Women in Israeli Music

Jewish women have contributed significantly to musical performance and other music-related fields, practices, and institutions in pre- and post-state Israel. The arrival of Jewish immigrants from Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa, from the end of the nineteenth century until as late as the 1980s, resulted in a culturally diverse proliferation of music in the Israeli context, much of which involved performance and composition by Jewish women. Jewish women in Israel have also contributed significantly to the development of music education and music scholarship, being actively involved in music studies publications and projects as well as in the development of music education institutions.

Since the time of the Jewish community in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel. "Old Yishuv" refers to the Jewish community prior to 1882; "New Yishuv" to that following 1882.Yishuv, Jewish women have made significant contributions to Israeli music composition, performance, and production. In pre-State Israel and in the early years of the state, women’s contributions to Israeli music could be categorized according to the national and cultural origins of women arriving as immigrants from Europe, whose experiences were often shaped by the wars, persecution, and ideologies of the first half of the twentieth century. From the 1950s until the 1980s, an influx of Jewish women from Middle Eastern and North African regions arrived, who had fled their birthplaces due to the rise of Arab nationalism during the instability of the post-colonial period. The arrival of these immigrants and their diverse European and Middle Eastern Jewish cultures resulted in many new social and musical encounters in Israel and coalesced into a mosaic of musical practices united under a common Jewish identity. During this period, Jewish groups practiced traditional ethnic folk musics from the Diaspora in a variety of song-types and languages in the new Israeli context (i.e. Yiddish and Russian folk songs; Ladino romanceros and ballads, Yemenite songs). Although the musical sphere in Israel (as in other areas of cultural production) was and continues to be a male-dominated environment, since the 1880s Jewish women have contributed significantly to musical performance and other music-related fields, practices, and institutions.

Folk Music

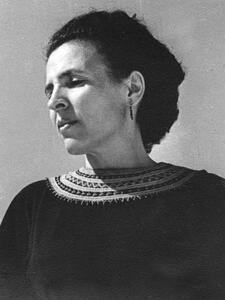

Brachah Zefira in the 1930s.

From Wikimedia Commons.

During pre- and post-state waves of aliyot, or Jewish immigration, folk music had a special function, helping newcomers to Israel deal with the hardships of immigration and building new lives. However, Zionist ideology encouraged Jewish unification centered on shared values, which led to the transformation of folk songs into a Hebrew-language medium. These translated folk songs were performed by many women artists, including Esther Gamlielit (1919-2012), who performed Yemenite folk songs in Hebrew, and Brachah Zefira (1910-1990), whodrew inspiration from the Yemenite melodies with which she had grown up, transforming them into a new musical idiom. Other female singers of Yemenite music in this tradition included Shoshana Damari (1923-2006), who arrived in Israel from Yemen in 1924 and achieved success as a performer at a young age. Later generations of such performers included Na’ama Nardi (1932-1989), Brachah Zefira’s daughter. While women from other communities also performed folk songs in the early period, they largely remain unknown and undocumented.

Shirei Eretz Yisrael (Songs of the Land of Israel)

Before the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, many European folk songs imported by Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe were transformed into a canon of nationalist songs reflecting love for the country and pioneering. This song collection, dubbed “Songs of the Land of Israel” (“Shirei Eretz Yisrael”), is understood as a sub-category of the general term “Hebrew Song,” which designates songs with Hebrew-language texts (excluding liturgical and para-liturgical Hebrew songs). Songs of the Land of Israel continue to be performed today in a variety of forms.

Songs of the Land of Israel were often the creations of distinguished poets and composers and often supported by agencies such as the Jewish National Fund (Shahar 1993). The lyrics drew on literary tropes to evoke specific places in the Israeli landscape, using simple melodies and accompaniment, which facilitated their use in group-singing contexts. Important women composers of this genre include Nira Hen (1924-2006), who was born at Kibbutz Ein Harod and who composed many songs and operas for children, and Sara Levi-Tanai (1910-2005), who composed “Kol Dodi” (“my beloved”) and “El Ginot Egoz” (“to the nut trees”). Naomi Shemer (1930-2004) is considered one of the most important and prolific composers and performers of the Songs of the Land of Israel. She authored and released hits such as “Yerushalayim Shel Zahav” (“Jerusalem of Gold,” 1967), which became a second Israeli national anthem in the aftermath of the Six Day War, and “Lu Yehi” (1973), which also achieved iconic significance and catapulted its performer, folk singer Chava Alberstein (b.1946), to national fame. “Lu Yehi” paid homage to the Beatles’ “Let it Be” (1970) and promoted solidarity among Jewish Israelis during the Yom Kippur War of 1973. Nurit Hirsch (b.1942) studied at the Music Academy in Tel Aviv and composed many pieces in the Songs of the Land of Israel repertoire. Her most popular notable song is “Bashanah Haba’ah” (“Next Year,” 1970); she composed the music and songwriter Ehud Manor composed the lyrics.

