Ruth Schloss

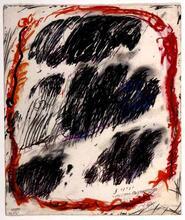

Ruth Schloss’s paintings and drawings expressed her humanistic and moral views and her socio-political commitment. Her works depicted people in her immediate vicinity, events, and landscapes from the first years of the Israeli state during the 1940s onwards. Her gaze was drawn to those who were powerless, marginalized, and ignored. She protested against wars and occupation and demanded social justice for the underprivileged (such as newcomers Mizrahi Jews, Palestinian refugees, and the elderly). Usually, in her works, it was the feminine figure who protests and seeks rectification. By means of the drawing and the line, which was dominant in her work, by depicting people's poses, she outlined the essence of the drama and the quintessence of protest she wanted to express.

Early Life and Family

Ruth Schloss was born on November 22, 1922, in Nuremberg, Germany, the second of three daughters of a Jewish family well integrated into German culture. Her mother, Dina [Elsass] Schloss, studied at Heidelberg University and worked as a kindergarten teacher. Her father, Ludwig Schloss, owned a paper and cardboard business and was an active member of the German Social Democratic Party. In 1937, after two years in Stuttgart, where Ruth attended the Waldorf school, the family fled from the Nazi Regime to Palestine.

Before Ruth Schloss had turned sixteen, she was accepted to the Bezalel Academy of Art in Jerusalem, where she studied painting and drawing. After graduating in 1942, she joined a collective of the Labor Zionist Hashomer Hatzair movement. Together the members of this collective were trained to establish a new A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutz, Lehavot HaBashan, in the northern Galilee.

Artistic Career

Though she was still a young artist, Schloss was invited to work as an illustrator at Sifriyat Poalim [The Workers' Library] publishing house in Tel Aviv. Her drawings and illustrations appeared in the children’s magazine Mishmar Leyeladim, periodicals affiliated with Hashomer Hatzair, and other children's books.

From 1949 to 1951, Schloss studied painting at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris. In 1952, after returning to her kibbutz, she married Benjamin Cohen, who became a professor of Ancient History at Tel Aviv University. In 1953, together with their one-year-old daughter, Raya, they were banished from the kibbutz because of their leftist views, which leaned towards Communism. They moved to Kfar Shmaryahu, next door to Schloss's parents, and in 1957, their second daughter, Nurit, was born. In 1965 Schloss left the Israeli Communist Party but continued to be an active painter struggling for peace and a just society.

From 1963 to 1983, Schloss painted in her studio in Jaffa. There she repurposed one room into a play area for the neighborhood’s impoverished children, both Arab and Jewish, whom she often depicted in her artworks. She continued to paint in her studio at Kfar Shmaryahu until 2008.

Ruth Schloss died on July 6, 2013, at the age of 91.

Since 1947, Schloss' artworks have been exhibited in many group and solo shows in museums and galleries in Israel and abroad. Her artworks are collected in the Tel Aviv Art Museum, Israel Museum Jerusalem, Museum of Modern Art Haifa, Art Museum Ein Harod, Umm al-Faham Art Gallery, the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, the Wichita Museum (Wichita, Kansas), and private collections.

Figurative Painting as Humanistic Position

From the very beginning of her career in the mid-1940s, Schloss expressed what her eyes saw. Her figurative paintings draw inspiration from the raw materials of life in her local environment. She directed the viewer's gaze toward Israel’s people and its "broken" landscapes with a rare sensitivity and courage unusual in her time: transit camp (ma'abara) landscapes, scenes of post-war destruction, uprooted Palestinian villages, traces of "abandoned property," and demolished neighborhoods in Jaffa.

A fundamental, irreplaceable element of Schloss’s work was the humanism that infused her consistent visual testimony. She explained: "I have tried to express in visual terms the tension between the desire to paint for its own sake and the need to react consciously" (quoted in Agassi, 1992).

Schloss’s first solo exhibition was held in 1949, at Mikra Studio Gallery in Tel Aviv. Her drawing Abandoned Village (1949), which depicted a post-war Palestinian village, appeared in the brochure for the exhibition, alongside scenes depicting the immediate vicinity of her kibbutz.

