Sports in Austria 1918-1938

This article gives an overview of the participation of Jewish women in Austrian sport from the Habsburg monarchy to the present day. Drawing on selected biographies of sportswomen and functionaries, and with a regional focus on the capital city of Vienna, it explores the double relationship between female emancipation and Jewish self-assertion in an environment that had long been male-dominated and anti-Semitic. Special attention is paid to the beginnings of bourgeois women’s sports from the 1890s onwards, the national Jewish gymnastics movement, and the Hakoah sports club, whose legendary swimmers refused to participate in the 1936 Olympic Games in Nazi Germany. Also discussed is the participation of Jewish girls and women outside Jewish sports, for example in working-class sports and alpinism.

Introduction

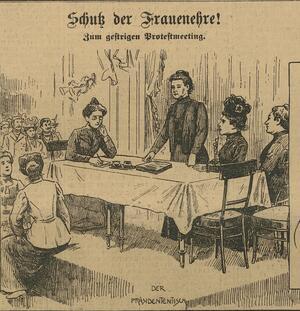

While the history of women’s sports in Austria has only been partially chronicled, the 1890s are regarded as the foundational years. At that time, the public discourse on women participating in sport was strongly linked to such issues as general emancipation, the attainment of political rights, and clothing reforms, and was firmly opposed by male moralists, sports officials, and journalists.

These debates took place in various newspapers and specialist media, such as the influential Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung, but also in the form of essays and lectures. Austria’s first female Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Bertha von Suttner, fought for equality and denounced the cliché of “female weakness.” One statement by Viennese women’s rights activist Rosa Mayreder (1901, 504), that the bicycle had “contributed more to the emancipation of women from the higher social classes than all the aspirations of the women’s movement put together,” is still widely cited.

The sports in which women could initially participate generally corresponded to the social understanding of female sportsmanship and body ideal. Factors such as grace, aesthetics, effort, and competitiveness decided whether a sport was acceptable for women—and in Austria at the end of the nineteenth century, this meant primarily bourgeois women. This helps to explain why women found easier access to sports such as ice skating, swimming, tennis, and hiking. Around the turn of the century, high-altitude tourism started to become popular among women, and some women joined skiing clubs and even participated in competitions. The first skiing competition in Central Europe to include women was held in Mürzzuschlag, Styria, in 1893.

One eloquent advocate of women’s sport and the clothing reform necessary for its practice was the young Jewish intellectual Else Spiegel (1879-1907). The journalist, author, and women’s rights activist can be considered part of a secular, culturally open-minded Judaism. In her article “Abrüsten!” (“Disarmament!”), which she wrote at age 20 for Dokumente der Frauen, a magazine for members of the progressive Austrian women’s rights movement, Spiegel praised the American Health Protection League’s campaigns against wasp waists, stuffed hips, long skirts, and heavy hats and confidently called for practical clothing for sports (Spiegel 1900, 725). In general, she ascribed an “immediate value” to sports in the fight against “fashion follies,” which was “slow, quiet, but intense,” and listed the most popular sports that Austrian women already practiced during those years: “Anyone who wants to get on a bike, climb glaciers, row, or sail, who wants to take up a racket, strap on skates, or the more fashionable skis, cannot be tied up in a long, tight, constricting dress and put on a big, heavy, decorated hat. . . . Lightly dressed, in a comfortable shirt blouse and a low hat or cap, the young lady can ride, cycle, row, climb mountains, fence, perform gymnastics, run, jump; she can do everything in it. She can move and movement is everything; progress, life, overcoming all obstacles” (726).

Antonie Graf: A Pioneer of Women’s Sports

The life of pedagogue Antonie Graf (1845-1929) exemplifies the beginnings of women’s sports in Austria. Born Antonie Machold, she converted to Judaism in 1870 when she married the journalist Moriz Graf. Prior to her marriage, she ran a girls’ education institute in Vienna, then an agency for governesses. In the Jewish community, after 1892 Graf became one of the most important proponents of the Ferienheim (Retreat Colony), the largest Jewish women’s charity at the turn of the century, which enabled needy and “weak” Jewish children to vacation in the countryside. Graf published texts on women’s and social issues in magazines of the Jewish community, not least in Bloch’s Oesterreichische Wochenschrift. Her journalistic and civil society activities were not limited to Jewish circles, however; she was also prominent in the National Council of Women – Austria, an important federation within the bourgeois women’s movement in Austria-Hungary founded in 1902, where she helped promote women’s professional activity.