Mizrahi Music

Image of singer Ofra Haza from a mid-1990s Israeli television broadcast. Cropped from a larger image at Wikimedia Commons.

Muzika Mizrahit (“Lit. "Eastern." Jew from Arab or Muslim country.Mizrahi music”) is a label used to denote all musical output of Jewish immigrants from the Arab world. The music was originally considered controversial because of its origins and proximity to Christian or Muslim Arab culture. However, Mizrahi music is now part of mainstream Israeli music, owing to changing performance practices and musical fusion. Indeed, it has become part of a broader global process of musical change.

Stylistically speaking, Mizrahi music is a deliberate blend of both “eastern” and ”western” elements, with varied uses of maqmat (Middle Eastern modes). The term Muzika Yam Tikhonit (Mediterranean music) is often associated with Muzika Mizrahit, but the former usually describes a Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardic and/or Ladino influence (Sheleg 2014, 124). In the 1960s, performers added acoustic guitar and electric guitar to ensembles made up of more traditional instruments, such as the oud and the darbukkah. This inclusion caused a rapprochement with other emergent musical genres (e.g. rock). Mizrahi music’s origins in Israel can be traced to grassroots performers, most notably from Kerem Hatemanim, the mainly Yemenite neighborhood of Tel Aviv. Initially, lyrics were texts taken from classic Hebrew literature, such as texts and poems by medieval Hebrew poets.

A pioneer of Mizrahi music, Ofra Haza (1957-2000) achieved iconic significance. Also worthy of mention is Ahuva Ozeri (1948-2016), who was of Yemenite origin and described by the Times of Israel as a “pioneer of Israeli music.” Zehava Ben (b. 1968), born Zehava Benvenisti, is a singer of Moroccan ethnic origin. Born in Beersheba, she started out recording little-known independent albums and gradually rose to national success. Much of Ben’s music defied conventional categories of identity, since she openly embraced her Arab Jewish heritage (Horowitz 2010). There are currently many acclaimed women performers of Mizrahi music, such as Sarit Hadad (b. 1978), whose parents hail from Dagestan in the Caucasus. Hadad’s performance of this music as a person of non-Middle Eastern origins marked a transformation of emphasis from essentialist notions of the performer to characteristics of the music itself, including virtuosity and aesthetics. Hadad is well-known for her iconic song “Shema Yisrael,” but also for performing classics by the classic Egyptian twentieth-century singer Oum Kalthoum (1898-1975). Miri Mesika (b.1978), of Iraqi-Jewish and Tunisian-Jewish ethnic origin, became well-known with her first album Miri Mesika (2004).The popular singing competition show Kochav Nolad (A Star is Born) showcased some new talent in this genre, including artists such as Nasrin Qadri (b. 1986), a virtuosic vocalist who converted to Judaism, and Eden Ben-Zaken (b. 1994), who performs upbeat and youthful songs.

Rock

The rock-and-roll scene in Israel emerged in the 1970s, although “fringe groups” had existed since the mid-1960s (Regev 1992). Israeli rock was initially performed largely by male performers. In the 1980s, when rock became “dominant in the field of popular music in Israel” (Regev 1992, 7), women performers, who had hitherto had only supportive roles, were able to achieve success as main acts. Examples of this phenomenon include Corinne Allal (b. 1955), Astar Shamir (b. 1955), Nurit Galron (b. 1951), and Yehudit Ravitz (b. 1956). One of the leading woman rock musicians in Israel, Ravitz achieved success with her 1984 Springsteen-influenced breakthrough album, Derech Hamshi (“Silk Road”), and Ba’ah Me’Ahava (“Coming from Love”). Dana Berger (b. 1970) came on the rock scene in the 1990s, playing ballads characterized as “soft pop rock.” Ninet Tayeb (b. 1983) is an important indie-rock performer who has had success in Israel as well as in the United States. Tayeb has performed with Orit Shahaf (b. 1971) who, with her partner Tom Petrover, was also part of a husband-wife duo making up the popular hard rock band HaYehudim (“The Jews”), with hits such as Kach Oti (“Take Me,” 1995).

