Science in Israel

Data from a 2003 report revealed that women constituted only about twenty percent of all those engaged in science and technology in Israel. Awareness is growing that only through proactive efforts can gender equality be realized. In education, academia, and industry, women are becoming more involved in scientific fields, in large part due to the work of The Council for the Advancement of Women in Science and Technology, initiated in March 2000. The Council has been a driving force in a wide variety of activities, working with national and transnational bodies, and has catalyzed concerted and consistent policy and systematic action to further women in science and technology.

Background

In October 2003 the European Commission published She Figures, a survey on women in science and technology in member countries and associates (including Israel), which cited statistics and other data that provide a basis for measuring the progress towards equality of the sexes in these spheres. The study identified the following common trends, applied to all European states (including Israel):

- There are broadly equal numbers of men and women working in science and technology occupations when a wide definition of science and technology is examined.

- On the other hand, women are consistently under-represented as PhD graduates, as researchers (especially in the business enterprise sector) among senior university staff, and as members of scientific boards.

- Only one third of researchers in higher education and government research institutions are women. Furthermore, only fifteen percent of researchers in the business enterprise sector are women.

- The rates of increase are currently higher for women than for men PhD graduates and researchers in most countries and sectors.

In the mid-1990s, when Israel joined the European Research and Development (R&D) framework program, the country for the first time had to address the issue of gender differences, and then-Minister of Science, Matan Vilnay, adopted the European policy of advancing women in the field. In December 2000, the Israeli government established a Council for the Advancement of Women in Science and Technology, thus initiating properly organized government action of a kind that had previously existed only sporadically. Three years later, the council published a report on activities and on the situation at the time. The following data are among those included in the report.

In 2001, women constituted twenty-four percent of all senior academic staff at all of Israel’s higher education sector.

In 2000, women completing all degrees (bachelor, masters, or doctor) in hard sciences constituted twenty-five percent of all graduates.

In 2001, a survey of women managers in industry indicated that women constituted twenty-nine percent of all women in industry (not managers only). The latter constituted seventeen percent.

All the data may be summed up as revealing that women were only about twenty percent of all those engaged in science and technology in Israel.

In July 2002, the Lit. "assembly." The 120-member parliament of the State of Israel.Knesset proclaimed 2002–2003 the year of advancing women in science and technology, resulting in numerous activities. These included some twenty conferences organized by universities, colleges, and various organizations and attended respectively by teachers, scientists, academics, industrial workers, and the general public.

- Dedication of that year’s National Science Day (held annually on March 14, Albert Einstein’s birthday) to the topic of women in science and technology.

- Publication of a survey of public opinion on women in science and technology.

- Publication of a register of about 450 outstanding women academicians in a variety of scientific areas.

- Establishment by the Committee of Heads of Universities of a forum mandated to advance women scientists in academia.

All of these activities combined to arouse media interest and coverage of events related to the subject of women in science.

When people refer to equality between the sexes, the dominant approach is the liberal one, which maintains that, since no law prevents women from choosing to study science and nothing to stop them from advancing to senior positions, the statistics reveal a personal choice on the part of women and not discrimination of any kind. Hence there is no need for any special action other than ensuring that there are no discriminatory rules or regulations. This liberal approach refers to equal opportunity rather than equality in practice. It does not take into account a reality in which men and women are subject to different constraints, such as family and domestic responsibilities for children and/or elderly parents. The liberal approach also fails to take into account social attitudes that encourage males to go into difficult fields while females are encouraged to study the humanities rather than the sciences.

In recent years, the liberal approach has been increasingly deemed inappropriate and has been replaced by an awareness that only through proactivity can a change be brought about.

Women in Academia

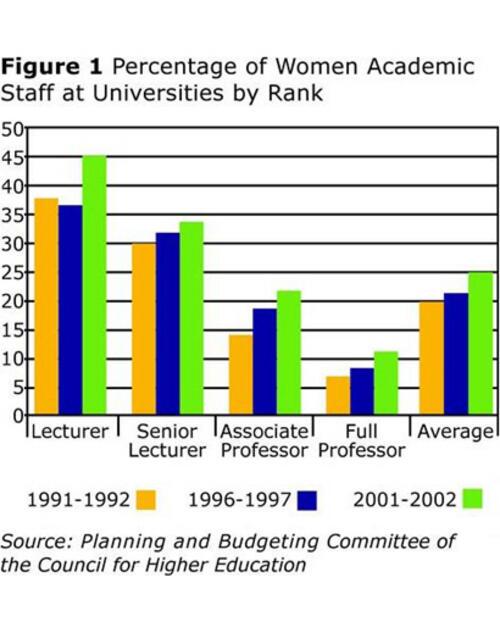

Figure 1 indicates the percentage of women in various senior ranks on the faculties of Israeli institutions (from lecturer to full professor) in the 1990s and at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

While the graph shows a gradual overall improvement, it nevertheless reveals that as the rank rises, the percentage of women decreases.