In 1894, Antonie Graf founded the Ersten Schwimm-Klub für Damen in Wien (First Swimming Club for Ladies in Vienna), which a year later became the women’s section of the swimming club Austria. The aim of Graf’s club was “to popularize regular swimming among women and girls” (Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung, December 18, 1904, 1564), but top sporting achievements were also sought after. In 1908, Graf founded the Damen-Schwimmklub Wien (Ladies’ Swimming Club Vienna). When the Austrian women’s 4x100m relay team won the bronze medal at the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm, it included Grete Adler, Fini Sticker, and Klara Milch–three swimmers from Austria and the Ladies’ Swimming Club Vienna who came from Jewish families (likely in Milch’s case). In lectures and essays with titles like “The Water as the People’s Educator,” Graf devoted herself to the promotion of women’s sport, which she claimed would give back to the body “what is taken away from it by long sitting on the school bench, the stooped posture in handicrafts, etc., and finally sitting still in the house” (Graf 1912, 67). In contrast to her philanthropic work for Jewish children, questions of Judaism did not play an explicit role in these activities, and the swimming clubs she founded were not part of the Jewish National movement.

Jewish National Gymnastics Clubs and Gymnasts

The founding of specifically Jewish gymnastics and sports clubs in Austria should mainly be understood as a reaction to an anti-Semitic environment. When the Erste Wiener Turnverein von 1861 (First Viennese Gymnastics Association of 1861) introduced a clause requiring that members be “Aryan” (“Aryan paragraph”) in 1887, its former Jewish members co-founded the Deutschösterreichischer Turnverein (German-Austrian Gymnastics Association). In 1897, Jewish national students at the University of Vienna founded the Turnverein jüdischer Hochschüler (Gymnastics Club of Jewish College Students), which, after being renamed the Erste Wiener Jüdischer Turnverein (First Viennese Jewish Gymnastics Association) in 1899, also accepted female members. The founders were encouraged not least by Max Nordau’s concept of “muscular Judaism,” which he introduced in a speech at the Second Zionist Congress in 1898. “Muscular Judaism” was intended to provide an answer to the stigmatization of the Jewish body as weak and to establish the gymnast as a fighter for a Jewish collective. It fed on the models of the German gymnastics movement and the Slavic gymnastics organization Sokol (“Falcon”), as well as the Muscular Christianity of the British Empire. Ideas of a homosocial Männerbund (male association) and the masculinization of Jewish bodies did not necessarily preclude a certain amount of female participation, however. Earlier than the German National gymnasts, the new Jewish gymnastics clubs in Germany and Austria—which were jointly organized into the Jüdische Turnerschaft (Jewish Gymnasts’ Association)—already allowed women full club membership before the First World War. They were also more progressive about the public visibility of female gymnasts and the expansion of gymnastics exercises for women. At the Third Jewish Gymnastics Meet, which took place in Vienna in 1907, female gymnasts—members of the First Viennese Jewish Gymnastics Association—performed for the first time in public at an association day.