Hip Hop

Hip Hop emerged in Israel in the early 1990s. While Hip Hop in Israel is mostly performed by men, ome notable Hip Hop performers and producers are women. Rinat Gutman (b. 1980) is an Orthodox Jewish rapper and songwriter hailing from Jerusalem. Adi Ulmansky (b. 1989), also a Jerusalem-born Hip Hop artist, released her debut album “Shit just got real” in 2013. The newest female talent in Israeli Hip Hop is Ethiopian-Israeli artist Eden Dersso (b. 1998), who released hit songs such as “Transparent Crown” (2018), in which she refers to herself as the “New Queen of Sheba” (Ghermezian 2019). Three sisters, Tair, Liron and Tagel Haim, form the pop/Hip Hop group AW-A (founded in 2015); they emphasize traditional aspects of Yemenite culture combined with progressive politics that challenge gender stereotypes, with a stunning visual aesthetic in their music videos.

Jazz

Jazz performance has existed since the times of the Mandate for Palestine given to Great Britain by the League of Nations in April 1920 to administer Palestine and establish a national home for the Jewish people. It was terminated with the establishment of the State of Israel on May 14, 1948.British Mandate (1918-1948), though it only became a significant genre in the 1990s. Women performers include Edna Goren (b. 1945), a jazz singer of Yemenite origin who has been dubbed “the first lady of Israeli jazz,” Liz Magnes (b.1943) (piano), and Iris Portugal (b.1966) (percussion and voice). More recently, Anat Cohen (b. 1975), often called “Queen of Clarinet,” is a jazz clarinetist known for her eclectic use of the clarinet register as well as for her sensational improvisational skills. Anat Fort (b. 1970) is a jazz pianist and composer with her own trio who has had success not only in Israel, but also in Europe and North America. In December 2018, she became the first woman to be awarded the Prime Minister Jazz Composers Award (Israel).

Western Art Music

Particularly after Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, many European Jewish immigrant composers and performers sought to establish the Western art music tradition in their new homeland. Consequently, Western art music institutions emerged in Israel in the 1930s, with ensembles and institutions such as music schools in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv and the Palestine Philharmonic Orchestra (established 1936, today the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra). These institutions had both a musical and a national-symbolic function. While newly composed Israeli Western art music could be firmly identified according to European standards, it nevertheless often contained specifically “Israeli” elements and idioms. For instance, the compositions of Paul Ben-Haim (1897-1994) and Aelxander Boskovich (1907-1964) reflected a post-late-Romantic style in the Western Art musical tradition, blended with an emerging “Mediterranean” style that became the prevalent idiom of early Israeli composers of classical music.

There were initially very few women composers of Western art music in Israel, as was also the case in Europe and North America. However, two women composers should be recognized for their work during the 1950s and 60s: Vardina Shlonsky (1905-1990) and Yardena Alotin (1930-1994). Schlonksy hailed from Russia and produced several compositions of international significance. Alotin was born in British Mandate Palestine and trained at the Israel Conservatory of Music in Tel Aviv. Although she struggled in the male-dominated profession during her lifetime, Shlonsky achieved posthumous success as the “first lady of Israeli music” (Seter 2008). The 1980s onwards saw a significant increase in Jewish women Western art music composers in Israel. Notable figures include Betty Olivero (b. 1954), the first woman in Israel to occupy a professorship in composition, and Shulamit Ran (b.1949), who composed such works as “Between Two Worlds: The Dybbuk” (1997). Olivero and Ran were arguably the only women composers to become relatively mainstream, and both have lived outside of Israel for a significant time. Other women composers of note include Chaya Arbel (1921-2007); Noa Blass (1937-2008); Mary Even-Or (1939-1989); Tsippi Fleischer (b. 1946); Chaya Czernowin (b. 1957); and Rachel Galinne (b. 1949). The Israel Women Composers & Performers Forum, founded by the composer Hagar Kadima (b. 1957) in 2000, became an important contact point for women composers and performers of Western art music. In Western art music performance, Astrith Baltsan (b. 1956) and Pnina Saltzman (1922-2006) are probably the best-known concert pianists in Israel. Baltsan is particularly recognized for her interpretations of Mozart and Beethoven. There have also been many important women performers in Israeli orchestras, including violin players such as Miriam Fried (b. 1946), Edna Michell (b. 1939), and Thelma Yellin (1885-1959). Other instrumentalists include Linor Katz (b. 1987, cello), Tamar Narkiss-Melzer (b. 1962, oboe), Dalit Segal (b. 1970, horn) and Michal Mossek (horn), and Avital Handler (b. 1975, tuba). Of notable mention is the all-female Zmora orchestra based at the Ron Shulamit Music Conservatory. Israel also boasts many well-known chamber ensembles, many of which have women performers, such as the Israel Chamber Orchestra and the Israel Camerata.

