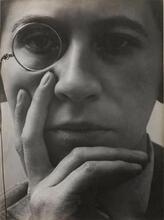

Mariana Yampolsky

One of the most prominent and influential artists of Mexico, Mariana Yampolsky grew up surrounded by intellectual thought, socialist idealism, and an interest in global humanism. In 1952 she immigrated from Chicago to Mexico and became a part of the Taller de Grafica Popular, a cooperative workshop of painters and graphic artists dedicated to social and political ideas. She exhibited her printmaking work in collective exhibitions throughout the world from 1945 to 1958. Yampolsky’s social responsibility and need to communicate the visual messages of artists to the public is seen in her expansive work as a graphic arts editor for school textbooks. Later in her career, she turned to photography and documented the complexity of Mexican culture, including its landscapes, folk art, and poverty.

“I can’t conceive of art without a social context … it’s not just what you as an individual want to express; it must be understandable by others.” (Goldman 187)

Early Life and Family

One of the most prominent and influential artists of Mexico, Mariana Yampolsky was born on September 6, 1925, in Chicago and raised on her paternal grandfather’s farm in Illinois until completing high school. Her father, Oscar Yampolsky, a sculptor and painter, came from a progressive, multilingual, cosmopolitan but financially uncertain Russian Jewish family that had immigrated to the United States at the turn of the twentieth century because of antisemitic persecution. Her father met the woman who would become Mariana Yampolsky’s mother on a study trip to Europe after he won the Prix de Rome. Mariana’s mother was from an upper middle-class German Jewish family who immigrated to Brazil in the late 1930s to escape the Nazis. Her maternal uncle was Franz Boas (1858–1942), considered to be the father of anthropology in the United States.

As a child and maturing young adult Mariana Yampolsky was surrounded by intellectual thought, socialist idealism, and an interest in what is now termed global humanism. In 1944 she received her Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Chicago. Her father died in the same year and her mother moved to New York. A year later Yampolsky moved to Mexico City, becoming a Mexican citizen in 1954. In 1951 she was a founder-member of the Salón de la Plástica. Immediately upon arriving in Mexico, she became a part of the Taller de Grafica Popular and exhibited her printmaking work in collective exhibitions throughout the world from 1945 to 1958. A cooperative workshop of painters and graphic artists dedicated to social and political ideas, the Taller de Grafica Popular in Mexico City was founded in 1937 by Leopoldo Méndez (1902–1969), Pablo O’Higgins (1904–1983) and Luis Arenal (1909–1985), who attempted to create and maintain an independent space for the collaborative production of lithographs, posters and broadsides for the public. Working with limited resources, they received sporadic support from institutions, popular organizations, state agencies and private collectors often based in the United States. They prided themselves on premodern media, such as prints, that represented the “organic self-expression of campesino culture” (Craven 69). The Taller was one of the first presses to publish anti-Nazi lithographic posters in 1938 and was always associated with anti-fascist sympathizers in Spain, Germany and Mexico. In 1948 the Taller collectively produced a portfolio called Estampas de la revolucion mexicana (Prints of the Mexican Revolution). Yampolsky’s images of the Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata (1879–1919) and his followers of revolutionary male and female soldiers illustrate the backbreaking labor of Mexican peasants/revolutionaries and the need for political revolution to correct social injustices. Yampolsky became the first woman member of the studio’s executive committee.