One of the few voices advocating for female Jewish gymnasts during those years whose writings have survived was Hedwig Donath (1884-1969). Born in Bratislava, Donath studied medicine in Vienna, where she received her doctorate in 1909. As a student, she was a board member of a “Jüdischer Mädchenklub” (Jewish girls’ club) and was active on the ball committee of the Jewish National student fraternity Kadimah. She published several articles in the Jüdische Turnzeitung, the journal of the Jewish Gymnasts’ Association, including a fable in which gymnastics equipment discussed the meaning of Jewish gymnastics clubs and describe them as a place where gymnasts can be “pure and unadulterated Jews” (Donath 1906, 121). In another essay, Donath discussed women’s participation in public gymnastics competitions on the basis of a fictitious argument between two ancient Greek lovers about female athletes in Sparta and Athens (Donath 1909). Although Donath pleaded for an all-female sports audience so as not to expose women to the pejorative judgment and sexualized gaze of men, later in the same essay, she wrote enthusiastically about a public gymnastics display put on by Jewish gymnasts at the 1909 Gymnastics Meet, where women had performed in post-reform clothing for the first time: “The impression will always remain unforgettable to me, how the Berlin ladies marched in their original, chic, and discreet costumes, tightly but gracefully under the sounds of music, silently divided into six groups without command and two groups each performed their exercises in the most exact manner on parallel apparatuses—was it the fact that they performed the exercises without any male help, was it the precise execution of the exercise itself, or finally the awareness that a woman had organized and directed the whole thing, or was it everything together that impressed me so powerfully?” (211).

The Sportclub Hakoah

It was from this circle of Jewish gymnasts and Jewish student associations that the Sportclub Hakoah formed in Vienna that same year. Its aim, set out in its founding appeal, was to achieve the “physical uplifting of the Jewish people,” not through gymnastics, but through the booming new sports—especially soccer. At that time, however, Jewish National or Zionist positions represented a minority within the heterogeneous Jewish population of Vienna. A large proportion of the Jews born in Vienna or who moved to Vienna from Bohemia, Moravia, and Hungary in the second half of the nineteenth century saw themselves as part of a German cultural community. This view was also evident within sports. For example, the lawyer Otto Herschmann—who left the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde Wien (Vienna Israelite Community; IKG) in 1895, medaled in the Olympic Games of 1896 and 1912, and later became president of the Austrian Olympic Committee—argued that sports should be used as a “cosmopolitan means of unification” and should be “in the service of the assimilation of the Jews” (Herschmann 1904, 26). But especially among the Jewish immigrants from Galicia and Bukovina, who before the First World War made up about one fifth of Vienna’s Jewish population, Zionism found many supporters—and the Jewish National gymnastics and sports clubs became the “most important Zionist youth organizations” (Rozenblit 1983, 166). Until the early 1930s, the IKG was dominated by the Austrian-Israelite Union, which was politically and culturally liberal but conservative in religious matters. Apart from the secular Zionists, the two largest Orthodox groups, the “Hungarian” Agudah and the “Polish” (Galician) Orthodox, who were closer to Zionism, also occupied a minority position (Pass Freidenreich 1991, 116). Almost no sources on the participation of Orthodox women in gymnastics and sports have been handed down, apart from school sports, which was also introduced in principle for girls in Austria in 1869, and finally became compulsory in 1918.

Jewish Alpinists

With regard to the participation of Jews in alpine sports and skiing, the picture is ambiguous. On the one hand, the proportion of Jewish members in some alpine associations was high; on the other hand, especially in the years after 1918, alpinism became an anti-Semitic battlefield. Numerous Austrian sections of the Deutscher und Oesterreichischer Alpenverein (German and Austrian Alpine Club) introduced “Aryan clauses” during these years—including the Austria section, of which, according to estimates, around a third of its members were of Jewish origin in 1921. The Austrian Ski Association also had an “Aryan clause” after 1923, which led to the foundation of the competing Allgemeiner Skiverband (General Ski Association), in whose competitions Jewish female skiers also successfully participated.

