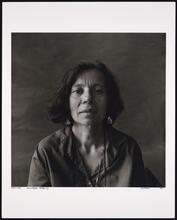

Adrienne Cecile Rich

Born in Baltimore in 1929 to a Protestant mother and a Jewish father, Adrienne Rich achieved acclaim early on for poems that were praised for qualities like control and elegance. She later moved away from the formal restraint of her early work and towards an aesthetic more in line with her increasingly radical politics. From the early 1960s onwards, Rich insisted on bringing together the personal and the political in poems and essays that explore issues such as motherhood, sexuality, racism, anti-Semitism, and war. Through her work, Rich shows how even the most intimate moments can shed light on pressing political issues, while also revealing how politics inform every aspect of our lives.

Family, Education, and Early Success

Adrienne Cecile Rich was born on May 16, 1929, in Baltimore, Maryland. Her mother, Helen Elizabeth Rich, was a southern Protestant and a composer and pianist by training; her promising musical career came to an end when she married Adrienne’s father, the Alabama-born Arnold Rich, a secular Jewish physician who would help foster a love for books in the young Adrienne and who encouraged her writerly ambitions. Rich’s father was a formidable influence on her life and work and his traditionalist approach informed the poet’s earliest work, though she later rebelled against him, both in her personal life and in her poetry.

Rich first garnered critical acclaim when her first book of poems, A Change of World, was selected by W.H. Auden for the Yale Younger Poets Series in 1951, the same year she graduated cum laude from Radcliffe College. Praise for the book was couched in patronizing language, and its success seemed to be directly tied to a sense of decorum and agreeability exuded by poems that, as Auden put it, were “neatly and modestly dressed, speak quietly but do not mumble, respect their elders but are not cowed by them.” Indeed, Rich’s early work is often described as “formal,” “elegant,” and “controlled,” adjectives that seem utterly at odds with the radical feminist poet whose life’s work would be to dismantle a patriarchal system that accepted women like Rich only so long as they conformed to rigid expectations of feminine comportment.

In 1953, Rich married the Harvard economist Alfred Haskell Conrad, a secular Jew (he had changed his surname from Cohen) who had been raised in a traditional Orthodox household in Brooklyn and through whom Rich began to more connect more deeply with her own Jewish heritage. Within six years, Rich had given birth to three sons. Her second collection of poems, The Diamond Cutters and Other Poems, was published in 1955.

Feminist Awakening

Not until 1963, with the publication of Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law: Poems 1954-1962, did Rich began to make a name for herself as a feminist poet. Indeed, the collection’s title poem was, according to Rich, her “first overtly feminist poem.” As she later recalled, when she showed the manuscript to friends, they urged her to choose a different title. “People will think it’s some sort of female diatribe or complaint,” they told her. But Rich wouldn’t back down: “I wanted that title and I wanted that poem.” Rich’s friends were right in their predictions. Previously laudatory critics censured the book for being “too personal, too bitter.” But the poet had found her voice. As she said in an interview toward the end of her life, “The split in our language between ‘political’ and ‘personal’ has, I think, been a trap” (Waldman). In her poetry and her prose Rich sought to bridge that artificial divide, bringing together the personal and the political to reveal how they are and always have been deeply and inextricably intertwined.

In 1970, Rich separated from her husband of seventeen years. Soon after, he committed suicide, leaving Rich to raise their three adolescent sons alone. In 1976, Rich published Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution, in which she drew on her own experiences as both a daughter and a mother to examine the patriarchal underpinnings of motherhood. Rich argued that motherhood precedes nationalism and tribalism and that “we need to understand the power and powerlessness embodied in motherhood in patriarchal culture.” It was this very culture, according to Rich, that had “created images of the archetypal Mother which reinforce the conservatism of motherhood and convert it to an energy for the renewal of male power.”

Rich was deeply involved in the political struggles of her day. In a 1991 interview she recalled the early days of the Civil Rights movement, when she first “began to hear Black voices describing and analyzing what were the concrete issues for Black people, like segregation, like racism,” which, she said “came. . . as a great relief.” As she went on to explain, “it was like finding language for something that I’d needed a language for all along. That was the first place where I heard a language to name oppression.”

In her 1971 essay “When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Revision,” Rich laid out her feminist vision, or “Re-vision,” which she defined as “the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction,” and which, she wrote, “is for women more than a chapter in cultural history: it is an act of survival.” As Rich explained, “We need to know the writing of the past, and know it differently than we have ever known it; not to pass on a tradition but to break its hold over us.”