Artwork and Career

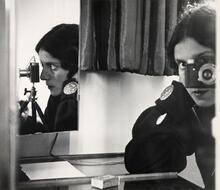

While her first art medium in Mexico was printmaking, in 1948 she turned from engraving to photography. At San Carlos Academy, she studied with Lola Alvarez Bravo (1907–1993), Manuel Alvarez Bravo (1902–2002), the second wife of the noted Mexican photographer who, like her husband, was an exceptional Mexican photographer capturing the haunting duality of daily life in the country, where the past and present exist simultaneously. Lola Alvarez Bravo’s photograph, From Generation to Generation (1950), depicts a mestizo woman with her white-shirted back to the viewer carrying her daughter in her arms. The photographer's mood and purpose are reflected years later in Yampolsky’s photograph Apron (1988). Manuel Alvarez Bravo uncovers a regional pictorial vocabulary in the seemingly quiet, patient timelessness of Mexican/Indian figures. In his photographs there is a poetic sense of death, an anonymity of the people in ordinary activity, and the omnipresent weight of laborious work. Mariana Yampolsky’s immigration to Mexico in 1945 occurred a year before the African American sculptor, Barbara Catlett (b. 1915), moved there. A sense of personal and political exploration, artistic identity and raised social consciousness regarding gender, racial and ethical issues appear as an impetus for these women artists’ full integration into the Mexican cultural vanguard.

The historical division of Pre-Colombian, Christian and post-conquest Mexican art nevertheless has an almost obsessive redundancy in the use of the visual language of cacti, agaves, horses, dogs, serpents, hands at work, clothes lines, drapery folds, masks and skulls reiterating themes of scarcity, death and poverty. It is the pagan/Christian mix in The Blessing of the Corn (1960s) that reveals the insightful socially responsible anthropological vision of Mariana Yampolsky. The thin wood cross with dry corn ears dangles from the tall vertical bar of the cross against a cloudless sky. This wood cross is balanced on top of a wooden shed roof in the lower right hand portion of the photograph. The work is not unlike Manuel Alvarez Bravo’s Crowned with Palms from Chachalacas, Veracruz, 1936, where the long dried palms are scattered on either side of an empty canoe on dry land. The empty canoe can be read as an empty coffin and the palms the remnants of a funerary procession.

Manuel Alvarez Bravo’s Workers of the Tropics from Acapulco, Guerrero, 1944 captures a quotidian activity in a tropical lushness. The seven men in their wide-brimmed straw hats standing near and in the back of a dated truck with a slightly raised windshield framed by enormous yet thinly delineated fronds are agricultural workers waiting for the beginning of their daily labor. In Mariana Yampolsky’s photograph, Maguey House, 1993 the oversized agave plants in the near distance are the building material for the house with the small wooden cross on the seam of its roof where the straw-hatted worker enters his seemingly temporary quarters. The cut agave ledges provide a visual abundance in their repetition so as to build the pyramidal structure. The Bravo and Yampolsky photographs, though divided by a period of more than fifty years, are related in the pride of the indigenismo of the vegetation and rootedness of the people to the land, clarifying the regional vocabulary of Mexican art with its frequent reference to the dignity of agrarian work.

Textbook Illustration and Photography

Mariana Yampolsky’s need to communicate the visual messages of artists to the public is seen in her work as a graphic arts editor for primary school textbooks which used many reproductions of paintings, graphics, sculpture and photography in multidisciplinary school textbooks such as mathematics, literature, the natural and social sciences. Over five years Yampolsky, propelled by social responsibility, assisted in producing five hundred and fifty million books with reproductions of works by the Mexican artists Diego Rivera (1886–1957), Rufino Tamayo (1899–1998) and Pablo O’Higgins, as well as some European masters such as Pablo Picasso. Her boundless energy, her skills as an illustrator, her intellectual acuity and language skills coalesced in the 1960s and 1970s, when she worked as co-editor with Leopoldo Mendez for the book The Ephemera and the Eternal of Mexican Popular Art, as an illustrator for the newspaper El Dia in Mexico City and as an illustrator as well as for Annals, a publication of the Mexican Ministry of Communications. In 1980 Yampolsky was the creator and coordinator of the book Niños (Children), a lavishly illustrated art book on the child’s life cycle in paintings, sculpture, drawings, engravings, and photographs from pre-Hispanic to modern times, published by the Ministry of Public Education. Throughout the 1980s she edited and oversaw the production of art books on Mexican artists, food, toys, customs and ceremonies of Mexico. From the 1970s to the 1990s her photographs were shown in solo exhibitions in the Netherlands, England and Mexico City and in numerous group exhibitions in Mexico City, and she lectured in the United States, Mexico and England.

