Ruth Ziv-Ayal

Ruth Ziv-Ayal, a director and choreographer, is one of the most significant figures in Israeli experimental movement theater. She was the first to choreograph in this style, beginning in the first half of the 1970s until 2014. Her early work was characterized by the use of everyday materials such as household tools, newspapers, and balls. Her work during the 1980s and 1990s expanded to use materials such as soil, sand, water, bread, and clothing. Ziv-Ayal choreographed for the Kahan Theater in Jerusalem, Ruth Eshel Dance Theater, Cameri Theater at Tel Aviv, Kibbutz Dance Company, Batsheva Dance Company and in 1982, she set up her Ruth Ziv-Ayal Troupe. She has taught at the Beit Zvi acting school and was a professor at the Theatre department at Tel Aviv University.

Ruth Ziv-Ayal (née Sprung), a director and choreographer, is one of the most significant figures in Israeli movement theater. She was the first to choreograph in this style, beginning in the first half of the 1970s. Her creative output of more than thirty years, which is performed by an experimental theater group or a troupe of actor-dancers that she assembles anew for each project, employs a unique language of movement that she developed during years in theater and in teaching. Of the subjects presented in her work, she says: “How you meet and how you part: these are personal, intimate subjects that affect the soul of every human being … the questions connected to human life and my own life. … What changes as time passes is the medium: sometimes I use balls or newspapers, and sometimes water or sand.” (interview with author)

Family & Training

Ziv-Ayal was born in Haifa on January 4, 1944. In 1933 her father, Zwi (Herman) Sprung, who was born in Berlin in 1913, emigrated to Palestine, where he worked as a locksmith. He died in 1981. His wife, Regina (née Weiss), born in Berlin in 1914, also reached Palestine in 1933; she was trained and worked as a children’s nurse and died in 1999. The couple knew each other from their membership in a Zionist youth movement. On arriving in Palestine they joined a kibbutz and subsequently married. Regina’s family changed its name to the Hebrew name Ziv, a name that Ruth later adopted. In addition to Ruth, the couple had two daughters: Naomi (b. 1939) and Shulamit (b. 1947).

When Ziv-Ayal was eleven years old she began to study modern dance with Naomi Aleskovsky, a soloist in Gertrud Kraus’s company. She took part in several of Aleskovsky’s productions, including The House of Bernarda Alba (1964) and Sun: Ritual Dance and Elusive Visions for the Bimat Mahol troupe (1965). Under Aleskovsky’s tutelage she learned the fundamentals of classical ballet and also the Martha Graham system of modern dance, together with modern dance exercises influenced by the Ausdruckstanz style of expressionist dance. She placed much emphasis on her improvisational studies, in which she excelled. She later studied in the theater department of Tel Aviv University and in 1966 went to New York to study. She stayed there for five and a half years, during which she earned both her bachelor’s (1968) and master’s (1970) degrees in dance at New York University’s School of Performing Arts. The director of the department was Jean Erdman, one of the first dancers in Martha Graham’s company. Richard Schechner, who gave a course on ceremony and ritual, was also on the faculty. This was a period of thriving for theater arts and fringe productions in New York, which included Happenings by Allan Kaprow and experimental theater in the form of works by Richard Schechner, Joseph Chaikin, and Judson Church.

In 1971 Ziv-Ayal returned to Israel. In 1973, she married Avishay Ayal, a painter and lecturer born in 1945. They have two daughters: Alumah (b. 1975) and Nurit (b. 1978).

Teaching & Choreography

Ziv-Ayal’s early work was characterized by the use of everyday materials such as household tools, newspapers, and balls. Her work during the 1980s and 1990s expanded to use materials such as soil, sand, water, bread, and clothing. Most of her work does not use text, the sounds coming rather from the concrete actions or the voice of the actor. Usually a small prepared sound track is used.

Ziv-Ayal’s work develops slowly in order to “give [viewers] time to breathe the moment and come to the full richness of the subject; like a hand-woven carpet, they must discover all the richness of the patterns within it.” (interview with author) She chooses to work with actor-dancers in a protracted process that includes improvisation and defined tasks while giving expression to the performer’s personality. Her works lead the viewer into an imaginative and sensual experience, though they all carry messages that can be decoded in political, psychological, and social contexts. Ziv-Ayal began to teach movement at the Beit Zvi acting school upon her return to Israel in 1971. Since 1978 she has also taught in the theater department at Tel Aviv University. At the same time, she worked as a choreographer at the Khan Theater in Jerusalem, with the artistic director Michael Alfreds. In that setting, she created the movement for The Persian Protocols, Fun-Shun, and The Immigrants. With Alfreds’s encouragement, she created a project for the theater, Secret Places (1976), her first movement theater work in Israel. The performance was a kind of “modern tale” in which a young couple encounters imaginary characters whose style is defined by the personification and humanization of silverware, buttons, bowls, ropes, and keys. The performance contains neither text nor music; the only sounds are those made by the objects as the characters move. Idit Zartal wrote of this unknown genre in Davar, saying that “Secret Places is a most remarkable play in Israel’s theatrical landscape, bringing it a new refreshing breeze that just may test the limits, and expand the horizons of local theater.”