In her introduction to Rich’s posthumously published Collected Poems: 1950-2012, Claudia Rankine recalled her early encounters with Rich’s work, including this 1971 essay; she read the essay alongside James Baldwin, and both gave voice, she writes, to “dissatisfaction with systems invested in a single, dominant, oppressive narrative.” These two writers informed Rankine’s own “initial understanding of feminism and racism.”

In 1972, Rich won the National Book Award (along with Allen Ginsberg) for her groundbreaking collection Diving into the Wreck: Poems 1971–1972. She famously declined to accept the award in her own name, sharing it instead with her co-finalists, Alice Walker and Audre Lorde, in the name of all women. Critical reception of this collection reflected the tensions inherent in Rich’s position as a poet whose work was unabashedly, even militantly, feminist. Rich had become a controversial figure, drawing the ire of critics like Helen Vendler, who in Parnassus: Poetry in Review, singled out the poem “Rape” in Diving into the Wreck for particular damnation. “This poem,” she wrote, “like some others [in the book], is a deliberate refusal of the modulations of intelligence in favor of ... propaganda.” As the poet and critic Wayne Koesetnbaum wrote decades later, in his New York Times review of Rich’s Collected Poems, “Curmudgeonly purists criticized her work’s political (lesbian-feminist) core. They ignored the fact that she chose to honor poetry by performing societal inquiries in verse lines that always remembered, in their sinews, the exaltations and laments of such noble elders as John Keats, Langston Hughes and Emily Dickinson.”

Lesbian and Jewish: An Intersectional Identity

Session on "Queer Dreams of Jewish Women's Poetry" for the Jewish Women's Archive's Global Day of Learning, in celebration of the launch of the Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, June 28, 2021. Featuring Zohar Weiman-Kelman in conversation with Judith Rosenbaum.

In the mid-1970s, Rich met the woman who would become her partner and life companion, Jamaican-born novelist Michelle Cliff. The two later co-edited a lesbian-feminist journal entitled Sinister Wisdom. During this time Rich began to publish explicitly lesbian poems, including the cycle “Twenty-One Love Poems,” which appeared in The Dream of a Common Language: Poems 1974-1977. In the cycle’s opening poem, Rich speaks back to a world in which “No one has imagined us,” a pair of lesbian lovers, and insists: “We want to live like trees, / sycamores blazing through the sulfuric air, / dappled with scars, still exuberantly budding, / our animal passion rooted in the city.”

In her essay “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence,” published in 1980, Rich argued that heterosexuality is a “political institution” whose aim is to assure “male right of physical, economic and emotional access” to women. According to Rich, “lesbian existence,” by which she meant “both the fact of the historical presence of lesbians and our continuing creation of the meaning of that existence,” presented a fundamental challenge to the “male right of access to women.” In this essay Rich coined the term “lesbian continuum” to refer to “a range—through each woman’s life and throughout history—of woman-identified experience,” which includes but is not limited to erotic and romantic love. The essay first appeared in print in 1978 in the feminist academic journal Signs and was later included a collection of essays, Blood, Bread and Poetry: Selected Prose 1979–1986.

Among other notable essays in that same collection was Rich’s “Split at the Root: An Essay on Jewish Identity,” in which Rich examines her fraught relationship with her Jewish father, a man who kept his own Jewish identity under wraps. In addition, Rich considers “the sources and the flickering presence of my own ambivalence as a Jew; the daily mundane anti-Semitisms of my entire life.” Originally written for Nice Jewish Girls: A Lesbian Anthology, edited by Evelyn Torton Beck, Rich’s essay also functions as a kind of companion piece to “Sources,” a long poem written during the same period, in which the poet addresses the two Jewish men in her life: her father and her husband. In section seventeen, Rich levels with her father as she speaks of the Jew “you most feared, the one from the (Yiddish) Small-town Jewish community in Eastern Europe.shtetl, from Brooklyn, from the wrong part of history, the wrong accent, the wrong class. The one I left you for. The one both like and unlike you, who explained you to me for years, who could not explain himself.” Addressing her late husband in section 22, Rich gives voice to an aching desire “to speak to you now. To say: no person, trying to take responsibility for her or his identity, should have to be so alone.”