These early drawings present the unique line and style Schloss maintained throughout her long artistic career. The drawings project the sense of the moment; they preserve the freshness of quick sketches, but at the same time build upon a calculated structure and composition (Bar Or, 2006).

The offset print of an ink drawing, Mother and Child (1963), is a typical example of Schloss's images of feminine figures. It depicts reality and seeks reflection. The young mother's national identity seems unimportant; our attention is drawn to the merged inseparable image of the mother and her child, which accentuates intimacy, belonging, and closeness. Deviating from the traditional mother and a child pose of Western painting, the little girl is focused on the mother’s breast, gripping her nipple. This arrangement can point to the breast as a source of nourishment, but at the same time it hints at the mother’s eroticism and femininity. This suggestiveness can be related to the mother’s gaze, looking at something else, outside the depicted scene, a bit sad and a little defiant. Although the image portrays a sense of safety and intimacy, the image of the mother it presents is more complicated (Cohen Evron, 2023).

Mother and Child was part of an album of large reproductions of Schloss’s work. During the 1960s and 1970s, these reproductions were used to decorate private and public spaces in Israel. Like images posted widely online today, they made Schloss's artworks familiar to a diverse range of audiences (Bar Or, 2006).

Schloss remained a figurative painter even in the period when the visual arts were dominated by abstract painting and the “art for art’s sake” approach in the Israeli artistic establishment (which changed during the 2000s). Her characteristic drawing lines served to interpret the events she observed directly or through photographs, as a sort of seismograph (Dagon, 1992).

Schloss’s painting style has often been described as "Social Realism"(LeVite and Ofrat, 1980), a term for art that glorifies the reality of workers and aims to enhance social solidarity. Nevertheless, Bar Or (2006) points out that Schloss’s drawings do not obey the rigid rules of Social Realism. Instead of expressing epic heroism, her paintings distill universal justice from particular cases. They create painted reflections that, despite hanging silent on the wall, insist on crying out (Rabina, 2023).

While maintaining figurative painting as a humanistic position, Schloss’s artistic means and techniques changed over the years. From oil colors, used in the portrait of Nabya (1965), an old Arab neighbor who visited Schloss in her studio in Jaffa, she switched to acrylic colors. The bluish figure of The Hummus Eater (1988) is painted with force colored paintbrush using acrylic free from the heavy layering of oil paints. It portrays an ordinary man in the common act of eating hummus, but his eyes are sunken like black holes in his skull and refer to a different existence. The painting depicts a typical Israeli, who could be an Arab or Palestinian figure as easily as a Jew (Tamir, 2006).

Beginning in the early 1980s, Schloss’s artworks incorporated photographs and documentary material, using photographic prints as part of her paintings. But in her twilight years, she returned to basing her work on her unique drawing abilities. Woman Laying Down (1994) and Old Woman (1997) are among these paintings, which focused on monumental figures of old men and women, many in retirement communities (Dekel,2020). While the elders are not always depicted in miserable circumstances, the misery is of the beholder, the agony of observing how life ends (Mishory, 2001). Schloss’s monumental close-up depictions are filled with power, suffused with her experiences and the insight accumulated over the course of her long life (Danon Sivan, 2022).

Schloss’s Critical Gaze on Wars

Schloss's clear opposition to the violence and destruction caused by wars and her promotion of peace were expressed directly in her graphic works. During the 1950s and 1960s, Schloss designed political brochures, posters, and New Year greeting cards for United Democratic Women in Israel and The Committee for Peace, and in 1959 she contributed to the "Peace for the World" international album, printed by the art publisher Verlag der Kunst in Dresden, Germany.

An example of Schloss's graphic work is the poster Stop the American War in Vietnam (1966), in which she depicted with expressive lines a skinny Asian- looking woman with her baby tied on her back, looking at the remains of a corpse lying on the ground (Tamir, 2006).