Opera debuted in the Yishuv in 1922 with a performance of Gounoud’s Faust in Tel Aviv, and Russian-born Mordechai Golinkin founded the first opera company in 1923. While orchestral performers were almost exclusively men, the introduction of opera guaranteed women singers performance opportunities, such as Golinkin’s 1923 production of Verdi’s La Traviata. During the early days of the state, many women emigrated from countries in which they had already been trained in the operatic tradition, such as United States-born Edis de Phillipe (1912-1979), who founded the Israel National Opera company in 1947. Early singers of opera included Edith Boroschek (1898-1976) and Hilda Zadek (1917-2019), who trained at the Palestine Academy of Music in Jerusalem. However, not until the 1980s did opera become widely performed in Israel. Today, there are many important women vocalists in The New Israeli Opera, such as Zehava Gal (b. 1948), Mira Zakai (1942-2019), Karin Shifrin (b. 1979), and Daniella Lugasy (b. 1982).

Everyday Life

Women’s music-making, especially singing, developed in Israel as part of everyday life and quotidian social activities. Civilian offshoots of the army ensembles, such as Zemer Troupes, groups made up of both singers and dancers often performing tributes to Israel, and A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutz ensembles and choirs, included women among their ranks. The socialist principles underlying such initiatives maintained all participants be included, not restricted by age or gender, which guaranteed women’s participation (Perelson 1998, 115). In addition to participation in formal groups, a tradition of women singing for other women developed. It was thought that these songs initially developed to circumvent the traditional prohibition in some Orthodox contexts of a man hearing a woman’s voice, called Kol Isha (“A woman’s voice”). These songs have a broad thematic scope, tending to focus on biblical stories and life-cycle events. They were typically sung in the vernacular and in Modern Hebrew. Today, women continue to play a central role in folk-traditional musical works as composers of popular and artistic music as well as performers and researchers (Shai and Kollender 2008: 277)

Religious Practice

Although traditional Jewish contexts place restrictions on women’s singing, there are areas in which women (traditional and non-traditional) engage in religious song. Notably, there is no prohibition against women singing or praying for other women, resulting in women’s prayer groups or Rosh Chodesh (new month) groups that meet regularly. A well-known trans-denominational group that chose to sing the religious service in public, despite much contention, is Women of the Wall, founded in 1988. The group’s mission is to “attain social and legal recognition of their right as women, to wear prayer shawls, pray, and read from the Torah, collectively and aloud, at the Western Wall” (Sermer 2019). Despite the group’s goals being arguably more political than religious, their activities have nonetheless brought women and women’s performance of musical liturgy to the forefront of Israeli debate. In Israeli Reform contexts, there are a few female cantors. Cantor Tanya Segal (b. 1957) was ordained at the Hebrew Union College in Jerusalem and now practices in Poland. Cantor Tamar Heather Havilio is a full-time cantor operating both in Israel and the United States. Despite not being able to officiate life-cycle events in Israel, she teaches at the Hebrew Union College in Jerusalem.

Music Education

Courtesy of WIZO Archives, Tel Aviv.

