform was that several of the woman’s rights in marriage be made legally binding by a written document. It made support for a widowed or divorced wife part of the legal system and not an act of charity. Marriage contracts were legal documents produced by some of the societies the Jews came in contact with, such as the Greeks.

Furthermore, this institution was a viable one and not a mere rabbinic fiction. Contemporaneous Jewish marriage documents have been discovered in the Judaean Desert. Many of these display a plethora of traits that are incompatible with the rabbinic ketubbah but can be easily traced to Greek and Roman legal tradition. Others indicate the early legal and historical (rather than literary) basis of this seemingly rabbinic institution, since most of these documents pre-date the Mishnah by several decades.

The Cult and Public Life

During the First Temple period women may have held some sacred offices, but with the final victory of monotheism in Judaism at the beginning of the Second Temple period women were completely excluded from officiating in Jewish cultic practices. Their secondary role in the cultus was exemplified by the existence of a women’s court in the Jerusalem Temple, beyond which women were not allowed to proceed into the Inner Court unless they were bringing a special sacrifice (Josephus, Wars 5:198–9, Mishnah Middot 2:5–6).

Women had no official role in the Temple staff. The only mention of women in association with the running of the Temple is that of weavers of the Temple curtains (Tosefta Shekalim 2:6). Weaving in general was a traditional feminine occupation, and women weavers producing sacred garments were present in many Greek Temples at the time. Nevertheless, in our sources even this minor appearance of women on the scene of the Temple was played down. Thus, while the Tosefta clearly mentions the women weavers (Tosefta Shekalim 2:6), its more authoritative counterpart, the Mishnah, in a parallel passage mentions only the male supervisor of these activities (Mishnah Shekalim 5:1).

After the destruction of the Temple, the exclusion of women from Jewish religious activities continued with rabbinic legislation, which exempted them from all time-bound commandments such as the daily prayer, the wearing of phylacteries, residing in the Booth erected for residence during the holiday of Sukkot.Sukkah or going on pilgrimages (Mishnah Kiddushin 1:7). These commandments in contrast to others which are not time-bound, are clearly cultic in nature. Women’s exclusion from them meant their expulsion from Jewish cultic life.

However, outside the official temple cult, women were not legally barred from any office and took part in various public functions. This can be exemplified first and foremost by the fact that in the most Jewish dynasty of Second Temple times—the Hasmoneans—a woman served as queen (Shelamziyyon Alexandra, 76–67 BCE—Josephus, Ant. 13: 407–32). She inherited the throne from her husband Alexander Yannai (b. 125 BCE, reigned 103–76 BCE), in the same way that her contemporary Egyptian-Ptolemaic queens gained their thrones.

In an earlier episode, Josephus (the main historical source for the queen’s reign) tells us that Shelamziyyon’s father-in-law, John Hyrcanus (b. 167 BCE, reigned 135–104 BCE) had attempted to appoint his wife queen some thirty years earlier but had failed in his attempt (Josephus, Ant. 13:302). From this we may surmise that in the Hasmonean dynasty a struggle took place between those who maintained that the queen should succeed her husband, and others who believed it was a son’s right. Queenship was obviously a secular office, but it is significant that a woman held this office because the monarch (in this case the queen) was hierarchically positioned above the religious establishment. Thus, it was the queen who decided who would serve as high priest, and not vice versa. Unsurprisingly, she nominated her elder son Hyrcanus II to the office.

Sources—particularly from the Lit. (Greek) "dispersion." The Jewish community, and its areas of residence, outside Erez Israel.Diaspora—indicate that when the synagogue, which was not included in the biblical cultic system, took over the cultic functions of the Temple after its destruction, women played critical roles in that institution alongside men. Inscriptional evidence indicates that some women, like men, held office and carried titles such as Archisynagogos (head of synagogue), Presbyter (elder), or Mater Synagogos (mother of the synagogue).

Alternative religious outlets were also available to women during Temple times. For example, they took an active interest in the activities of Jewish sects and could join some as full-fledged members. Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BCE–50 CE) describes the Diaspora ascetic sect of the Thrapeutics. This Jewish-Egyptian group, which chose to withdraw from human society and live a life of contemplation in the desert, consisted of both male and female members, whose burdens and responsibilities were of equal value. The nature of the interaction between the sexes in this sect is best described as “equal but separate” (Philo, De Vita Contemplativa).