Schloss's antiwar views also characterized her painting. She was one of the few Israeli artists who were not swept up in the euphoria of Israel’s victory in the 1967 war, as was much of the rest of the Israeli Jewish society (Tamir, 2006). Her drawing After the War (1967) belongs to a series depicting parts of burnt tanks, bits of corpses, various remnants and other objects carried by the wind of Sinai desert. These drawings were based on photos taken by Swiss photographer Ursula Gansser-Markus.From the 1960s onward, Schloss interpreted photographs she collected from newspapers, magazines, books, and photographers.

Beginning in the 1980s. Schloss incorporated photos into her painting using photographic printing, as she did in Soldier with Sabra Bush (1988). Schloss created the work during the years of first Intifada, the uprising of the Palestinians against the Israeli occupation. The printed sabra posed next to a painted well-equipped soldier, shown from his back, is part of the typical landscape. But the printed sabra, in equal size to the soldier, underlines its symbolic part in the Palestinian persistence and surviving (Tal Tenne, 2023).

To her paintings depicting the oppressive events of the Intifada, Schloss added a series of pictures expressing her despair and revulsion at the situation via metaphor. The Rhinoceroses (1989) is part of this series, showing the huge animals galloping forward and stamping out indiscriminately everything in their path. The series includes painting of wild dogs, as well as hyenas, vultures, and crows quarreling over remnants of carrion. Each animal Schloss chose represented for her certain traits and symbolized everything ugly in a society applying force against the powerless (Krymolowski, 2002).

Conclusion

Throughout Schloss’s long artistic career, her works indicated her preference for figurative painting, which is harnessed to represent the socio-political reality; painting that directs its gaze at the social margins and focuses on excluded and disempowered populations. Her ongoing engagement with the human existence of the helpless was depicted withpowerful means of expression. Because of her works usually using the feminine figure, Jew or Palestinian, who protests and seeks rectification her works form part of the feminist discourse and the peace movements in Israel.

Agassi, Uzi. “The Direct Statement in Ruth Schloss' Work.” In Ruth Shchloss: Retrospective 1942-1992, 122-136. Israel: Herzliya Museum of Art, 1992. [Hebrew]

Bar Or, Galia. “Circles of Affiliation.” In Ruth Schloss: Local Testimony, XXI-XXXI. Ein Harod: Museum of Art, Ein Harod, 2006. [Hebrew]

Cohen Evron, Nurit. “Mother and Child, Mother and Daughter.” In Ruth Schloss in Umm al-Fahm, 117-123. Israel: Umm al-Fahm Gallery, 2023. [Hebrew]

Dagon, Yoav. “The paintbrush as medium of protest.” In Ruth Schloss: Retrospective 1942-1992, 140. Israel: Herzliya Museum of Art,1992. [Hebrew]

Danon Sivan, Anat. Ruth Schloss: Protests on the Horizon, 2022. https://www.tamuseum.org.il/he/exhibition/ruth-schloss-protests-horizon/

Dekel, Tal. Women and Old Age: Gender and Ageism as Reflected in Israeli Art. Ra'anana: The Open University of Israel Press, 2020. [Hebrew].

Krymolowski, Miri. Ruth Schloss: Reacting to Reality, Works 1982-2002, Catalogue exhibition curated by Irit Levin, Miri Krymolowski, 2002. [Hebrew]

LeVite, Dorit and Ofrat, Gideon (1980). The Story of Art in Israel. Givatayim: Massada LTD, 1980. [Hebrew].

Mishory, Alik. “Expressive Reflections in Ruth Schloss' Mirror of Existential Reality.” In Ruth Schloss: The Last Years. Catalogue exhibition curated by Irit Levin, Doron Polak, Givatayim Theater, 2001.

Rabina, Doron. “A Breaking of Silence.” In Ruth Schloss in Umm al-Fahm, 132-134. Israel: Umm al-Fahm Gallery, 2023.

Tal Tenne, Nurit. 2023. “One Hundred Years since the birth of Ruth Schloss: ‘The Social-Humanist Conscience of Israeli Art.’” In Ruth Schloss in Umm al-Fahm, 136-152. Israel: Umm al-Fahm Gallery, 2023.

Tamir, Tali 2006. “Painting Against the Current.” In Ruth Schloss: Local Testimony, XXXIII-LXXXI . Museum of Art, Ein Harod, 2006.