Printers

Jewish women have been involved in the production of Hebrew books from the earliest days of Hebrew printing in the fifteenth century. Until the nineteenth century, printing was a cottage industry, with an entire family joining in helping with the multiple tasks involved. Both Jewish and non-Jewish widows mainly took over the printing press after their husbands died; some remarried and their new husbands took over the business, but many widows continued operating the businesses themselves. Women printers played important roles in both the Sephardi and the Ashkenazi worlds. Among the many women printers in Eastern Europe, perhaps the most interesting phenomenon is the preponderance of Jewish women involving in printing in the city of Lemberg (Lvov) in the nineteenth century.

Jewish Women Printing Pioneers

Jewish women have been involved in the production of Hebrew books from the earliest days of Hebrew printing. In the 1470s, the colophon of a Hebrew book Behinat Olam printed in the Italian city of Mantua declared, “I, Estellina, the wife of my worthy husband Abraham Conat, wrote this book Behinat Olam with the aid of Jacob Levi of Tarascon.” It is well known that the author of the book, an ethical work written in Hebrew in the first half of the fourteenth century, was Jedaiah Ben Abraham Bedersi (c. 1270–1340). But it was Estellina who arranged for its printing in Mantua and was actually involved in the process. She used the word “wrote” because there was as yet no term in Hebrew for “printing.” According to her husband, who was the proprietor of the press, Estellina “wrote” the book “with many pens, without the aid of a miracle.”

Unfortunately, little is known about Estellina. Indeed, of the eight books printed by the Conats, only one, a volume of the Tur (the popular legal code by Jacob ben Asher, that served as the precursor of Joseph Caro’s Shulchan Aruch), bears a date (according to its colophon, its printing was completed on June 6, 1476). Scholars are convinced that Bechinat Olam was one of the first Mantua books printed and that its printing dates from the second half of 1473 or the beginning of 1474. Estellina’s name is not mentioned in any of the other volumes printed by her husband, and we do not know when she died. Because there is so little information about the Conats and their lives, it is possible that she introduced her husband, a physician, to the craft of printing, which he then continued after her death. We certainly know from her colophon that Estellina Conat printed before Anna Rugerin of Augsburg, considered the first female typographer to inscribe her name in a colophon, in 1484, and even before the nuns in the convent of San Jacopo di Ripoli typeset for the Ripoli press, which issued about 100 different titles between 1476 and 1484.

Scholars have also debated the role of Meshullam Cusi’s widow in the printing of the second dated Hebrew book, the four volumes of the Tur, printed in Piove di Sacco, Italy, near Venice, in 1475. Some scholars have argued that Cusi’s wife was named Devora, that she printed Hoshen Mishpat after the death of her husband and sons, and that she wrote the colophon in that volume of the Tur using quotations from the biblical story of Devora in the book of Judges because that was indeed her name. But this theory is not accepted by most scholars, who consider that the name and quotations from the biblical story of Devora are only metaphorical. Nevertheless, the fact that scholars have seriously raised the possibility that part of the second dated Hebrew book was printed by a named woman is exciting and makes the role of Estellina Conat particularly important.

In general, until the nineteenth century, printing was a cottage industry; adjoining living and printing areas enabled an entire family to join in helping with the multiple tasks involved. Both Jewish and non-Jewish widows mainly took over the printing press after their husbands died. Since some widows married soon after, their new husbands, often also printers, took over the business. Many widows, however, chose to continue operating the businesses themselves in order to support their families, and sometimes to pass them on to their children.

After Estellina Conat, the names of at least 54 other Jewish women printers appeared on colophons or title-pages up to the 1920s, with many more since then. It is hard to estimate numbers because so many Hebrew books were lost and destroyed during periods of persecution and expulsion over the centuries. Some of the women are mentioned specifically by name; in other cases, lines in the colophons and title pages state, as in the case of the famous Proops family of Amsterdam, “Printed by the Widow and Orphans of Jacob (or Joseph) Proops,” or “Printed by the Widow and Brothers Romm” in late nineteenth-century Vilna. Countless Jewish women likely contributed anonymously to the printing endeavor throughout the centuries.

Women Printers in the Sephardi World

Evidence exists from external sources of some female printers whose books have not survived. A converso, Juan de Lucena, is considered the first Hebrew printer in the Iberian peninsula, even though no books survive from his press. Records of the Spanish Inquisition state that he and four of his daughters were accused of printing Hebrew books in the village of Montalban and in Toledo before 1480. In 1485, one of his daughters confessed before the Inquisition that she had helped her father print Hebrew books: “I accuse myself of having been delinquent by helping my father to write in Hebrew with type, which sin I have committed while a girl in my father’s house.” Almost 50 years later, another daughter was condemned to life imprisonment after a similar confession.