The Palestinian Pharisee sect seems to have encouraged women’s involvement and support, which were sponsored not only by the Hasmonean queen already mentioned, but also by Herodian women and by women of the high-priestly families. Women were probably not merely sympathetic supporters but also active members of the group. Thus, rabbinic texts dealing with the havurah (apparently the Pharisee table-fellowship) applied equal demands to men and women (Tosefta Demai 2:16–17). The invisibility of women in Pharisaism, as reflected in most rabbinic texts, results from a deliberate attempt of the later rabbis to erase women’s presence and, indeed, all sectarian characteristics from the earlier Pharisees.

Women were perhaps also involved in the activities of the Dead Sea Sect, whose documents, for example, mention women elders and female scribes. They also discuss in detail laws applying to all family members; one document describes the responsibility of the sectarian wife to give evidence against her husband in cases where his behavior transgressed sectarian law (see below). Female skeletons, discovered in the cemetery of Qumran, were probably those of members of the Dead Sea Sect buried in the communal cemetery.

Women were most probably also involved with the various sectarian organizations that participated in the revolt against Rome in the years 66–73 CE, of which the Zealots were but one. Most of our evidence for women’s participation in these groups refers to that which followed Simeon bar Giora, the Jewish military leader in the war against Rome (66–70 CE). We hear both that women constituted part of his entourage (Josephus, Wars, 4.505) and that his wife was one of his constant companions (Ibid., 4.538). But more circumstantial evidence is also available.

Both the Jewish historian Josephus and Tacitus, a Roman, refer to women who joined in the fighting against Rome (Josephus, Wars, 3.303; Tacitus, Histories 5.13.3). Women were also present on Masada and took part in the famous suicide pact made by the defenders of the fortress (Josephus, Wars, 7.393). The two main ideological innovations of the zealot movement of the revolt against Rome were neither explicitly nor implicitly denied to women, instead, the Second Temple Jewish literature women serve as prime role models for both.

One characteristic is personal zealotry, in which an individual takes it upon themself to deliver his or her people by the assassination of a public figure. The best literary example of such an action remains that of the female hero Judith, who, by slaying the enemy general Holofernes, delivered her people from foreign conquest. The second ideology typical of the zealot movement was the idea of self-afflicted martyrdom, namely suicide rather than subjugation to the enemy. This, as we know, was practiced by Jews throughout the war against Rome and is exemplified on Masada. The only literary role model for this action from Second Temple times is the mother of the seven Maccabean martyrs, as she is portrayed in the fourth book of Maccabees, who chooses to take her own life rather than subject herself to the will of the Greek ruler (4 Maccabees 17:1).

Finally, there is little doubt that Jewish women became important supporters of the Jesus movement prior to the Crucifixion. Jesus’s followers included women. When he was arrested, all his male supporters deserted him; it was women who cared for his burial and were thus the first witnesses to his resurrection.

Women’s support for sectarian organizations and nascent religious and ideological movements is a universal-social phenomenon. We can therefore interpret this phenomenon within Judaism of the Second Temple period as a means of social and vocational expression open to oppressed groups (such as women), who were barred from participating in the central and official power and influence systems. Once some of these sects, primarily the Pharisees and Christianity, became part of the establishment, they legislated against women holding positions of equality and power. Likewise, they attempted to erase any traces of the support women had once rendered them. Women’s support in the eyes of the establishment was generally viewed as embarrassing.

Women are also often portrayed in the sources as primary agents of magic. They are accused of being witches and practicing sorcery (e.g. JT Sanhedrin 7:19, 25d; BT Sanhedrin 67a). Most stories of witchcraft in rabbinic literature involve women and most magicians described therein are female. One tradition mentions a leader of sorceresses (BT Pesahim 110a). Another tells of a woman whose healing powers are a guild secret (JT Shabbat 14:4, 14d).

Perhaps this guild is none other than the association mentioned so negatively in the former source. Rather than accepting these descriptions as true, or discarding them as disparaging and totally false, we should perceive them as the sources’ unsympathetic (male) interpretation and often as a misunderstanding of women’s religious and even professional expression, of which we now know very little.

It seems that women’s fairly intensive involvement in the medical profession was one of the causes for this view. Because women were midwives and cooks, they often understood physical processes and chemical dietary combinations that placed them ideally as potential healers. When their healing activities failed, however, failures were often perceived as malicious malpractice and sorcery. At one point in Second Temple history the disparaging attitude toward women’s activity seems to have erupted into a full-scale witch-hunt. This event, which probably took place during the reign of Queen Shelamziyyon, is recorded laconically in rabbinic literature. The Mishnah states simply that Simeon ben Shatah (apparently Shelamziyyon’s Pharisee advisor) hanged eighty women in Ashkelon (Mishnah Sanhedrin 6:4). The Yerushalmi, however, specifically identifies the women as witches (JT Sanhedrin 6:9, 23c). Since witch-hunts are a universal phenomenon, one should assume a historical kernel for this story.