Yampolsky used her camera to document the activities of the Taller in the 1940s and 1950s. Her major contribution was the perpetuation of the photographic documentation of the complexity of Mexican culture, including its poverty as depicted in the hunger, disease, resignation and lack of sanitation of its people. Yampolsky continued to feel that it is “more important to be authentic than fashionable.” For three years in the late 1960s, she traveled, photographing villages and rural locations for the publishing house of Fondo de la Plástica Mexicana. Her photography documented the Mexican murals throughout the cities and countryside, the work of the nineteenth-century socially critical printmaker Jose Guadaloupe Posada (1851–1913), European painting in Mexico and folk art. The latter can be seen as an expression compensating in part for life’s brutal social and economic inequities. Her photographs intertwine the pervasive inspiration of folk art combined with the dominance of Catholicism and the artifacts and paintings that retell the pious, macabre, revelatory, timeless and redemptive stories of

Christian dogma. For example, her photograph Osario (Ossuary, Dangu, Hidalgo, 1960s) depicts a partially crumbling stone building with a pile of bones and a skull shown in the rectangular opening. A tall slatted wooden door leans behind the curved trunk of the leafless tree that reaches to the large cacti whose roots are eroding the wall of the ossuary. Yampolsky’s photographs present a consciousness of seeing the Mexican landscape and people as undeveloped as well as being “under a type of cultural occupation,” which the art critic Marta Traba noted as being a dilemma in much of Latin America. The cultural occupation can be seen as that of a dominant European aesthetic and Christian spirit. But dovetailing with the longstanding dominance of Western European style was internal political corruption that fostered economic destabilization and an enduring layer of subsistence living. Within the common denominator of poverty, Yampolsky’s images found a distinctive vision to isolate fragments of specific communities as a way to realign the envisioning of global humanism, thus dissipating technological, industrial, social and political hegemonic polarities. Revisiting her uncle Franz Boas’s contention that neither race nor geography, but rather the multidimensional disparate aspects of culture determine human behavior, Mariana Yampolsky provided animated examples of the Mexican people and their artifacts in the photographs The Exterminating Angel (1991); Waiting for the Priest (1987); Orange Stand (1969); Stacked Piñata Pots (1988) and Jailhouse Patio (1987), thus furthering an understanding of the immediate neighbors of the United States.

Yampolsky, who died on May 3, 2002, was survived by her lifelong companion and husband, Arjeh van der Sluis.

American Jewish Year Book. Franz Boas. New York: 1999.

Art Nexus.

The Nexus Between Latin America and the Rest of the World: 1991–2002.

Barnitz, Jacqueline. Twentieth Century Art of Latin America. Austin, Texas: 2001.

Craven, David. Art and Revolution in Latin America 1910–1990, New Haven, Connecticut: 2002.

Ferrer, Elizabeth and Cecilia Puerto. Latin America Women Artists, Kahlo and Look Who Else: A Selective Annotated Bibliography, No. 21, Westport, Connecticut: 1996.

Goldman, Shifra. Dimensions of the Americas: Art and Social Change in Latin America and the United States. Chicago: 1994.

Kaufman, Frederick. Manuel Alvarez Bravo: Photographs and Memories. New York: 1997.

Livingston, Jane. M. Alvarez Bravo. Boston, Massachusetts and the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC: 1978.

Mosquera, Gerardo. Beyond the Fantastic: Contemporary Art Criticism from Latin America. London: 1995.

Oles, Jay, ed. South of the Border: Mexico in the American Imagination 1914–1947. Washington, DC: 1993.

Poniatowska, Elena, Berler, Sandra, Palma, Francisco Reyes.

The Edge of Time: Photographs of Mariana Yampolsky, Austin, Texas: 1998.

Sullivan, Edward (ed.). Latin American Art in the Twentieth Century. New York: 1996.