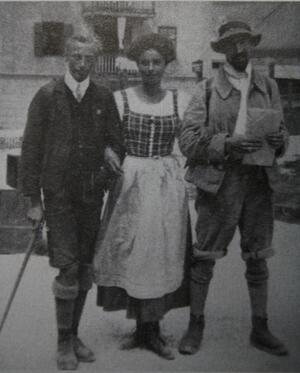

In reaction to the anti-Semitic exclusions from the Alpine Club, the Donauland section was founded in 1921, which took in many of the outcast members. That same year, Emmy (Eisenberg-)Hartwich (1888-1980), who came from an acculturated bourgeois Jewish Viennese family, gave a lecture within the section on “The Woman in the Mountains” (Hartwich 1924). Hartwich, who was already among the Austrian climbing elite before the First World War, was considered a very modern figure and regularly wore trousers on her hikes at that time. In 1914, she married and converted to Protestantism. In her lecture, which Hartwich called a “cheerful chat,” she tried to allay male fears of a female intrusion into alpinism. Although she said women lacked an innate sense of orientation and “skill in rope usage,” and the question of who carries the ladies’ rucksack remained a contentious issue, she said that women possess “all other mountaineering qualities.” On the basis of her own experiences, Hartwich described a partnership on the rope, whose clear division of roles between guide and guided can be read as “(self-)oppression” (Günther 1998, 300), but which also reveals the limits of female emancipation in the contemporary discourse of bourgeois mountaineering. “[T]he woman really finds in the mountains what she was created for: the domination of a guide to whom she likes to subordinate herself, and the relatively effortless, exciting, and pleasurable achievement of her goal—in this case, the mountain summit” (Hartwich 1924, 28).

The Battlefield of Identity Politics: Between Workers’ Sports and Fascism (1918-38)

The breakup of Austria-Hungary and the establishment of new, ethnically defined nation-states represented a shock to the status of the Jewish population of the former multinational empire. At the same time, however, the emergence of the democratic republic of German Austria in the autumn of 1918 enabled the right to vote and other political and social rights for women. Vienna was ruled by the Social Democratic Workers’ Party (SDAP) from 1919 until the elimination of democracy in 1933-34 by the authoritarian federal government of Engelbert Dollfuss.

In the ranks of the Social Democrats, many top officials were of Jewish descent, and since the SDAP resorted to anti-Semitism as a political strategy less often than the other major parties in Austria, it also had many Jewish voters, despite an agenda aimed largely at assimilation. Jewish girls and women were also active in working-class sports, which in the political conflicts of the 1920s and 1930s were organized autonomously in parallel to the bourgeois sports clubs and associations. There were also Jewish participants in the Second Workers’ Olympics, which took place in Red Vienna in 1931 and was attended by delegations representing Hapoel from Palestine and the Jewish workers’ federation Jutrznia from Poland, among other groups. In any case, the Social Democratic women’s movement saw the area of body culture as an important field of activity: the New Woman meets the contemporary phenomenon of sports girls. In 1929, feminist officials from the Arbeiterbund für Sport und Körperkultur in Österreich (Workers’ Association for Sport and Physical Culture in Austria; ASKÖ) implemented a women’s sports program in the Socialist Workers’ Sports International (SASI), which was intended to put sports in the service of emancipation.

Soccer was explicitly excluded from the sports that were eligible for support. When the Social Democratic consumer cooperative wanted to set up soccer teams for girls in 1933, they were brusquely rejected by the chairman of the ASKÖ, the leading SDAP politician Julius Deutsch, because “this sport is not suitable for the constitution of girls” (VGA, Party Offices, box 1, folder 6, June 9, 1933). Nevertheless, from 1936 to 1938, there actually was a women’s soccer league in Vienna, if only in bourgeois sports: the 1. Österreichische Damenfußball-Union (First Austrian Women’s Football Union), whose chairwoman was the department store owner Ella Zirner-Zwieback (1878-1970), a prominent public figure in Viennese Jewish life. Female Jewish sports officials were otherwise mainly found in swimming: between 1918 and 1938, there were ten women on the Hakoah board of directors, for example. Overall, however, the number of Jewish women among sports officials in the interwar period was less than five percent of that of Jewish men.

With the exception of soccer, ice hockey, heavy athletics, or shooting, many women were members of Viennese sports clubs at that time. In the popular sports such as swimming and ice skating, almost half of the active club members were female in 1929; in the gymnastics clubs, the figures were comparable. This also applied to Jewish National clubs: among the gymnasts under the umbrella of the Makkabi organization, 53 percent were women in 1935. Of the 1,568 total members of Hakoah, which at that time operated several departments that were independent under the association’s bylaws, women made up 32 percent. In the Hakoah swimming club, this figure was 45 percent, a large proportion of whom were children and young people.

