Bella Spewack

Bella Spewack, in collaboration with her husband Sam, is known for writing some of the most memorable works of musical theater history. Spewack was born in Transylvania and lived an impoverished childhood in New York's Lower East Side. In 1922, she married Sam Spewack, and the two began their masterful collaborations. Their librettos, such as Leave It to Me and Kiss Me Kate, were characterized by fast-tempo witty remarks and biting irony. The Spewacks wrote screenplays for several 1940s Hollywood hits, including My Favorite Wife and Weekend at the Waldorf. The couple contributed to several Jewish causes. In 1946, as a representative of the United Nations, Bella covered the distribution of food in Eastern Europe, and in 1960, they founded the Spewack Sports Club for the Handicapped in Ramat Gan, Israel.

“Just about the ages of 10 and 12, and even much more before then, there burns brightly in every ghetto child’s brain the desire to see what lies without the ghetto’s walls,” playwright Bella Spewack wrote in her diary in 1922. When she made this observation, Spewack was in Berlin, Germany, with her husband, Sam Spewack, who was working there as a reporter for the New York World. She was only twenty-three years old, but already on the way to a successful career in writing and show business. These early experiences are chronicled in Streets: A Memoir of the Lower East Side.

After reading her diary, it is clear that most of Bella’s childhood and youth was a struggle to leave the Lower East Side for a better life uptown. A better life did not mean simply material things, but also, perhaps even more importantly, a proper education and a career.

Early Life and Family

Bella (Cohen) Spewack was born on March 25, 1899, in Transylvania, at the time a province of the vast Austro-Hungarian Empire, now part of Romania. Jews from that region, especially those from urban areas, were generally better educated and more cultured than their brethren from the hinterlands of Poland and Russia. Unlike the shtetl Jews of Galicia and the Ukraine, the more urbanized Austro-Hungarian Jews possessed some of the sensibility of Central Europeans: they were cosmopolitan with an eye for elegance and aesthetics.

These qualities were clearly evident in Bella and in her mother, Fanny Cohen. In fact, Bella owed a great deal to her mother. Her parents were already divorced in 1902, when Bella and her mother arrived in New York. Fanny Cohen remarried in 1911. Bella’s stepfather was Noosn Lang, a boarder in their apartment on Lewis Street, who was a pants presser in the garment district. A year later, her half-brother Hershey was born, but he died of an incurable disease at age five. Daniel, a second half-brother, was born in 1913. Like Bella, he too grew up fatherless because Lang, a mean, abusive husband, abandoned his family soon after Hershey’s death, while Fanny was pregnant with Daniel. It would be an understatement to say that 1912 and 1913 were tumultuous years for Bella: she experienced a death, a birth, parental separation, graduation from Washington Irving High School, and the start of her career as a reporter for the Yorkville Home News. (Her struggle to become a writer is reminiscent of another famous immigrant author, Anzia Yezierska, who wrote of her aspirations in the autobiographical novel Bread Givers.) It is not surprising that Bella chose this profession—her memoir of her early teens clearly reveals a keen eye for human behavior, wit, and good writing skills. This position soon led to jobs as publicity agent and reporter for a string of newspapers, including The Call.

The Spewack Writing Team

In 1922, she married Sam Spewack, a foreign correspondent for the New York World. After a four-year stint in Europe, the two began writing some of the most memorable lyrics in musical theater history. Two librettos, Leave It to Me (1938) and Kiss Me Kate (1948), were Cole Porter collaborations, the first play an adaptation of a 1932 Spewack drama, Clear All Wires, and the second, a modern version of The Taming of the Shrew. In addition, the Spewacks wrote screenplays for several Hollywood hits of the 1940s: My Favorite Wife (1940), with Cary Grant, and Weekend at the Waldorf (1945), with Ginger Rogers and Lana Turner. In 1948, Kiss Me Kate, the movie, had its premiere in New York. Their first play, The Solitaire Man (1927), was seen only in Boston, but Boy Meets Girl (1936) ran for 669 performances in New York.

Since they worked as a team, it is, of course, impossible to evaluate one without the other. However, it is widely accepted that Sam created the plot and action, while Bella wrote most of the dialogue. George Abbott, the legendary Broadway director, said that the Spewacks “know how to write lines which are not only funny to read but which crackle when spoken in the theatre.” True, some of their serious drama received mixed reviews, but the negative response was mostly to the plot, not the dialogue. Anyone familiar with the Spewack comedies is struck by the liveliness of the text, the witty remarks, the biting irony, and the fast tempo.

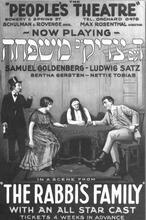

The Spewacks’ early plays—Poppa, Spring Song, and War Song—deal with a variety of social issues, among them problems facing new immigrants, some of whom are Jewish. They focus on the clash of cultures, the effect of Americanization on traditional ways, and disenchantment with the elusive American dream. These themes are usually built around some family crisis—failed marriages, mixed marriages, duty to parents. Who better than Bella Spewack, who has “seen it all,” to write about such things? These concerns bring to mind many of the Jewish plays written in the 1920s and 1930s by such established dramatists as Clifford Odets, Elmer Rice, and Aaron Hoffman. Most of these plays failed at the box office. In times of economic hardship, people seem to prefer comedies over serious drama. The Spewacks recognized that need and devoted themselves to lighter matters, generally based on the formula: “Boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl”—hence, Boy Meets Girl and Kiss Me Kate, their biggest hits on Broadway and in Hollywood.

Later Life

Though in later works the Spewacks distanced themselves from their Jewish roots, the couple contributed time and money to a variety of Jewish causes, mostly involving children. In 1946, as representative for the United Nations, Bella Spewack covered the distribution of food in ravaged Eastern Europe, where so many Jewish communities lay in ruins. In 1960, Bella and Sam founded the Spewack Sports Club for the Handicapped in Ramat Gan, Israel.

Except for a few minor pieces, the Spewacks’ creative career ceased in the mid-1950s. Occasionally, they would appear in public with a Broadway director or famous musician, but after Sam’s death in 1971, Bella’s activities were confined to traveling to see productions of Kiss Me Kate and walking the fashionable midtown neighborhoods near Carnegie Hall—not bad for a poor Hungarian girl from the crowded tenements of the Lower East Side.

Bella Spewack died on April 29, 1990.

Drorbaugh, Elisabeth. “Bella Spewack.” In Jewish American Women Writers, edited by Ann Shapiro (1994).

EJ.

UJE, s.v. “Spewack, Samuel”.

WWIAJ (1938). For a complete bibliography, see Drorbaugh’s essay, which includes citations of media reviews, movie and television scripts, and librettos of musicals.