As Maeera Shreiber has argued, the “link between feminism and Judaism” was particularly fraught for Rich, since her Jewish identity involved “retaining a relation to paternal authority.” At the same time, as Shreiber shows, through the “refiguring of the father” in this poem, from “the face of patriarchy” to someone repressing within “the suffering of the Jew,” Rich taps into the “culturally entrenched image of the Jew as the feminized other.”

Questions of identity are also at the center of “Yom Kippur 1984,” which opens with these lines: “What is a Jew in solitude? / What would it mean not to feel lonely or afraid / far from your own or those you have called your own?” This poem, which, like “Sources,” appeared in the 1986 collection Your Native Land, Your Life, asks how the individual is constituted both in relation to and apart from community.

Though it would be several more years before Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality, Rich’s politics was already being shaped by an intersectional approach, something that is evident in “Yom Kippur 1984,” which speaks to a range of marginalized identities and how they intersect. So, too, “Split at the Root,” which focuses in particular on the the intersections of race and class and how they inflect Jewish social identity. According to Rich, American Jewish identity was itself split in two, between “the Jew as radical visionary and activist who understands oppression firsthand, and the Jew as part of America’s devouring plan in which the persecuted, called to assimilation, learn that the price is to engage in persecution.”

In 1990, Rich became editor of the newly founded Bridges: A Journal for Jewish Feminists and Our Friends, published by the New Jewish Agenda. Rich continued to explore Jewish themes in An Atlas of the Difficult World: Poems 1988–1991. Writing about Rich’s turn to the ancient genre of lament in this collection, Shreiber shows how the poet “lays claim to the form as a woman and as a Jew.” The title poem of this work focuses on American national identity during the Gulf War. In this poem, as Piotr Gwiazda suggests, Rich projects “a new audience for American poetry,” which itself “forms a metaphor for the rapidly transforming American society—multi-voiced, multicolored, multicultural, constantly in the process of self-definition."

Interspersed among the poems of The School Among the Ruins (2004) are references to Israel and Judaism. In one poem, Rich “interviews” an Israeli soldier who regrets some of the orders he carried out; in another, she questions what we are carrying with us into the twenty-first century and answers: “Sacks of laundry/of books… Pet iguanas/oxygen tanks/The tablets of Moses.”

University Affiliations and Awards

Rich taught at various colleges and universities throughout her life, beginning as a lecturer at Swarthmore College in 1967 and continuing through the Graduate School of the Arts of Columbia University and on to City College of the City University of New York. In 1972, she left New York to teach at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts. Among the other institutions where Rich carried on her work as both poet and teacher are Bryn Mawr, Rutgers, Cornell, Scripps, and Pacific Oaks. From 1986 to 1993 Rich was professor of English and feminist studies at Stanford University. She was elected a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets in 1999, having received the Academy’s Tanning Award for Mastery in the Art of Poetry (the Wallace Stevens Award) in 1996.

In addition to the National Book Award, Rich was a recipient of the first Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize (1986), the Common Wealth Award in Literature (1991), the National Poetry Association Award for Distinguished Service to the Art of Poetry (1989), the Frost Silver Medal for lifetime achievement (1992), a MacArthur Fellowship (1994), the Lannan Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award (1999), and the Bollingen Prize for Poetry (2003).

In 1997, Rich publicly refused to accept the National Medal of Arts, the United States government’s foremost award in the arts. In a letter published by the New York Times, Rich wrote to Jane Alexander, then-head of the National Endowment for the Arts: “I cannot accept such an award from President Clinton or this White House because the very meaning of art, as I understand it, is incompatible with the cynical politics of this administration.” In a further letter to Alexander, she explained:

Art—in my own case the art of poetry—means nothing if it simply decorates the dinner table of power which holds it hostage. The radical disparities of wealth and power in America are widening at a devastating rate. A President cannot meaningfully honor certain token artists while the people at large are so dishonored… My concern for my country is inextricable from my concerns as an artist. I could not participate in a ritual which would feel so hypocritical to me.

Late Work and Death

Upon reading Rich’s Midnight Salvage (1999), former U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Hass wrote that what “distinguishes her art is a restless need to confront difficulty, a refusal to be easily appeased.”

Though she never gave up, Rich did express despair in some of her later poems. In the title poem of Tonight No Poetry Will Serve, the last collection published in her lifetime, Rich points to a world in which “no poetry / will serve.” As she later explained in an interview, this poem, written in 2007, “was inflected. . . by interviews . . . about Guantánamo, waterboarding, official U.S. denials of torture, the ‘renditioning’ of presumed terrorists to countries where they would inevitably be tortured. The line ‘Tonight I think no poetry will serve’ suggests that no poetry can serve to mitigate such acts, they nullify language itself.”