Internationally Successful Swimmers

In the years after 1918, Hakoah developed into a large all-round sports club, which in most sections—with the exception of soccer and heavy athletics—specifically included female members. The club tried to achieve its agenda of Jewish emancipation through muscle power both through the broad participation of many young members and through high-profile excellence in popular spectator sports. In men’s sports, the achievements of the soccer team, which won the first professional league in the soccer-mad city of Vienna in 1924-25 and became a figurehead of the Zionist movement through numerous tours in Central and Eastern Europe and the United States, are notable here. In women’s sports, it was the Hakoah swimmers in particular who rose to become early sports stars.

But in the years between 1918 and 1938, the sports participation of the Jewish population of Vienna, which at that time made up about ten percent of the total population, was not limited to the Jewish National clubs. This can be seen, for example, in the fact that the membership of the Wiener Eislauf-Verein (Vienna Ice Skating Association; WEV) was reduced by half after the Anschluss with Germany in 1938 and the exclusion of Jewish members (Meisinger 2017, 112).

Almost all large sports clubs that did not have anti-Semitic “Aryan clauses” had active members and officials from Jewish families. Depending on the local, political, and cultural orientation of the clubs, participation enabled the respective individuals to temporarily make “Jewish difference” (Silverman 2012) disappear, or to consciously emphasize Jewish identity. Unlike in Germany, however, Hakoah was a highly visible anchor of Jewish pride in the booming popular and mass culture of sport. In retrospect, stories of the female fan base and their own sporting activities in Hakoah and other smaller Jewish National sports clubs were among the most important memories for many Jewish women who left Vienna, according to interviews conducted by the Leo Baeck Institute (1998, 1999, 2003, 2008) and Centropa.org (2002, 2003). Even for girls who did not come from avowedly Jewish families, participating in sports at Hakoah became a decisive moment in the search for Jewish identity in an anti-Semitic environment. As the swimmer Elisheva Susz describes it in Yaron Zilberman’s film Watermarks (2004): “I had no connection to Judaism, like a little Gentile girl who, at 15, joins a sports club because she can swim well. That’s all. Later it had a much more profound meaning.”

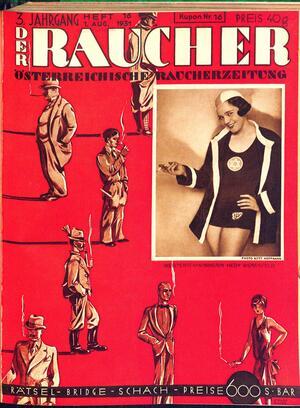

Successful swimmers such as Hedy Bienenfeld (1907-1976) and Fritzi Löwy (1910-1994) celebrated numerous national and international triumphs from the mid-1920s, including the popular competition Quer durch Wien (Across Vienna) and the first Maccabiah Games in Tel Aviv in 1932 and 1935, where the Austrian delegation was one of the strongest teams, not least thanks to the swimmers coached by master trainer Zsigo Wertheimer. Swimming stars like Bienenfeld and Löwy were celebrated in Viennese sports newspapers and illustrated magazines, with the exception of the decidedly German nationalist media, although in all but the Zionist media, the acceptable images of sporting femininity tended to obscure Jewish symbols such as the Star of David (Marschik 2018). Unlike male Jewish athletes and officials, there were hardly any stereotypical or anti-Semitic portrayals of Jewish femininity in the sports media. Much as in the Weimar Republic, the successful and—in men’s eyes—attractive swimmers also became objects of advertising messages that played with the image of seductive Jewish femininity.

