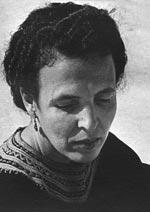

Sylvia Blagman Syms

Photograph by William Gottlieb, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress.

Gifted jazz saloon singer Sylvia Blagman Syms was praised by Billie Holliday, Frank Sinatra, and Duke Ellington. Syms spent her teenage years sneaking into saloons to listen to jazz musicians and by her mid-twenties was performing in clubs herself. In 1949, she was discovered by Mae West, who became her mentor and began performing on stage, film, and television. Success came with her 1956 recording of “I Could Have Danced All Night,” which sold more than a million copies, and she went on to record fifteen albums, including one directed by Frank Sinatra. Despite emphysema and lung cancer, she continued to perform in nightclubs and theaters until she died of a heart attack while receiving a standing ovation at the Algonquin Hotel in New York.

Article

“When you perform, it’s a one-to-one love affair with the people out there. That’s how it has to be,” stated Sylvia Syms before her death in 1992. Syms’s dynamic saloon performances were characterized by an intimate storytelling style and a grainy contralto voice combined with honesty, a “been-there” aura, and a genuine love of the connection with her audience. She was touted as one of the best contributors to her genre by such noteworthy peers as Cy Coleman, Billie Holiday, Frank Sinatra, and Duke Ellington.

The eldest of three children, Syms was born on December 2, 1917, in New York City to a poor Russian immigrant father, Abraham Solomon Blagman, and a New York-born, devoutly Jewish mother, Pauline (Weiss) Blagman. Both parents had minimal formal education, and Syms’s own was limited.

Syms nursed her growing musical passion by sneaking out to stand in saloon coatrooms when she was underage to listen to jazz greats such as Mildred Bailey, Billie Holiday, Art Tatum, and Lester Young. Fifty-second (“Swing”) Street became Syms’s musical “classroom.” By the mid-1940s, she was appearing regularly in several clubs and had recorded her first single, “I’m in the Mood for Love.” Syms married Bret Morrison in 1946 and divorced in 1953 due to differences in lifestyles and goals.

In 1949, she was discovered by Mae West, who became a significant teacher and influence on Syms’s performing style. Syms participated in musical theater throughout much of her career, appearing in Diamond Liz, South Pacific, Camino Real (her favorite role), and Hello, Dolly!

In 1956, she recorded her major hit, a double-tempo version of “I Could Have Danced All Night,” which sold more than one million copies. Also, in the mid-1950s, she married dancer Ed Begley, whom she also later divorced. She had no children. Although her health began to fail from emphysema and lung cancer in the 1960s, she continued to perform both in clubs and musical theater.

In the 1980s, Syms taught master classes on musical theater singing at Northwood Institute in Dallas, Texas. Considering herself a historian, she enjoyed passing on her musical knowledge, especially that of 52nd Street. She was indeed a living monument to an era of New York music; her nightclub career spanned fifty-one years.

Syms recorded fifteen albums. Successful songs included “In Times Like These,” “Dancing Chandelier,” and “It’s Good to be Alive.” She toured the United States and eventually performed throughout the world.

Syms was a dynamic personality with a sharp, analytical eye. She was barely five feet tall and was perennially plump, giving her a distinctive, round face that prompted loving nicknames such as “Buddha” (Sinatra) and “Moonbeam Moscowitz” (Tatum). Her presence was said to be immediately commanding and a joy to behold.

Judaism was not an active part of Syms’s life; as she said in 1974, “her religion [was] people.” Singing became a “total cleansing” for Syms, which helped her feel young and full of life. She did show respect for her mother’s Jewish faith, however, by giving generously to her mother’s synagogue.

Syms died of a heart attack on May 10, 1992, while receiving a standing ovation after a performance at the Algonquin Hotel in New York City.

Selected Discography

After Dark, Version VLP 1D3 (1954).

The Fabulous Sylvia Syms, 20th Century-Fox TFS 4123 (1964).

A Jazz Portrait of Johnny Mercer, DRG Records, AHB-3281 (live 1984, 1995).

Lovingly, Atlantic SD 18177 (1976).

Sings, Atlantic 1243, and Decca DL 8188 (1956).

Songs of Love, Decca DL 8639 (1958).

Sylvia Is ..., Prestige 7439 (1966).

Then Along Came Bill, DRG Records, ocm23234338 (1990).

Torch Songs, Columbia CS 8243 (1961).

You Must Believe in Spring, ELBA 5004.

Bailey, Muriel (née Blagman). Telephone conversation with author, May 5, 1996.

Balliet, Whitney. American Singers (1988).

Biography Index. Vols. 10–12.

Blagman, Burton. Telephone conversation with author, May 6, 1996.

“Died, Sylvia Syms.” Time (May 25, 1992): 23.

Gavin, James. Intimate Nights: The Golden Age of New York Cabaret (1991), and “Sylvia Syms, One of Pop’s Greatest Storytellers.” NYTimes, May 17, 1992, 29.

Holden, Stephen. “Our Perennial Songbirds.” NYTimes Magazine, November 15, 1987, 47–48, and “Sylvia Syms, Singer, Dead at 74.

Cabaret Artist with Saloon Style.” NYTimes, May 11, 1992, D10.

Koenig, Rhoda. “Nightlife: Fall Preview.” New York (September 18, 1978): 56–57.

Palmer, Robert. “The Women of Jazz: Where They Are Singing.” NYTimes, November 5, 1982, 12.

Wilson, John S. “Sylvia Syms, Singer from Swing Street.” NYTimes, August 10, 1979, 21.

![blue.jpg - still image [media] blue.jpg - still image [media]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/mediaobjects/blue.jpg?itok=RkdKmpf6)