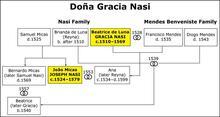

There is no evidence of women being involved in Hebrew printing in most lands of the Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardic diaspora, even though there were important Hebrew printing centers in Salonika, Fez, Izmir, and Adrianople. There was one spectacular exception: Doña Reyna Mendes (c. 1539–1599) in Constantinople. She was the daughter of Doña Gracia Nasi Mendes, the famous businesswoman and philanthropist who came to Constantinople in 1553, and the wife of Joseph Nasi (1524–1579), advisor to the Sultan and one of the most important men in the Ottoman Empire. Her mother had supported many scholars and underwritten the printing of Jewish books, but Doña Reyna was the first Jewish woman to establish and maintain a press herself, rather than inheriting one from her husband. When Doña Reyna’s husband died, the authorities confiscated almost all of his wealth. With the remainder she established a press in Belvedere, near Constantinople, and later another press in the Constantinople suburb of Kuru Cesme. She published at least fifteen books, including prayer books and a tractate of the Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud. A typical title page of her printing press declared: “Printed in the house and with the type of the noble lady of noble lineage Reyna (may she be blessed among women), widow of the Duke, Prince and Noble in Israel, Don Joseph Nasi of blessed memory … near Constantinople, the great city, which is under the rule of the great and mighty Sultan Mohammed.” At the time, hers was the only printing press in Constantinople in any language, and thus she had no community of printers or patrons for support. After Doña Reyna’s death in 1599, the press stopped functioning and no further Hebrew books were printed until 1638. The first Turkish book was printed in the city only in 1729.

Women Printers in the Ashkenazi World

Famous in the annals of the contribution of Jewish women to printing were two typesetters, Ella and Gela, at the end of the seventeenth century—daughters of a convert to Judaism named Moses who first worked as a printer and then had his own printing house in various cities, including Amsterdam, Dessau, Berlin, Frankfurt an der Oder, and Halle. Ella set type in her father’s printing house in Dessau. In 1696, the Yiddish rhymed colophon to a volume stated: “These Yiddish letters I set with my own hand, Ella, daughter of Moses of Holland. My years number no more than nine, the only girl of six children. If you find an error, please remember that it was set by a child.” Ella moved to Frankfurt an der Oder and worked with her brother on the important Talmud edition printed there between 1697 and 1699; this she noted at the end of Tractate Niddah. Her younger sister Gela set the type for two books in her father’s press in Halle between 1709 and 1710. In a prayer book printed in 1710, Gela wrote:

Of this beautiful prayer book from beginning to end,

I set all the letters in type with my own hands.

I, Gela the daughter of Moses the printer, whose mother was Friede. …

She bore me among ten children. I am a maiden still under twelve years.

Among the many women printers in Eastern Europe, perhaps the most interesting phenomenon is the preponderance of Jewish women involved in the printing profession in the city of Lemberg (Lvov) in the nineteenth century. Until 1782, when the Austrian authorities ordered the Hebrew printers of Zolkiev, a small city near Lemberg, to move to Lemberg to facilitate censorship, Lemberg had no Hebrew printing, but it quickly became a printing center for Jewish books, which were then distributed throughout Eastern Europe and the Balkans. (The city known by many names, due to wars and occupations, through its long history: Leopolis, Lvov, Lwow, and Lemberg, and is now known as Lviv, a major city in the independent nation of Ukraine).

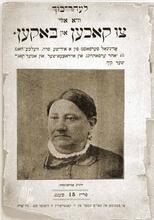

One of the printers in Zolkiev was Judith Rosanes, a great-granddaughter of Uri Phoebus, the printer who had come to Zolkiev in 1691 from Amsterdam. She printed by herself in Zolkiev, with her husband David Mann before his death, and also with various of her cousins who were also printers. In 1782 she moved to Lemberg and established her printing business there. She then married Rabbi Hirsch Rosanes, rabbi of the city and a great scholar. Altogether Judith Rosanes printed at least 50 books before her death in 1805. She was the first Jewish woman to print Hebrew books on a commercial basis over an extended period—for at least 25 years. It is known that she had 24 employees (all male). She was probably helped in part by her son from her first marriage, Naftali Hertz Grossman, but he set up his own printing press in Lemberg in 1797. The name of Judith Rosanes was so famous as a printer of Hebrew texts that in the middle of the nineteenth century, when the authorities forbade the publication of Hasidic books, printers used her name to suggest that the books had been printed much earlier.