Boycott of the 1936 Olympic Games

In retrospect, it was probably one specific event that made the Viennese Hakoah swimmers into enduring icons of Jewish sports. When the Austrian sports authorities, after much hesitation, decided to participate in the 1936 Olympic Games in Nazi Germany and nominated a number of Jewish athletes for the Summer Games in Berlin, the three top swimmers—Judith Deutsch (1918-2004), Lucie Goldner (1918-2000), and Ruth Langer (1921-1999)—among others, refused to participate. Even before that, the Maccabean World Federation had called for a boycott of the Games, which was also supported by the Jewish Gymnastics and Sports Federation in Austria. In June 1936, Deutsch wrote to the Austrian swimming federation: “As a Jew I am unable to participate in the Olympic Games in Berlin since my conscience prohibits this. … How serious I am with this decision, you can appreciate by the fact that I am very well aware that I thus forgo the highest athletic distinction, that is, to be allowed to start at the Olympic Games in the Austrian team. I ask you to meet my point of view with understanding and not to subject me to any moral constraints” (Propp 2009, 89).

In fact, Deutsch and her two comrades-in-arms Goldner and Langer were suspended for two years by the Austrian Sports and Gymnastics Front for not appearing in Berlin. The Austrian Swimming Federation, in which officials from the anti-Semitic and Nazi-dominated swimming club EWASK—a fierce rival of Hakoah—played a prominent role, demanded even more severe punishments. In retrospect, Deutsch described her decision, which was difficult for her as an athlete, as follows: “It seemed impossible to me to participate in Hitler’s Germany and to swim in swimming pools where signs marked ‘Dogs and Jews not allowed!’ were only removed for the time of the Olympics” (Bunzl 1987, 117). It was not until 1995 that the Austrian Swimming Federation and the President of the Austrian National Council Heinz Fischer would apologize for the treatment the three athletes had received at that time.

While questions of “Jewish difference” and anti-Semitic confrontations were already widespread in Austrian sports after 1918, these conflicts intensified by the time the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933. Jewish converts and “assimilants” were harshly criticized by the Zionist sports movement, whose political representatives had gained a majority in the IKG in 1932. In his Encyclopedia of Jewish Athletes in Vienna, written after his flight from Austria, longtime Hakoah president Ignaz Hermann Körner (1881-1944), for example, called Antonie Graf a “champion and leader of Viennese women’s sports” but also a “great enemy of Jewish sports.” On the other hand, there were female athletes who were sometimes considered to be Jewish by Jewish National media, but who had denied this family background, including figure skater Fritzi Burger (1910-1999), a medalist in the 1928 and 1932 Olympics, and fencer Ellen Müller-Preis (1912-2007), who won gold in the 1932 Olympics and bronze in 1936 and 1948 and is still listed as a Jewish athlete in many publications despite biographical evidence to the contrary.

Sports as a Lifesaver and the Attempt at a New Beginning after 1945

With the Anschluss in 1938, the dissolution of Jewish sports clubs, and the persecution and murder of the Jewish population, Jewish sports in Austria came to a brutal end. For many Jewish athletes, however, the networks of sports became a life-saving escape route. The lawyer and leading official of the Hakoah swimming club Valentin Rosenfeld, who had emigrated to England, succeeded in enabling numerous female swimmers to leave Vienna. After the expulsion and the Shoah, the Jewish population of Austria was reduced from about 200,000 to just a few thousand in the decades after 1945. Even though S.C. Hakoah was quickly re-established in Vienna, it was not possible to continue the tradition of top Jewish sports in the long term. In the political climate of the Second Republic, which was defined by Austria’s assertion of victimhood under the Nazis, the Jewish community, whose fate contradicted this assertion, had to direct its cultural activities mainly inwards for a long time (Bunzl 2000, 234). Jewish women continued to be active in Austrian sports, but only rarely did they become publicly visible as such. One of the few exceptions was the journalist and sports official Alice (Kalischer-)Kaufmann (1919-2002). As a young woman, Kaufmann had been active in the Socialist Workers’ Youth and a handball and soccer player. She fled persecution in Austria and survived as a member of the Resistance in France, then returned to Vienna and worked as a sports journalist and handball official. In the 1950s, Kaufmann became the first female head of a newspaper sports editorial office, and her life partnership with a prominent Austrian female athlete also meant that she crossed the sexual boundaries of her time.

