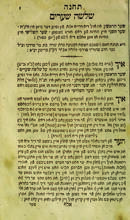

Seder Mitzvot Nashim

Seder Mitzvot Nashim refers to the genre of literature in Ashkenazic and Italian communities that explained the specifics of how women should observe the commandments that were particularly associated with them. This handbook was reprinted many times, most famously by Rabbi Benjamin Aron Slonik, whose 1585 version of Seder Mitzvot Nashim was a veritable best seller of the pre-modern age. Slonik’s work is characterized by a combination of detailed explanations of how to observe the law and ongoing descriptions of the rewards and punishments that await a woman who either observes or disregards the law. The handbook addresses all aspects of a woman’s life and included advice on how to successfully adhere to the law.

Background

The title Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.Seder A biblical or rabbinic commandment; also, a good deed.Mitzvot Nashim (the order of women’s precepts) refers to the genre of literature in Ashkenazic and Italian communities, written in the vernacular. Such compositions explained the specifics of how women should observe the commandments that were particularly associated with them. The earliest extant copy in this genre was prepared for a woman in the early sixteenth century, suggesting that such works already existed in the late fifteenth century. While all such texts focus on the laws of niddah (menstruation), most also deal with the lighting of candles on the Sabbath and festivals, as well as with the taking of During the Temple period, the dough set aside to be given to the priests. In post-Temple times, a small piece of dough set aside and burnt. In common parlance, the braided loaves blessed and eaten on the Sabbath and Festivals.hallah (see Num. 15:17–21) and other aspects of domestic life.

The first published text of this type was prepared by David ha- Priests; descendants of Aaron, brother of Moses, who were given the right and obligation to perform the Temple services.Kohen, whose identity is uncertain. The Yiddish text, which appeared in Cracow in 1535 under the title Asharot Nashim, contained an index to help readers locate information. According to the author, the book was not an original creation but was based upon two earlier Hebrew handbooks for women, one written by Rabbi Judah ha-Levi Minz of Padua (c. 1408–1506) and the other by Rabbi Samuel of Worms (d. after 1542). That rabbis of such high stature were involved in writing legal vademecums for women indicates that rabbis attached importance to the endeavor. The publication of such works in the vernacular is proof that the opposition to popularization of the law for women in Yiddish voiced by Rabbi Jacob ben Moses ha-Levi Moellin (the Maharil, c. 1360–1427) had little long-term influence.

Rabbi Slonik’s Work

Other Yiddish versions of the handbook were printed in Venice during the course of the sixteenth century but the most important such work was prepared by Rabbi Benjamin Aaron ben Abraham Slonik of Grodno (c. 1550–c. 1619), a rabbinic scholar of the first rank. A veritable best seller of the pre-modern age, Seder Mitzvot Nashim (Eyn Schoen Frauenbuechlein) was published in Cracow in 1577, 1585, and 1595 and in Basel in 1602. It continued to be reprinted in the German territories over the next approximately one hundred and fifty years. In the early seventeenth century it appeared in an Italian translation that reflected certain Italian sensibilities and was republished a number of times with emendations. A manuscript version of a totally different text for women in Judeo-Italian was never published and as a result simply languished.

Slonik’s work is characterized by a combination of detailed explanations of how to observe the law and ongoing descriptions of the rewards and punishments that await a woman who either observes or disregards the law. While particular emphasis is placed upon observing the law so that one’s children not suffer, there are also extensive depictions of both the glories and horrors of the next world. Stories that emphasize the rewards enjoyed by pious women of the Bible as a result of their correct observance and proper thoughts during sexual intercourse are part and parcel of the work.

Going well beyond earlier vernacular texts, Slonik not only conveyed to women the basic rules of the laws of niddah, such as what is prohibited between husband and wife while a woman is a menstruant, but more specifically instructed them on the relatively complicated issue of how they should calculate their menstrual cycle for The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhic purposes (i.e., on what day or after what sort of physical phenomenon they would have to abstain from physical contact with their husbands: kevi’at veset).

In questions of hallah, as in other matters, Slonik offered women very practical advice. Drawing heavily on the recently published Shulhan Arukh, he instructed them on how to measure the necessary volume to know whether or not a particular dough was obligated to have hallah taken from it. Slonik realized that many women, young brides in particular, did not observe the laws associated with women properly due to sheer ignorance, while others, who were unsure about the law, were needlessly stringent upon themselves in matters of ritual purity. Other women were simply embarrassed to ask a rabbi about their menstrual bleeding while those who lived in outlying communities could not ask for rabbinic guidance because there was no one to ask. In making such detailed and extensive information available in Yiddish, Slonik offered women the possibility for far greater religious independence than they previously had. Although Slonik specifically noted that not all women could read, he expected husbands to read the book to their wives or that women would use it to educate each other. Thus, with access to a handbook, women could solve some problems for themselves. Still, Slonik did not urge women to rule independently but rather reminded them to ask a rabbi when possible.

The genre was not without other practical guidance and advice. Women were told to feed their animals before themselves, what prayers to say and to keep their houses tidy so that the Shekhinah would be able to dwell therein; and they were urged not only to give charity but to do so gracefully. Women were also reprimanded about cursing people and taking oaths too freely, matters that appear to have been problematic at the time. Instructions on child rearing also appear in the book, with a reminder to women that they were responsible for teaching their children proper religious behavior. Women were also told to help their husbands lead a religious lifestyle, be it by preparing the house for the Sabbath or by gently urging them to study. As Slonik repeatedly wrote to his female readers, “Therefore, dear daughter, you certainly see that everything depends on the woman.”

Baumgarten, Jean. Introduction á la littérature yiddish ancienne. Paris: 1993.

Goldwasser, Morris. Azhoras Noshim: A Linguistic Study of a Sixteenth-Century Yiddish Work. With a postscript by Chava Turniansky. Working Papers in Yiddish and East European Jewish Studies 33. New York: 1982.

Modena Mayer, Maria. “Il ‘Sefer miswòt’ della Biblioteca di Casale Monferrato.” Italia 4.2 (1985): i–xxi, 1–107.

Romer-Segal, Agnes. “Editions of Sefer Mitzvot Nashim in Yiddish in the Sixteenth Century” (Hebrew). Master’s thesis, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, 1979.

Ibid. “Yiddish Works on Women’s Commandments in the Sixteenth Century.” In Studies in Yiddish Literature and Folklore. Jerusalem: 1986, 37–59.