In the last decade of the twentieth century more than 360 faculty members were promoted to the rank of full professor, a rank that ensured membership in the university senate and various committees that have a major role in decision-making. Of these, women constituted only twenty percent.

Women’s status in academia is also apparent from the number of senior positions they occupy. Until 2006, no woman had ever served as a university president and only two had served as rector (academic head).

Women and Research Funds

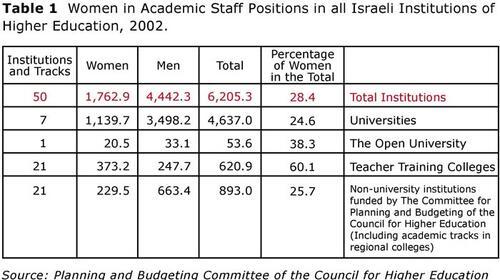

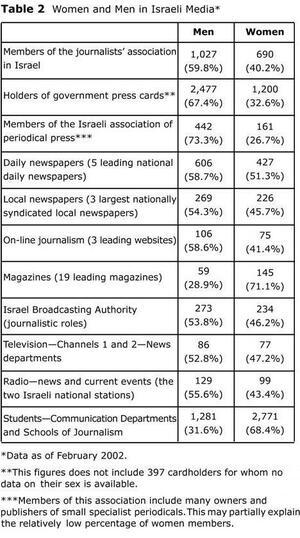

In general, fewer women researchers than men request funding for basic research and even fewer are successful in obtaining it (see Table 2). Partly this is due to excessive caution or modesty and partly to the unintended gender bias in the evaluation process.

Activities Designed to Advance Women

Publication of the data relating to the number of women faculty members led both to increased awareness and to a number of actions designed to improve the situation. These included the development of women and gender studies, which are an essential factor in increasing awareness of the existence of discrimination. Most Israeli universities now have a program in this field, ranging from a minor or first degree program to master’s degrees.

In addition, special scholarship funds were established in the area of women and gender studies, which stimulated and encouraged research in the field. Furthermore, as a result of advocacy by the Israel Women’s Network, beginning in 1988 universities appointed advisers to the president, whose function was to oversee the status of women at the respective institutions and ensure that there be no gender-based discrimination at any level. Since this custom was discontinued in some universities, a renewed demand was submitted via the Committee of Heads of Universities, whose members agreed to review their commitment to such appointments.

Age Limitations

Many research funds set age limits as a criterion for funding. While these limits appear to apply to both women and men, they in fact discriminate against the former, since many women—unlike men—take time out for child-bearing and child-rearing and are thus free to resume their academic career only at a later age. As a result of advocacy, at least one major fund (the Kreitman Fund) has abolished the age limitation.

Girls and Women in Education (From Elementary School to First Degree)

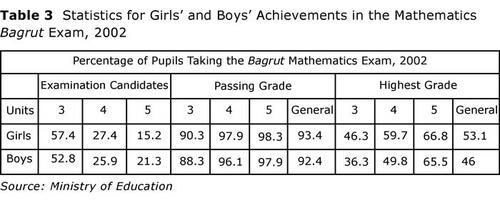

More girls than boys complete high school in Israel today. Seventy-five percent sit for the Bagrut school-leaving examinations (as compared with sixty-three percent of boys) and fifty-four percent successfully pass the examinations (as compared to thirty-eight percent of boys). For our purpose, the mathematics results are of greatest interest. Eighty-five percent of girl pupils take the math examination, as distinct from 83.3 percent of the boys. However, more boys take the highest, five-point, examination. Girls achieve higher grades at all levels, especially in the three- and four-point levels. See Table 3.

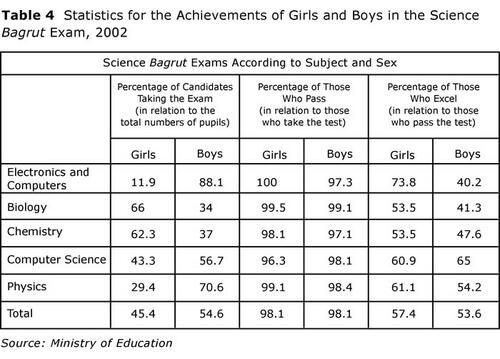

The percentage of girls taking the Bagrut examination in science is forty-five percent at all levels. They constitute sixty-six percent of those taking biology, sixty-two percent in chemistry, forty-three percent in computer science and only twelve percent in electronics. The percentage who pass is high for both sexes (ninety-eight percent), although the percentage of girls who achieve distinction in all sciences is slightly higher—fifty-seven percent to fifty-three percent of boys. See Table 4.