A significant number of women have contributed to the development of music education in Israel. Shulamit Ruppin (1878-1912) founded the first music conservatory in Jaffa in 1910 and later founded another in Jerusalem. In 1939, Dr. Helena Kagan, a philanthropist working in the medical profession, founded the Palestine Academy of Music and Art in Jerusalem. Many women direct conservatories and musical organizations throughout the country, such as Esther Narkiss, Daniella Rabinovich (b. 1939), Ofri Broshi, and Adele Deitchman, who runs the Rubin Conservatory in Beersheba. Women have served in other musical education capacities, such as the important but seldom acknowledged Recha Freier (1892-1984), who established many musical programs for youth and adults, including the Israel Composer’s Fund. In this category, one should also acknowledge women leaders in music-related organizations, such as Michal Smoira-Cohn (1926-2015), who headed the international Arthur Rubinstein piano competition and was also a musicologist.

Music Scholarship (Musicology, Ethnomusicology)

Women scholars have made significant contributions to music scholarship in Israel. Professor Edith Gerson-Kiwi (1908-1992), a performer and comparative musicologist, immigrated to Palestine from Germany to escape Nazi persecution. A follower of Robert Lachmann, she is known as one of the founders of musicology in Israel. Gerson-Kiwi developed the first ethnomusicological approach to analyzing the music of Jewish communities in Israel, focusing on “oriental” music. In 1967 the Israel Musicology Society was founded, followed by the establishment of musicology departments in many Israeli universities, most notably the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Israeli women scholars of note in music studies based at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem include Ruth Katz (b. 1927) and Dalia Cohen (1926-2013), who co-authored Palestinian Arab Music (2006) and who were both recipients of the Israeli Prize in music in 2012, and Bathja Bayer (1928-1995), whose research focus was Israeli folksongs. Dr. Ronit Seter is an important researcher in Israeli musicology, specializing in Israeli art music and based at the Jewish Music Research Centre at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Dr. Gila Flam (b. 1956) is a musicologist and librarian who is director of the Music Department and Sound Archives of the National Library of Israel.

Cohen, Dalia and Ruth Katz. Palestinian Arab Music: A Maqam Tradition in Practice. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2006.

Edelman, Marsha Bryan. Discovering Jewish Music. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 2003.

Eliram, T. Bo shir ivri: shirei eretz Yisrael habetim muzikalim vehachavratiyim [Come, you, Hebrew Song: Songs of the Land of Israel, Musical and Social Aspects]. Haifa: University of Haifa, 2006.

Ghermezian, Shiryn. “Eden Dersso is the Changing Face of Israel’s Hip Hop Scene.” Vogueworld. April 2, 2019.

Horowtiz, Amy. Mediterranean Israeli Music and the Politics of the Aesthetic. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010.

Kark, Ruth, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, eds. Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics and Culture. Lebanon, NH: Brandeis University Press, 2008.

Manasseh, Sara. “Women in Music Performances: The Iraqi Jewish Experience in Israel,” PhD Diss, Goldmsiths College, University of London, 1999.

Pendle, Karin, ed. Women and Music: A History. 2nd ed. Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press, 2001.

Perelson, Inbar. “Power relations in the Israeli popular music system,” Popular Music. 17 no. 1 (Jan 1998): 113-128.

Regev, Motti and Edwin Seruossi. Popular Music and National Culture in Israel. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2004.

Regev, Motti. “Israeli rock or a study in the politics of ‘local authenticity,’” Popular Music, 11, no. 1 (Jan 1992): 1-14.

Sermer, Tanya. “Women for, of, and at the Wall: A Performative Analysis of Gender Politics at the Western Wall in Jerusalem.” Women and Music: A Journal of Gender and Culture. 23 (2019): 48-74.

Seter, Ronit “Verdina Shlonsky: ’The First Lady of Israeli Music,’” Min-Ad: Israeli Studies in Musicology Online. Vol. 6, 2007-2008, https://www.biu.ac.il/hu/mu/min-ad/07-08/Seter-SHLONSKY.pdf

Shahar, Natan. “The Eretz Israeli Song and the Jewish National Fund.” In Ezra Mendelsohn, ed. Modern Jews and their Musical Agendas, 78-91. New York: Oxford University Press. Special Issue in Studies in Contemporary Jewry 9.

Shelleg, Assaf. Jewish Contiguities and the Soundtrack of Israeli History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.