It was only in the 1990s that Jewish sports experienced a new upswing in Austria. In a changed social environment, in which Jewish life was now considered normal and enriching, sports in particular offered an important stage for “rendering Jews culturally visible.” Clubs like S.C. Hakoah or the soccer club Maccabi “occupy a unique conceptual position . . . that figures present-day Jewish sports both as the continuation of a glorious Austrian-Jewish athletic tradition and the signpost of a positively diversified and newly growing Jewish community” (Bunzl 2000, 240). In 2011, Vienna served as the venue for the European Maccabi Games for the first time.

We are grateful to Agnes Meisinger and Matthias Marschik for their helpful comments, and to Jason Heilman for editing the English version.

Bakondy, Vida. Montagen der Vergangenheit. Flucht, Exil und Holocaust in den Fotoalben der Wiener Hakoah-Schwimmerin Fritzy Löwy. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2017.

Betz, Susanne, Monika Löscher, and Pia Schölnberger, eds. „… mehr als ein Sportverein.“ 100 Jahre Hakoah Wien 1909-2009. Innsbruck, Vienna, Bozen: StudienVerlag, 2009.

Brenner, Michael, and Gideon Reuveni, eds. Emancipation through Muscles: Jews and Sports in Europe. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

Bowman, William D. “Hakoah Vienna and the International Nature of Interwar Austrian Sports.” Central European History 44, no. 4 (2011): 642–668.

Bunzl, John, ed. Hoppauf Hakoah. Jüdischer Sport in Österreich. Von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart. Vienna: Junius, 1987.

Bunzl, Matti. “Resistive Play. Sports and the Emergence of Jewish Visibility in Contemporary Vienna.” Journal of Sport & Social Issues 24, no. 3 (August 2000): 232–250.

Centropa. “Edith Brickell (2002).” Accessed December 21, 2020. https://www.centropa.org/de/biography/edith-brickell#Meine%20Kindheit.

Centropa. “Erika Rosenkranz (2003).” Accessed December 21, 2020. https://www.centropa.org/de/biography/erika-rosenkranz#Meine%20Kindheit.

Donath, Hedwig. “Aus den Gesprächen unserer Turngeräte. ‘Das neue Pferd’.” Jüdische Turnzeitung 7, no. 7 (1906): 120–123.

Donath, Hedwig. “Skizze.” Jüdische Turnzeitung 10, no. 10/11 (1909): 209–212.

Egger, Sarah. Die Muskeljüdin? Frauen in jüdischen Sportvereinen von 1900 bis 1912 im Umgang mit dem männlich geprägten Ideal des Muskeljudentums, MA thesis. University of Vienna, 2017.

Feuchtner, Carmen. “‘Rekord kostet Anmut, meine Damen!’ Zur Körper-Kultur der Frau im Bürgertum Wiens (1880-1930).” Tel Aviver Jahrbuch für deutsche Geschichte 21 (1992): 127–151.

Graf, Antonie. “Die Frau im Sport.” Wiener Hausfrauen-Zeitung, 11 February 1912, 67

Günther, Dagmar. Alpine Quergänge. Kulturgeschichte des bürgerlichen Alpinismus (1870-1930). Frankfurt/Main, New York: Campus, 1998.

Hachleitner, Bernhard, Matthias Marschik, and Georg Spitaler, eds. Sportfunktionäre und jüdische Differenz. Zwischen Anerkennung und Antisemitismus – Wien 1918 bis 1938. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2019.

Hartwich, Emmy. “Die Frau in den Bergen. Eine heitere Plauderei über ernste Dinge.” Mitteilungen des Deutschen und Oesterreichischen Alpenvereins 50, no. 3 (1924): 26–28.

Herschmann, Otto. Wiener Sport (Großstadt-Dokumente vol. 12), Berlin, Leipzig: Hermann Seemann Nachfolger, 1904.

Körner, Ignaz Hermann. Lexikon jüdischer Sportler in Wien. 1900–1938. Ed. Marcus G. Patka im Auftrag des Jüdischen Museums Wien. Vienna: Mandelbaum, 2008.

Leo Baeck Institute – New York. “AHC interview with Greta Stanton (1998).” Accessed December 21, 2020. https://links.cjh.org/primo/lbi/CJH_ALEPH000193069, Side A, 00:28:30-00:29:05, Side B 00:03:32-00:08:03.