The wives of two of Judith Rosanes’s cousins also printed in Lemberg after the death of their husbands: Chaya Taube, wife of the printer Aharon Madpis, and Tsharni Letteris, wife of Ze’ev Wolf Letteris. The former ran a press by herself under her own name for about 33 years until she handed it over to her son. The latter received official permission to return to Zolkiev in 1793 and published there for at least nineteen years. The daughter-in-law and granddaughter of Judith Rosanes also ran a printing press in Lemberg. When Naftali Hertz Grossman died in 1827, his wife Chave Grossman continued running the press until 1849. When she died, the printing press passed to her daughter Feige, who printed at the press until at least 1857. It has been suggested that the printed books falsely attributed to Judith Rosanes to avoid government prohibitions on printing were actually printed by Chave Grossman, her daughter-in-law. In any case, it is exciting to have three generations of females from the same family involved in Lemberg printing: first Judith Rosanes, then her daughter in law Chave Grossman, and last her granddaughter Feige Grossman.

The most famous Jewish woman printer in Lemberg in the second half of the nineteenth century was Pesel Balaban. She was already very active in the business, founded originally by her father-in-law, while her husband Pinhus Moshe was alive, but after his death she expanded the press, producing high-quality editions of halakhic texts such as the Shulhan Arukh (Code of Jewish Law).

At the end of the nineteenth century the most famous Jewish printing house was that of the Widow and brothers Romm in Vilna. The Romm family began printing in 1799 and continued until 1940. However, it was under the management of Devorah Romm (d. 1903) that it had its greatest success. In 1860, the death of her husband left her, his second wife, aged twenty-nine, with six children and one from his previous marriage. She took over the firm and expanded it in partnership with her two brothers-in-law until her death. She was the dynamic and hard-working partner; helped at first by her father. She was the major decision-maker in the firm as it produced thousands of volumes in superior editions. She personally hired the enterprising literary director Samuel Shraga Feigensohn. The Romm edition of the Babylonian Talmud in the 1880s, incorporating textual variants from rare manuscripts in different libraries, was a landmark in Hebrew printing; 22,000 copies of the first volume were sold by advance subscription, and this edition became a model for all later editions. The press also printed much Haskalah (Enlightenment) literature. After Devorah’s death, the Romm press declined and was sold in 1910.

Akrap, Domagoj. “Frauen im judischen Buchwesen.” In Beste aller Frauen: weibliche Dimensionen im Judentum, edited by Gabriele Kohlbauer-Fritz and Wiebke Krohn, 134-143. Vienna: Jüdisches Museum Wien, 2007. [German]

Breger, Jennifer. “The Role of Jewish Women in Hebrew Printing.” Antiquarian Bookman (March 29, 1993): 1320–1329.

Breger, Jennifer. “Printing, Hebrew: Women Printers.” Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd ed. Vol. 16, p. 540, cf. vol 22 pp. 752-753. Detroit, MI: 2007.

Elior, Rachel. “Nashim ma’atikot, nashim madpisot ve-nashim melumadot.” In Savta lo yad’ah ke’ro u-khetov (Grandmother Did Not Know How to Read and Write). Jerusalem: 2018, 687-705. [Hebrew]

Feffer, Solomon. “Of Ladies and Converts and Tomes: An Essay in Hebrew Booklore.” In Essays on Jewish Booklore, edited by Philip Goodman, 365–378. New York: KTAV Publishing House, 1972.

Fraenkel, Sara. “Who was the Falsificator of Judith Rozanis in Lemberg?” Proceedings of the Ninth World Congress of Jewish Studies, Division D, Vol. 1. Jerusalem: 1985, 175–182. [Hebrew]

Genauer, Eli. “‘I Have Also Engaged in This Work of Heaven’ : The Vital Contribution of Women to Hebrew Printing.” Jewish Action, Winter 2016.

Haberman, A. M. Jewish Women as Printers, Typesetters, Publishers and Book Patrons. Berlin: 1933. [Hebrew]‘

Iakerson, Shimon. Katalog ha-inkunabulim ha-’ivriyim me-osef sifriyat Bet ha Midrash le-Rabanim be- Amerika=Catalogue of Hebrew Incunabula from the Collection of the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 2004-2005. 2 vols.

Karp, Abraham. “Let Her Works Praise Her.” In From the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress. Washington D.C.: Library of Congress, 1991, 167–171.

Nissim, Daniele. “Gli ebrei a Piove di Sacco e la prima tipografiia ebraica.” Rassegno mensile di Israel 38 (1972): 1-12. [Italian]

Offenberg, Adri K. “The Chronology of Hebrew Printing at Mantua in the Fifteenth Century: A Re’examination.” The Library 6th series 16 (1994): 298-315.

Steinschneider,Moritz. “Die juduschen Frauen und die judische Literatur, I : Druckerinnen und Setzerinnen.“ Hebraische Bibliographie I (1858) pp 66-68 and 2 (1859) pp 33-35. [German]

Yaari, Avraham. “Women in the Holy Endeavor (of Printing).” In Mehkerei Sefer. Jerusalem: 1958, 256–302. [Hebrew]

Yaari, Avraham. “The Printing House of Rabbanit Judith Rosanes in Lvov.” Kiryat Sefer 27 (1940): Miscellaneous Bibliographical Note 36, 95–108. [Hebrew]