In 1978 Ziv-Ayal choreographed The Scarecrow for a solo performance by Ruth Eshel. Ziv-Ayal made Scarecrow driven by her wish to bring the dancer to a reduction in movement. The scarecrow is stuck in its place with a trashcan instead of a head, and it dreams of walking away and breaking free from its isolation. The round can, like the scarecrow’s clothes, was supposed to cancel frontal presentation and increase the importance of movement to every direction. The scarecrow, planted on its spot, dreams of walking about and being liberated from its solitude as it mutters about dreams, the vocals accompanying the movement being part of the choreography.

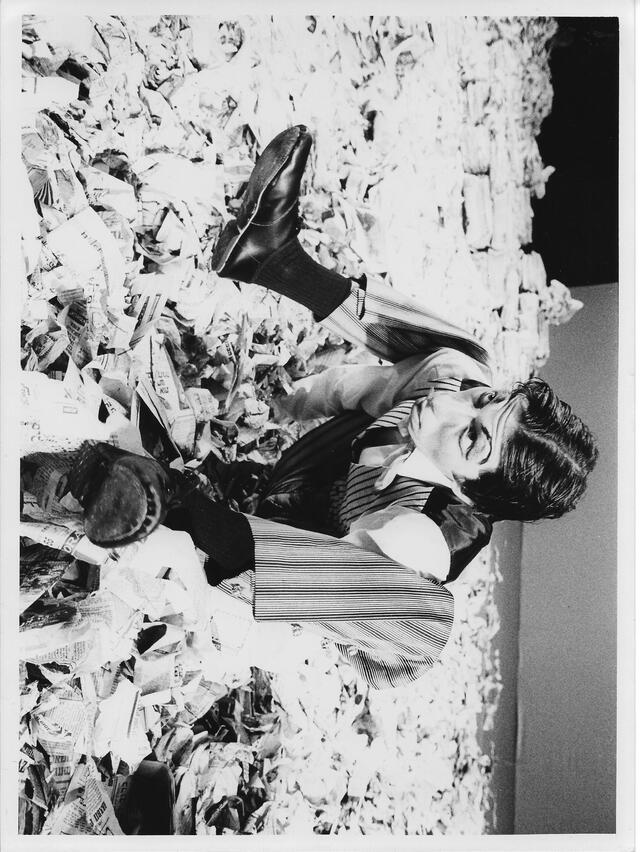

In 1979 Ziv-Ayal created a show for Ensemble II of the Cameri Theater. The performance comprises two parts: Headlines and Bounce Back.” In the former, piles of newspapers are strewn all over the stage, serving as scenery, props, and ingredients for creating the characters. This is a bittersweet, humoristic look at contemporary culture, the power of the media and their transformation of human beings into their servants. Bounce Back depicts a magic playground, an embarrassed character from the nineteenth century, and “vacationers” wearing striped clothing playing with balls of all sizes, from giant beach balls to ping-pong balls.

Yehudit Arnon, director of the Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company, was open to new ideas, and she invited Ruth Ziv-Ayal to create two dances for the company. The first was White Death (1981), at the center of which is a virtuoso solo for a dancer who is always in conflict with the company, a sort of individual against the collective, until the bitter end. The second dance was Koach Meshi’ha (Gravity,1989), commissioned especially for the Israel Festival in Jerusalem. The complex production has three parts: in the first, “Gravity,” the dancers move quickly and bump into each other, pushing and pulling each other. The second part, “The Gatherers,” presents aggressive, dwarf-like creatures who live in the forest and struggle to survive; in the third part, “Orbit,” the dancers, wearing bright orange clothing, stand in place and move slowly and almost imperceptibly. Ayal was accustomed to creative cooperation with dancers who knew and admired her work. Arnon, however, spoke of how difficult it was for her to encounter “rebellious” dancers: “Ziv-Ayal’s Force of Gravity was amazing, unlike anything else. She asked them to walk like washerwomen, and the dancers shrieked that it was impossible. Terrible for the back. They rebelled. … Then I remembered Boaz Cohen. He’d quit the company to dance with the Cullberg Ballet,and had told me once that they had walked like a washerwoman. … and then the dancers yelling ’we can’t’ didn’t scare me.” (interview with author)

In 1981 she set up the first cast of her movement theater group, the Ruth Ziv-Ayal Troupe. At the initiative of Oded Kotler, the group worked at the newly established Neve Zedek theater center (today the Suzanne Dellal Center), where it performed a number of compositions between 1981 and 1998.

Machzor (Cycle,1982), commissioned by the Israel Festival, was performed in the open air, on an earth stage in which was a pool of water. The work, for a cast of twenty, has three parts: the first depicts primitive, violent creatures who roll about on the earth from which they were created; in the second, the company divides into groups of young boys and girls who play courting and power games on the sand and in the water; and the third part depicts monks or nomads in the desert who begin delicately to sing, searching for their way to spirituality. Cycle left a profound impression and was given a great deal of media coverage.