The above comments are not intended to obscure the fact that women usually did not frequent public spaces or did not often fulfill important offices. The rabbinic sources had to work hard to bring the minority of independent and assertive women under control, but obviously most Jewish women, then as now, stayed at home and kept house. For these women the rabbinic sources are not only prescriptive, but also descriptive.

Women and the Rabbis

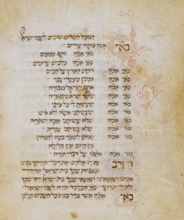

The most complete corpus dealing with women’s position in Judaism in antiquity is found in the Order of Women in the Mishnah (edited ca. 200 CE), a collection which is an attempt to neatly organize the messy issue of patriarchal control of women in Jewish law. In consequence, rabbinic literature, particularly the Mishnah, is more restrictive toward women’s participation in public and private life than what seems to emerge from Second Temple sources. For example, rabbinic literature excludes women altogether as witnesses in a court of law (Mishnah The Jewish New Year, held on the first and second days of the Hebrew month of Tishrei. Referred to alternatively as the "Day of Judgement" and the "Day of Blowing" (of the shofar).Rosh Ha-Shanah 1:8; Sifre Deuteronomy 190).

In the Second Temple period, however, women apparently did serve in such a capacity. For example, one Dead Sea Sect text suggests that wives were encouraged to give evidence against their husbands in the Sect’s tribunal (1Qsa I 10–11). This was not a very feminist piece of legislation, since it was intended to instill in female as well as male members the notion that loyalty to the sect takes priority over loyalty to one’s spouse. Yet it indicates that on the question of women as witnesses, what was later considered as time honored Jewish tradition was unknown as such to the Dead Sea Sect. In support of this claim, one may add that in Herod’s court women are often portrayed as giving evidence in important trials (e.g., Josephus, Ant., 17:65).

Another example has to do with divorce. The right to divorce in the Bible is described incidentally, as part of the law that forbids a man to remarry his divorced wife after she was married to another, was then divorced or widowed (Deuteronomy 24:1–4). Thus, the right to divorce is not formulated as an absolute prerogative of the husband. Rabbinic literature, however, leaves one in no doubt that divorce was a unilateral action, reserved to the husband alone (Mishnah Writ of (religious) divorceGittin 9:3).

Nevertheless, one of the documents discovered in the Judaean Desert seems to indicate that outside of rabbinic circles women could and did initiate divorce proceedings. In this document a woman by the name of Shelamziyyon daughter of Joseph of Ein Gedi sends her husband, Eleazar son of Hananiah, a document terminating their marriage. The words she uses to describe the transaction are “a bill of divorce and release,” just as in the mishnaic text (Mishnah Gittin 9:3). This document is one example of how taking rabbinic literature alone as a reflection of social reality may create misconceptions.

The codification of the rabbinic material also brought about a tightening of control over women within rabbinic circles themselves. It is well known that the entire corpus of rulings suggested by Beit Shammai was rejected wholesale by the descendents of Beit Hillel who edited the Mishnah. What is less known is that in general, while this corpus may have displayed a more somber view of life, it at the same time presented a more benign view of the position of women in Judaism.

Beit Shammai supported a woman’s right to run her business transactions independently (Mishnah Ketubbot 8:1). They argued for the reliability of a widow’s testimony regarding the death of her husband and thus demanded a full payment of her wedding settlement (Mishnah Eduyyot 1:12). And since they accepted the unilateral nature of rabbinic divorce, they limited considerably the grounds on which a husband could sue for divorce (Mishnah Gittin 9:10). Thus, the rejection of the entire Beit Shammai corpus was not beneficial to women’s legal position within the canons of Judaism.

Other examples of the curtailment of women’s rights within rabbinic literature are also evident. One rabbinic composition, for example, using the masculine language of the biblical text (“King”—Deuteronomy 17:14), attempted to make queenship illegal (Sifre Deuteronomy 157). Interestingly, the same composition mentions with great admiration the reign of Queen Shelamziyyon (Sifre Deuteronomy 42). Such contradictions, however, are hardly surprising within a literature that is drastically altering its agenda and attempting to conceal earlier preferences.

