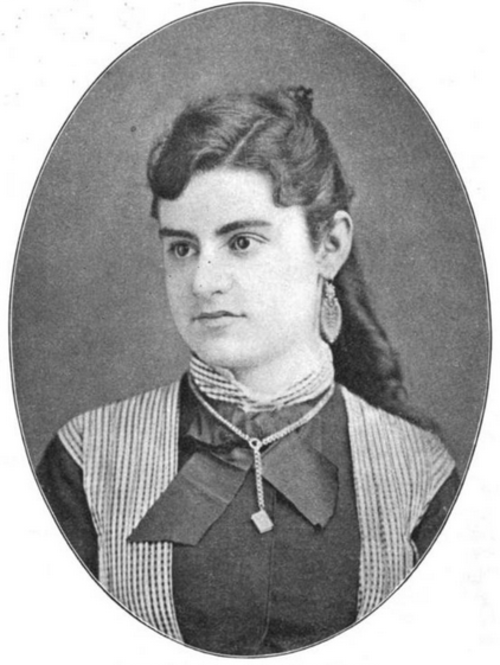

Julia Richman

A polarizing and important social reformer, Julia Richman sought to better manage the massive influx of immigrants in New York by Americanizing the new arrivals as quickly as possible. Richman helped organize the Young Women’s Hebrew Association and was active in the Educational Alliance, formed in 1885 by American Jews to handle the wave of new immigrants. Richman used both public schools and the Education Alliance to develop a program to train immigrant children in English, penalizing them for speaking their native languages. In 1903 she was named district superintendent of the Lower East Side schools, creating playgrounds, improving school lunches, and enforcing health examinations for students. She also published articles on education and social reform as well as two textbooks, Good Citizenship (1908) and The Pupil’s Arithmetic (1909).

When Julia Richman was eleven years old, she told her family, “I am not pretty...and I am not going to marry, but before I die, all New York will know my name!” When she died, her “promises” had come to pass: She did not marry, and a great many New Yorkers knew her name.

Early Life & Education

Born on October 12, 1855, Julia Richman was the third child of Moses and Theresa (Melis) Richman, German-speaking Jewish immigrants from Prague, Bohemia. Her middle-class family lived first in the Chelsea section of Manhattan, then moved to “Kleindeutschland,” a heavily German district later known as the Lower East Side, and finally settled on Central Park West.

Richman was an excellent student who enjoyed school and wanted to continue her education beyond the eighth grade, but her parents did not see any need for her to do so. A family battle ensued, which Richman won, permitting her to enroll at the newly organized Female Normal College, later renamed Hunter College. At age seventeen, she graduated and began a forty-year career in the New York City schools as a teacher at Public School 59.

Teaching & Early Charitable Work

In addition to her work at the public school, Richman began to teach in the Sabbath school of the Reform Temple Ahawath Chesed, where she and her family were members. This connection led to her involvement in another aspect of Jewish communal life, charitable work. Together with a few other middle-class German Jewish women, she organized the Young Ladies Charitable Union, which after five years was absorbed into the Hebrew Free School Association, of which Richman became a trustee.

As was her wont, Richman worked hard for the association, primarily as a fund-raiser, but she also found time to organize another group, the Young Women’s Hebrew Association, which began as an adjunct of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association. In 1885, when the influx of Eastern European Jews pouring into the Lower East Side caused considerable alarm in the established German Jewish community, several of the groups in which Richman was active joined together to form the Educational Alliance, which became the most important organization of uptown Jews working to Americanize their newly arrived downtown brethren.

Teaching Immigrant Children

In accord with the majority of people concerned with the arrival of thousands of foreigners during the late nineteenth century, Julia Richman saw great danger for the United States if the newcomers did not learn the English language and American ways. Fearing balkanization and fragmentation, she argued that the school must “wrest” immigrant children from the language and customs of their homeland. Her work at the Educational Alliance was one road to this end. In addition to holding English as a second language classes, the alliance offered instruction in American sports, cooking, dressing, and other activities.

Julia Richman, who by 1884 had become the first Jew and first Normal College graduate to be named a grammar school principal, advocated all such efforts. First at the alliance and then in the public schools attended by immigrant children, she developed a language program under which foreign-born children would be tested for knowledge of English and then placed in an appropriate class in which they could remain for six to eight months. During this period, they would be immersed in English, forbidden to use their first language even when at play or in the washrooms. If they disobeyed, their mouths would be washed out with soap (kosher, if appropriate).

Superintendent of Lower East Side Schools

Learning the language of America came first, but Julia Richman wanted the schools to do much more. On her list were the establishment of kindergartens; cheap, nutritious lunches; playgrounds; health examinations; instruction in domestic science for girls and manual training for boys. She was not alone in advocating these initiatives, but when she was elevated to district superintendent of the Lower East Side schools in 1903, she was in a better position than most to put them into effect.

Richman saw her assignment as multifaceted. In her view, the bursting classes, dilapidated buildings, and high dropout rate in her district were only part of a dismal picture. If immigrant children were to become good American citizens, she believed that conditions in the teeming streets surrounding her schools must also be addressed. Settlement house workers, with whom she worked closely, had managed to convince the city to level and erect a fence around a plot of land near Allen Street and thus create a much-needed oasis, but the space was neglected and unsupervised and, as a result, soon became as much of a slum as the blocks around it. Julia Richman, using the clout of her fellow Educational Alliance trustees, forced the Parks Department to live up to its responsibilities. Many residents of the Lower East Side appreciated her efforts on their behalf, but there were also others who resented her “lady bountiful approach” and her public opposition to some East Side institutions, such as street peddling.

Writing & Legacy

Considering the weight of her other activities, it is surprising that Julia Richman was also an author. In addition to her many articles in social service publications such as Outlook, she coauthored The Pupil’s Arithmetic (1909) and Good Citizenship (1908). The first is a text for elementary school teachers, the second for use in civics classes. Other articles presented new educational ideas such as homogeneous grouping and continuous promotion. She also wrote books for Sabbath school teachers, laying out model lessons even an untrained volunteer could follow.

During this same period, Julia Richman raised enough money from her wealthy German Jewish associates, such as Felix Warburg, to establish a settlement, Teachers’ House, which, among other activities, dispatched “visitors” to the homes of truant children and used other methods, including stipends, to enable them to return to school. A placement counselor was also installed at Teachers’ House, responsible for finding jobs for those youngsters who could not be induced to return to the classroom.

In many ways, Julia Richman was a liberated woman while conforming to the rules established by the society in which she lived. Because teaching young children and caring for the unfortunate were permissible female activities, these were the arenas in which she performed. On the other hand, she would not settle for being just an ordinary teacher or charity volunteer. That would not have satisfied her ambition and desire for fame. Within the parameters of acceptable female behavior, she struggled to achieve the power and prominence denied to all but a handful of women of her day.

Julia Richman died in Paris on June 24, 1912.

AJHQ 70:35–51.

AJYB 6 (1904–1905): 169, 14 (1912–1913): 128.

Altman, Addie R., and Bertha R. Proskauer. Julia Richman: An Appreciation of a Great Educator. New York: The Julia Richman High School Association, 1916.

Berrol, Selma. Julia Richman: A Notable Woman. Balch Institute for Ethnic Studies, 1993.

JE.

NAW.

Obituary. NYTimes, June 26, 1912, 13:5.

UJE.