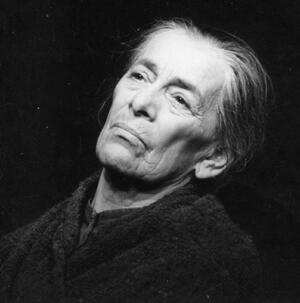

Helene Weigel

Helene Weigel was a respected matriarch of nineteenth-entury theater, known for her maternal roles in Bertolt Brecht plays and as the director of the Berliner Ensemble theater in East Germany. Born in Vienna in 1900, Weigel moved to Berlin to perform in 1922, where she met and married Brecht. Together they had two children, and Weigel made a conscious effort to distance herself from her Jewish heritage. In 1933, they fled Germany and traveled to European countries and America, before settling in East Germany. Weigel’s distinctive acting style consisted of a subtle combination of realistic and stylized dialogue. Brecht and Weigel were communists. Weigel was also known for her philanthropy, giving generously to many charities throughout her life--although this activity went against official socialist doctrine, which claimed that such aid was unnecessary in the classless, “egalitarian” society.

Known in particular for her maternal roles in such Bertolt Brecht plays as The Mother and Mother Courage, Helene Weigel was also a respected matriarch off the stage as director of the Berliner Ensemble theater in East Germany, and beloved mother to two children who, like others close to Weigel, called her by the affectionate nickname “Helli.”

Early Life and Family

Weigel was born on May 12, 1900, to an upper-middle-class Jewish family in Vienna. Her sister, Stella, was born in 1894 and died in 1934. Her father, Siegfried Weigl (1869–1941), was an accountant general in a textile factory, and her mother, Leopoldine Pollak Weigl (1867–Vienna 1927), was a toy-store proprietor. Helene Weigel attended the controversial progressive school founded by social reformer Eugenie Schwarzwald, where expressionist artist Oskar Kokoschka (1886–1980) taught drawing. Weigel began taking acting lessons in 1917 against her parents’ will, eventually obtaining engagements with the New Theater in Frankfurt am Main (1919–1921) and with the Frankfurt Playhouse (1921–1922). In June 1922 Weigel moved to Berlin, where for the next decade she acted in numerous plays, including some by such prominent contemporary playwrights as Marieluise Fleisser (1901–1974), Ernst Toller (1893–1939), and Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956).

On April 10, 1929, Weigel married Brecht, the father of her child Stefan, who was born in 1924 (died 2009). Distancing herself and her son from their Jewish heritage, Weigel declared their official resignation from the Jewish Community in Berlin on September 26, 1928. In 1930 Brecht and Weigel had another child, Barbara, who later noted that her mother’s Jewish heritage was not a topic discussed at home, although dozens of Weigel’s relatives were killed in Auschwitz and her father was deported to the Łódź ghetto in 1941. (Barbara Brecht-Schall lived in Berlin until her death in 2015.)

World War II

On February 28, 1933, a day after the burning of Berlin’s parliament building, Weigel and her family fled to Prague. Via Vienna and Switzerland, they arrived in Denmark in June, where they soon bought a house on the Danish island Fünen. There was little opportunity for Weigel to work in Denmark, but in 1937 she traveled with a group of German exiles to Paris and played the title mother figure in Brecht’s Señora Carrar’s Rifles. In the following year, the same group performed scenes from Brecht’s Fear and Misery of the Third Reich, including “The Jewish Wife” played by Weigel.

The German citizenship of Weigel and her children was revoked in June 1937, two years after Brecht’s was officially invalidated. The family moved to Sweden in 1939, then to Finland the following year, finally reaching California in 1941, where they remained until 1947. Weigel experienced a forced hiatus from acting during this time, expending most of her energy raising her two children and ensuring that Brecht could continue with his work, even learning how to bind his manuscripts herself. Nevertheless, she persisted with regular voice and body exercises to keep her limber for future acting engagements.

After a short stay in Zurich, Weigel and Brecht moved back to Germany and settled in the Soviet sector of Berlin, where they immediately proceeded with their theater work. The January 1949 premiere of Mother Courage in Berlin quickly turned Weigel into the city’s best-known actress. Later that same year, the Berliner Ensemble was founded, beginning its successful run with director Weigel taking the lead in administrative as well as stage roles. She was also active in costume design, a talent enhanced by her interest in art history.

Acting Career and Political Views

Weigel’s distinctive acting style consisted of a subtle combination of realistic and stylized dialogue and gestures, resulting in her own interpretation of the “alienation effect” promoted by Brecht. Her famous “mute scream” in Mother Courage, a move inspired by a photograph of a mother mourning her child’s death after a Japanese attack on Singapore, exemplified this style. Influenced in part by Chinese theater, Weigel’s movements on stage were employed deliberately and economically, as the actress believed that too many details would lead to an extreme naturalism that could ruin a character.

Like Brecht, Weigel was a committed Communist who joined the Communist Party in Berlin in 1930. Though she had reservations about the East German totalitarian system, she did nothing that might jeopardize her work as director of the Berliner Ensemble and her challenging mission of publishing Brecht’s complete works and setting up his archives after his death in 1956. However, she occasionally protested injustices, such as the arrest of young philosopher Wolfgang Harich in 1957. Otherwise, her activist efforts were devoted to such issues as the below-par children’s shoe industry in East Germany, as well as the country’s lack of bottled baby food. Weigel was also known for her philanthropy, giving generously to orphanages and other charities—although this activity went against official socialist doctrine, which claimed that such aid was unnecessary in the classless, “egalitarian” society.