Rich died on March 27, 2012, at her home in Santa Cruz, California, from complications of rheumatoid arthritis, a disease from which she had suffered for much of her adult life. In addition to her partner, three sons, and grandchildren, she left behind generations of women—and men—inspired to continue the work she had begun in pursuit of a more just and equitable world for all.

In one of her final poems, “Endpapers,” Rich writes: “The signature to a life requires / the search for a method / rejection of posturing / trust in the witnesses / a vial of invisible ink / a sheet of paper held steady / after the end-stroke / above a deciphering flame.”

Selected Works

Collected Poems: 1950-2012. New York: W.W. Norton, 2016.

Tonight No Poetry Will Serve: Poems 2007-2010. New York: W.W. Norton, 2011.

The School Among the Ruins: Poems 2000–2004. New York: W.W. Norton, 2004.

Editor of Muriel Rukeyser Selected Poems. New York: Library of America, 2004.

What is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics. New York: W.W. Norton, 2003.

Arts of the Possible: Essays and Conversations. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

Fox: Poems 1998-2000. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

The Facts of a Doorframe: Poems 1951-2001. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

Midnight Salvage: Poems 1995-1998. New York: W.W. Norton, 1999.

“Why I Refused the National Medal of the Arts.” Los Angeles Times Book Section (August 3, 1997).

Dark Fields of the Republic: Poems 1991–1995. New York: W.W. Norton, 1995.

What Is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics. New York: W.W. Norton, 1994.

An Atlas of the Difficult World: Poems 1988–1991. New York: W.W. Norton, 1991.

Blood, Bread and Poetry: Selected Prose 1979–1986. New York: W.W. Norton, 1986.

Your Native Land, Your Life. New York: W.W. Norton, 1986.

A Wild Patience Has Taken Me This Far: Poems 1978–1981. New York: W.W. Norton, 1981.

“Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence” (1980).

On Lies, Secrets and Silence: Selected Prose 1966–1978. New York: W.W. Norton, 1979.

The Dream of a Common Language: Poems 1974–1977. New York: W.W. Norton, 1978.

Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution. New York: W.W. Norton, 1976.

Diving into the Wreck: Poems 1971–1972. New York: W.W. Norton, 1973.

Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law: Poems 1954–1962. New York: Harper and Row, 1963.

The Diamond Cutters and Other Poems. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1955.

A Change of World. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1951.

“Adrienne Cecile Rich.” In Her Heritage: A Biographical Encyclopedia of Famous American Women. Pilgrim New Media, 1994.

Contemporary Authors, New Revision Series. Vol. 20.

Erickson, Peter. “Singing America: From Walt Whitman to Adrienne Rich.” Kenyon Review, January 1, 1995.

Gelpi, Barbara Charlesworth, Albert Gelpi, and Brett Millier. Adrienne Rich’s Poetry and Prose. Norton Critical Edition, 2nd ed. New York: W. W. Norton, 2018.

Gwiazda, Piotr. “’Nothing Else Left to Read’: Poetry and Audience in Adrienne Rich’s ‘An Atlas of the Difficult World.’” Journal of Modern Literature 28, no. 2 (Winter, 2005): 165-188. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3831720.

Hass, Robert. “Poet’s Choice.” Washington Post Book World, May 16, 1999.

Koestenbaum, Wayne. “Adrienne Rich’s Poetry Became Political, but it Remained Rooted in Material Fact.” New York Times, July 15, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/17/books/review/adrienne-rich-collected-poems-1950-2012.html

Rankine, Claudia. Introduction to Collected Poems: 1950-2012 by Adrienne Rich. New York: W.W. Norton, 2016.

Rothschild, Matthew. “Adrienne Rich.” Progressive, January 1, 1994.

Shreiber, Maeera. “Adrienne Rich, Women’s Mourning and the Limits of Lament.” In Dwelling in Possibility: Women Poets and Critics on Poetry, eds. Yopie Prins and Maeera Shreiber. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997.

Waldman, Kate. “Adrienne Rich on ‘Tonight No Poetry Will Serve.’” The Paris Review, March 2, 2011. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2011/03/02/adrienne-rich-on-%E2%80%98tonight-no-poetry-will-serve%E2%80%99/