There are three times as many women teachers of science as men, but the higher the level of the school, the fewer women staff there are: five times as many women in elementary schools, but only twice as many in high schools. Thus even at school, pupils already learn that in a system that has undergone steady feminization, men are superior to women. There are 3.2 times as many women teachers as men, but only 1.4 times the number of women amongst school principals; at the high-school level the number of male principals is 1.3 times greater than that of women. (These figures relate to the 1999–2000 school year for the Jewish educational system.)

The girls’ success in the Bagrut science examinations proves that the problem of lower numbers in the sciences is a result of socialization rather than aptitude. In order to change the former, a number of intervention projects have been developed. With the aim of encouraging girls to study science and technology in high school and at university and eventually to make this their profession, the projects seek to increase motivation and even to provide direct support and tutoring. Some of the projects involved mentoring by women academics, others involved the participation of parents and teachers.

Some projects train women in post-high school science and technology studies, one of which prepares the participants for military service in the Communications Corps and in the Signals and Electric Corps.

Women, Science, and Technology in the Israel Defense Forces

Primarily for reasons of personnel needs, there is considerable awareness of the importance of integrating women in the scientific and technological areas in the Israel Defense Forces.

The Academic Atudah enables participants to study for a bachelor’s degree in a variety of subjects (not only scientific or technological) prior to enlistment. There has been a steady increase in the number of women participants from seventeen percent of all participants in 2000 to twenty percent in 2001 and twenty-three percent in 2002.

In addition, there are a number of prestigious projects that combine military service and studies, such as the Talpiot Project, which combines bachelor degree studies in physics, math or computer science, with training for a wide range of military service. All those who successfully complete the course enter the IDF as officers. In 2002 women constituted 23 percent of the participants, who have to commit themselves to five years of IDF service.

Since its very beginning in 1996, the IDF has also been a partner in “The Future Generation of Industrial Hi-Tech,” an intervention project operated in conjunction with high-tech companies, which seeks to encourage junior-high school pupils, and especially girls, to elect science and technology studies. Since 2002, the IDF has also been among the industrial participants, providing a work environment for pupils at the schools it has “adopted.”

In recent years there has also been a slight increase in the number of women in the career army who have been trained to serve in maintenance units of the Air Force and as electricians, motor mechanics, helicopter mechanics and in anti-aircraft artillery. In 2002 the General Staff recommended a significant increase of women in these frameworks. However, the number of women NCOs involved in maintenance (five percent) is low in comparison with previous years.

The Council for the Advancement of Women in Science and Technology

The Council for the Advancement of Women in Science and Technology was initiated in March 2000 by Professor Hagit Messer-Yaron, at the time the Chief Scientist of the Ministry of Science, Culture and Sport, and advocate Naomi Liran, who headed the Authority for the Advancement of Women at the Prime Minister’s Office. In November 2000 the ministerial committee for science and technology decided to establish the Council; its decision was ratified by the government in December. While the Council members are all representatives of government and other national agencies, its advisory forum includes women from industry, university lecturers in women’s studies and representatives of women’s organizations such as WIZO, the Israel Women’s Network and Na’amat.

The functions of the Council include consciousness-raising among educators and the public at large, furthering projects designed to encourage girls and women to study science and technology, operating a website to publicize matters related to its area of responsibility, publication of an annual report detailing current data, and collection of information on ongoing activities related to women in science and technology.

The Council meets frequently, in plenary sessions and in a series of subcommittees on education, academia and industry, as well as in ad-hoc forums. It has held a series of conferences aimed both at raising public awareness of the issues and at creating networks. In addition, the Council has been the catalyst for creating a scholarship fund for outstanding women university students who are studying in departments where there is a paucity of women. In return, these students volunteer one hundred hours to activities designed to encourage schoolgirls to take up science and technology, such as tutoring junior-high and high-school pupils in mathematics or physics. Thus they are also serving as role models.

The Council has understandably been a driving force in a wide variety of activities, working vis-à-vis national and transnational bodies, and has catalyzed concerted and consistent policy and systematic action to further women in science and technology.

This article is based on the Hebrew publication Women and Science in Israel: A Status Report, by Professor Hagit Messer-Yaron and Shirli Kahanovich. Published by the Council for the Advancement of Women in Science and Technology in December 2003.