In both her personal and professional life Weigel was known for her strength, energy, diplomacy, and good humor. Friends praised her warmth in regularly welcoming people into her home, even in her temporary quarters in Denmark and Sweden. While still in California she sent countless care packages to starving artists and others in Europe after the war. Weigel’s open-door policy with the actors at the Berliner Ensemble complemented her readiness to help new Ensemble members in finding housing, not always an easy task in East Germany. Ensemble meetings took place not only in her office but also at her home, where she often cooked for the theater employees.

Legacy

Weigel’s characteristic modesty is exemplified in her claim that she did not give interviews as a rule because they were only for stars, and through Brecht’s observation that “never did she set out to show her own greatness, but always the greatness of those whom she portrayed” (Helene Weigel: Actress. A Book of Photographs, p. 54). Faced with such challenges as an exile, an openly unfaithful husband, and the surveillance of first the FBI in America and later the East German secret police, Weigel is said to have retained her sense of humor. On a particularly cold day in California, for instance, she reportedly invited an undercover FBI agent inside where he could observe her more easily.

Weigel died on May 6, 1971, about a month after breaking ribs on stage in Paris as she played Pelagea Vlassova in The Mother one last time. She was buried beside Brecht at the cemetery on Chaussee Street in Berlin, next to the house into which she had moved in 1953, where the Brecht-Weigel archives are still located.

Selected Theater Roles (Premiere Performances)

September 1919: Marie in Georg Büchner’s Woyzek

November 1920: Old woman in Georg Kaiser’s Gas II

September 1921: Meroe in Heinrich von Kleist’s Penthesilea

December 1922: Hedwig in Gerhart Hauptmann’s Hannele

December 1925: Klara in Friedrich Hebbel’s Maria Magdalena

April 1926: Clementine in Marieluise Fleisser’s Purgatory in Ingolstadt

March 1927: Leokadia Begbick in Bertolt Brecht’s Man Equals Man

November 1927: Grete in Ernst Toller’s Hinkemann

May 1929: Constance in Shakespeare’s King John

December 1930: Agitator in Bertolt Brecht’s The Measures Taken

January 1932: Pelagea Vlassova in Bertolt Brecht’s The Mother

October 1937: Teresa Carrar in Bertolt Brecht’s Senora Carrar’s Rifles

May 1938: Judith Keith in Bertolt Brecht’s The Jewish Wife

February 1948: Antigone in Brecht’s version of Sophocles’ Antigone

January 1949: Anna Fierling in Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage

May 1953: Frau Großmann in Erwin Strittmatter’s Katzgraben

October 1954: Natella Abaschwili and Mother Grusinien in Bertolt Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle

May 1961: Martha Flinz in Helmut Baierl’s Frau Flinz

May 1965: Volumnia in Bertolt Brecht’s Coriolan

June 1968: Frau Luckerniddle in Bertolt Brecht’s Saint Joan of the Stockyards

“Backstage with the Berliner Ensemble.” New

Theater Magazine 6.3 (1966): 15–23.

A conversation with Helene Weigel and others in the Berliner Ensemble, in

which Weigel declares that she does not give interviews: “Interviews are for

stars—I am not a star and so I never give interviews. If any questions on

our work are to be answered, they must be answered by the Ensemble as a whole—this

is because the whole company discuss a production and contribute to it” (15).

Chausseestrasse

125. Die Wohnungen von Bertolt Brecht und Helene Weigel in Berlin

Mitte.

Berlin: Stiftung Archiv der Akademie der Künste, 2000.

Documents Weigel and Brecht’s living and working quarters on Chaussee Street

through pictures and texts by friends and acquaintances. Photographs by Sibylle

Bergemann.

Hecht, Werner. Helene

Weigel. Eine große Frau des 20. Jahrhunderts. Frankfurt am Main: 2000.

Hecht is a renowned scholar of Brecht and Weigel. This book includes a chronicle

of Weigel’s career and many photographs of Weigel in her various personal

and professional roles.

Kebir, Sabine. Abstieg

in den Ruhm. Helene Weigel. Eine Biographie. Berlin: 2000.

A comprehensive biography of Helene Weigel in narrative form.

Pintzka,

Wolfgang, ed. Helene

Weigel, Actress. A Book of Photographs.

Trans. John Berger and Anna Bostock. Berlin:

1959.

Includes

texts dedicated to Helene Weigel by Bertolt Brecht, and photographs by

Gerda

Goedhart.

Stern, Carola. Männer

lieben anders. Helene Weigel und Bertolt Brecht. Berlin: Rowohlt, 2000.

Details the at times tumultuous personal and working relationship between

Weigel and Brecht. Also includes a four-page chronology of Weigel’s life.

Wilke, Judith, ed. Helene

Weigel 100. The Brecht Yearbook 25. Madison, WI: 2000. 75–94.

A special edition of the Brecht

Yearbook commemorating the hundredth anniversary of Helene Weigel’s

birthday, with valuable contributions from various scholars covering different

aspects of Weigel’s life and work.