Rabbinic literature, however, is not uniform, and a tightening of control may be evident in one of its compositions, while the reverse may be detected in another. Judith Hauptman has shown that while the Mishnah is restrictive, its sister, the Tosefta, suggests a much less rigid attitude toward women’s position. For example, while the Mishnah reserves procreation as a commandment to men alone, the Tosefta can envision a situation where women are equally commanded to fulfil it. The restrictions are not blatant but are usually carried out on a subtle, editorial level. A scratching of the surface can reveal it to all. Unlike the Mishnah, the more benign Tosefta never became canonized and its rulings never became law.

The rabbis who composed rabbinic literature were, in the main, scholars who created a society that valued learning above all other qualities. Learning became an important status symbol and a means of achieving social mobility. It endowed its initiates with social privileges, which the rabbis appropriated to themselves. For this reason, the rabbis’ attitude toward women and the learning of Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah is of special importance.

To begin with, rabbinic literature displays some ambivalence on this question. The Mishnah presents the issue as a dispute between two sages. Yet one rabbi is specifically quoted as supportive of teaching daughters Torah (Mishnah Sotah 3:4). The more lenient Tosefta even suggests that women were not altogether absent from rabbinic academies. Thus a woman by the name of Beruryah is mentioned as formulating a The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhic principle (Tosefta Kelim Bava Metzia 1:6).

However, by the time that the Babylonian Talmud came to be composed this presence was so unique that the rabbis transformed Beruryah into a superhuman scholar (BT Pesahim 62b). Nevertheless, the rabbis’ restrictive policy toward the freedom and independence of women in all walks of life eventually won the day in this field as well, and women were first exempted and then barred from all participation in Jewish learning (see, in particular BT Kiddushin 30a). This meant, of course, that throughout Jewish history Jewish women produced very little written evidence and have, for the most part, remained mute to us.

The above attempt to present an overall view of women’s position in Judaism in the post-biblical period has placed much emphasis on women as Jews. However, in most respects Judaism was no different from the cultures in which it thrived (first the Semitic east and then the Greco-Roman west). Its attitude to women was, with slight nuances, no different. Judaism was principally a patriarchal, androcentric society, which viewed women as second-class citizens and as property belonging to various male members of the family.

Boyarin, Daniel. Carnal

Israel: Reading Sex in Talmudic Culture. Berkeley: 1993.

This book discusses rabbinic attitudes to sex, using the methodology of intertextually.

The book is sympathetic both to rabbinic Judaism and the feminist cause and

suggests many very attractive readings of rabbinic sources.

Brooten, Bernadette. Women

Leaders in the Ancient Synagogue. Atlanta: 1982.

This groundbreaking historical study of Jewish inscriptions mentioning women

in leadership positions, is of major importance to a feminist reading of historical

material, and offers enlightening critique of pre-feminist readings of the

same texts.

Cotton, Hannah M. “A Canceled Marriage Contract from the Judaean Desert (XHev/Se

GR. 2).” Journal

of Roman Studies 84 (1994): 64–86.

This article makes the important distinction between bride-price and dowry

in Jewish documentary papyri.

Fonfobert, Charlotte Elisheva. Menstrual

Purity: Rabbinic and Christian Reconstructions of Biblical Gender.

Stanford: 2000.

This study offers an inspired post-modern reading of many rabbinic texts that

deal with menstruation.

Halpern-Amaru, Betsy. The

Empowerment of Women in the Book of Jubilees. Leiden: 1999.

This study is an attempt to elucidate a system according to which the Book

of Jubilees, a second century B.C.E.

sectarian Jewish composition, contains the issue of women in the biblical

Book of Genesis.

Hauptman, Judith. Rereading

the Rabbis: A Woman’s Voice. Boulder CO: 1997.

This book offers a consciously feminist reading of most of the major rabbinic

texts dealing with women’s position within Judaism.

Hauptman, Judith. “Mishnah Gittin as a Pietist Document” (Hebrew). Proceedings of the Tenth World Congress of Jewish Studies C/1 (Jerusalem 1990): 23–30.

——. “Maternal Dissent: Women and Procreation in the Mishnah.” Tikkun 6/6 (1991): 80–1; 94–5.

——. “Women’s Voluntary Performance of Commandments from which They are Exempt.”

(Hebrew) Proceedings

of the Eleventh World Congress of Jewish Studies C/1 (Jerusalem 1994):

161–168.