Leo Baeck Institute – New York. “AHC interview with Nelly Sommer-Anderson (1999).” Accessed December 21, 2020. https://links.cjh.org/primo/lbi/CJH_ALEPH000193074, Side A 00:25:14-00:27:25.

Leo Baeck Institute – New York. “AHC Interview with Erika Benis (2003).” Accessed December 21, 2020. https://links.cjh.org/primo/lbi/CJH_ALEPH000193162.

Leo Baeck Institute – New York. “AHC interview with Augusta Appel (2008).” Accessed December 21, 2020. https://links.cjh.org/primo/lbi/CJH_ALEPH000370617, 00:13:40-00:18:23.

Leo Baeck Institute – New York. “AHC interview with Gerty Graber (2008).” Accessed December 21, 2020. https://links.cjh.org/primo/lbi/CJH_ALEPH000370624.

Leo Baeck Institute – New York. “AHC interview with Edith Himmel (2008).” Accessed December 21, 2020. https://links.cjh.org/primo/lbi/CJH_ALEPH000359195, 12-13.

Loewy, Hanno, and Gerhard Milchram, eds. Hast du meine Alpen gesehen? Eine jüdische Beziehungsgeschichte. Herausgegeben für das Jüdische Museum Hohenems und das Jüdische Museum Wien. Hohenems: Bucher, 2009.

Marschik, Matthias. “Von jüdischen Vereinen und ‘Judenklubs’. Organisiertes Sportleben um die Jahrhundertwende.” In: Evelyn Adunka, Gerald Lamprecht, and Georg Traska (eds.): Jüdisches Vereinswesen in Österreich im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, 225–244. Innsbruck, Vienna, Bozen: StudienVerlag, 2011.

Marschik, Matthias. “Depicting Hakoah. Images of a Zionist Sports Club in Interwar Vienna.” Historical Social Research 43, no. 2 (2018): 129–147.

Mayreder, Rosa. “Die Dame.” Die Zukunft, 21 September 1901, 496–504.

Meisinger, Agnes. 150 Jahre Eiszeit. Die große Geschichte des Wiener Eislauf-Vereins. Herausgegeben vom Wiener Eislauf-Verein, Vienna, Cologne, Weimar: Böhlau, 2017.

Pass Freidenreich, Harriet. Jewish Politics in Vienna, 1918-1938. Bloomington, Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991.

Pfister, Gertrud. “Die Anfänge des Frauenturnens und Frauensports in Österreich.” In Turnen und Sport in der Geschichte Österreichs, edited by Ernst Bruckmüller and Hannes Strohmeyer, 86–104, Vienna: ÖBV Pädagogischer Verlag, 1998.

Presner, Todd Samuel. Muscular Judaism. The Jewish body and the politics of regeneration. Abington, New York: Routledge, 2007.

Propp, Karen. “The Danube Maidens. Hakoah Vienna Girls’ Swim Team in the 1920s and 1930s.” In Susanne Helene Betz, Monika Löscher, and Pia Schölnberger, eds. “… mehr als ein Sportverein”. 100 Jahre Hakoah Wien 1909-2009, 81–93.

Rozenblit, Marsha L. The Jews of Vienna, 1867-1914. Assimilation and Identity. New York: The State University of New York Press, 1983.

Schweighofer, Astrid. Religiöse Sucher in der Moderne. Konversionen vom Judentum zum Protestantismus in Wien um 1900. Berlin, Munich, Boston: De Gruyter, 2015.

Silverman, Lisa. Becoming Austrians. Jews and Culture between the World Wars. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Spiegel, Else. “Abrüsten!” Dokumente der Frauen, no. 21, March 15, 1900, 725–727.

Wildmann, Daniel. Der veränderbare Körper. Jüdische Turner, Männlichkeit und das Wiedergewinnen von Geschichte in Deutschland um 1900. London, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2009.

Zilberman, Yaron, dir. Watermarks. The Jewish swimming champions who defied Hitler. Israel, 2004.