These articles are a representative sample of Hauptman’s project, in which

she offers a view into the “roads not taken” by the rabbis, when formulating

their legal decisions about women. This she does mainly by comparing parallel

traditions about women in the Mishnah

and the Tosefta,

and showing that the Mishnah usually ruled in a more conservative manner.

Ilan, Tal. Jewish

Women in Greco-Roman Palestine. Tübingen: 1995.

This book is an attempt to place Jewish sources of late antiquity, mentioning

women, into a historical context.

Ilan, Tal. Mine

and Yours are Hers. Leiden: 1997.

This book is an attempt to formulate a methodology with which to approach

rabbinic literature as a source for Jewish women’s history. It uses the rabbinic

presentation of Rabbi Akiva’s wife as a paradigm that demonstrates the various

approaches explored in the book.

Ilan, Tal. Integrating

Women into Second Temple History. Tübingen: 1999.

This book is a collection of articles that address some of the political issues

that involved women in late antiquity Judaism. It discusses women’s sectarianism,

leadership and image in major historical works as well as the use of archaeological

finds in the study of women’s position.

Kraemer, Ross S. “Monastic Jewish Women in Greco-Roman Egypt: Philo on the

Therapeutrides.” Signs:

Journal of Women in Culture and Society 14 (1989): 342–70.

This article is the most updated discussion of women’s participation in the

Jewish sect of the Therapeutai in Egypt.

Levine, Amy-Jill, ed. “Women

Like This”: New Perspectives on Jewish Women in The Greco-Roman World.

Atlanta: 1991.

This excellent collection of articles contains discussions of women’s roles

in most of the major Jewish writings of the Second Temple period—Judith, Susanna,

Pseudo-Philo, Joseph and Asenath, the Books of the Maccabees, even the New

Testament.

Neusner, Jacob. A

History of the Mishnaic Law of Women, vol. 5. Leiden: 1988.

This is Neusner’s formative introduction to the Order of Women in the Mishnah,

where he formulated his views about the purpose and setting of this work,

and placed it within the wider context of the other five orders.

Peskowitz, Miriam. Spinning

Fantasies: Rabbis, Gender and History. Berkeley: 1997.

This is a very suggestive study on the relationship between gender, work and

imagery as found in rabbinic literature. It is primarily interested in demonstrating

how textile work was viewed as gender specific, and how well this view promoted

by rabbinic literature fits into the wider Greco-Roman world of the rabbis.

Satlow, Michael. Tasting

the Dish: Rabbinic Rhetorics of Sexuality. Atlanta: 1995.

This study is an attempt to systematize rabbinic rhetoric about sexuality.

It is a very thorough and comprehensive study.

Schuller, Eileen. “Women in the Dead Sea Scrolls.” In Methods

of Investigation of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Khirbet of Qumran Site: Present

Realities and Future Prospects. Edited by M. O. Wise, N. Golb, J. J.

Collins and D. G. Pardee. Annals

of the New York Academy of Science 722; New York: 1993, 115–131.

This is, to date, the best discussion of the debated issue of women’s membership

in the Dead Sea Sect. The question is especially potent because it impinges

on the identification of the Dead Sea Sect with Essenes, who, according to

Josephus, were celibate.

Schüssler-Fiorenza, Elisabeth. In

Memory of Her: A Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Beginnings.

New York: 1982, 88–120.

This is an early but still excellent reconstruction of women’s membership

in the Jesus movement, its social background and ideological appeal to them.

Sly, Dorothy. Philo’s

Perceptions of Women. Atlanta: 1990.

This study examines Philo, the Alexandrian Jewish philosopher’s use of gendered

categories and language in order to elucidate his sympathies and antipathies

toward women. It shows in a systematic way Philo’s biased, negative approach

to woman as a philosophical concept, probably hinting also to his attitude

to real women.

Trenchard, Charles W. Ben

Sira’s View on Women: A Literary Analysis. Chico, CA: 1982.

This is a careful linguistic study of all the passages in Ben Sira that deal

with women and the feminine. Although Trenchard is only prepared to pronounce

very limited conclusions with regard to his finding, his close literary reading

is most useful, and his study could be used to reach far broader conclusions.

Wegner, Judith Romney. Chattel

or Person?: The Status of Women in the Mishnah.

Oxford: 1988.

This is a thorough, systematic study of the way women are viewed in the Mishnah.

It attempts to build an all-embracing model of the Mishnah’s attitude to women.

It shows that the Mishnah distinguishes clearly between women who are independent

and woman who are under a man’s tutelage. The former are accorded a status

that is equal to men. The latter are treated as chattel.