Blai (Wastage,1984) presents a story of escape and survival. Six members of the company leave a closet and pile clothing on the stage. Putting on and taking off layers of clothing, the performers assume roles and change identities. The show was murkily lit, on the border between light and darkness, bringing to mind expressionist horror movies. A heap of clothes and dress accessories piled up at one end of the stage, a kind of mass grave that brought to mind memories of the Holocaust; although Ziv-Ayal chose not to deal with the subject directly, it seems that its images and association snuck into the work.

Halon (The Window,1986) is a macabre family story, inspired by the life cycle of the black widow spider, which devours its mate after mating. In this work Ziv-Ayal took an antithetical stance toward received gender perceptions. The three young women wear shiny dresses, tempting the animals they intend to trap and eat. They resemble wild kittens, uttering growls and cruel cries, and when they begin to jump, like dragons they “spit fire” of colorful paper ribbons. The mother lurks upstage, a kind of crone resembling a bundle of rags (Gaby Aldor) croaking like an ancient cracked tree. A beautiful crystal ball rolls out from between her ugly legs. A man (Hemed Schulberg) enters the arena, a kind of gentle prince, a man-woman hybrid. He is dressed as a woman, to fit in, a transgender element new to the era. Hezy Leskly wrote: “There’s no blood. Rather than spilled entrails there are strips of colored paper. She submerges this cruel violence in a sea of beauty. We have not seen such an esthetically perfect work here for a long time.”

From 1990 to 1994, Ziv-Ayal choreographed Chapters, a continuous theatrical piece in seven sections, for the Suzanne Dellal Dance Center at Neve Zedek. The work depicts a tribe of people who go on a journey. In walking, the human being’s most basic and daily activity, the people reveal their weaknesses and limitations. While each part of Chapters stands on its own, the presentation of several together allowed for a broader and more complex tapestry. Each part was presented to the audience once a month as a separate event, and such a performance was called a “sketch.” Each new part that was created led to change and updating all the earlier ones and these changes were apparent when the parts were presented together in a marathon performance. This manner of performance allowed the audience to be partners in the development of the saga and to grow close to the characters as they appeared over time.

In 1993 Ziv-Ayal created Koach Meshi’ha (Gravity), returning to the subject of death and reincarnation, which followed her during her creative life. Six characters walked and fell, revealing creatures that some time in history began to undergo a process of mummification that was cut off. There is a layer of transparent nylon over their bodies, as if wrapping something for safe keeping over a long period. The embalmed begin to divest themselves of the adhering nylon, tearing at it with their hands and teeth, like a snake that has shed its skin. Then they undergo metamorphosis, a renewal of life, and a kind of inner heat begins to nourish them; the skin warms and glistens, the muscles relax, and the creatures become human. Those who have won new life spread their cloaks on the stage, sit on them, and begin to sing.

Mangrusim (1998) was a solo performance choreographed for the Suzanne Dellal Center and sponsored by the Batsheva Dance Company. It is a homeless woman’s abstract journey among a landscape of stones. She dances on the stones, eats them, sings, feels pain, and laughs with them. The performance has three parts: gathering, a meal, resting. It takes place on stage and the proximity that is created allows viewers to look closely at the minutiae of breathing, movement of the fingers and the shape of the stones.

Ruth Ziv Ayal’s “The Supper of Da’let and Gimel”

The Supper of Da’let and Gimel: homage to Samuel Beckett (2008), is movement-theatre for two performers with Thirteen Words: “Two stop along the way to eat, Place, here. Time, now.” Her last work was Rujum (2014) [A stone heap to mark the road for nomads walking in the desert], a solo for performer Yael Turjeman.

Throughout her career, Ziv-Ayal taught movement for actors at the Bet Zvi Theater Arts school in the theater department of the Arts Faculty at Tel Aviv University, where she is a professor, and at the dance theater department of the dance faculty at Kibbutz College. As her health has deteriorated, she has stopped creating and teaching.

In 1979 Ziv-Ayal received the Silver Rose award of the Ma’ariv daily newspaper for an original creation for the theater, in 1996 Tel Aviv University’s Rosenblum Prize for Theater Arts, and in 2014 the Kipod Hazahav (golden hedgehog), awarded annually for excellence in Fringe theater in Israel.

Arnon, Yehudit. Interview with the author, 19 September 1996

Avigal, Shosh. “Life’s Concentrated Formula.” Davar (9.3.1982).

Aldor, Gaby. “Cycles—A work in progress.” In Israel Dance Annual 1983: 26–29.

Bar-Kadman, Emanuel. “A man’s visit.” Yedi’ot Aharonot (July 25, 1986).

Eshel, Ruth. Dance Spreads its Wings: Israeli Concert Dance 1920-2000. Tel Aviv: IsraelDance-Diaries 2016.

Handelsalz, Michael. “Finally, theater.” Ha’aretz (July 24,1979).

Hashilony-Dolev. “A different dance.” Yedi’ot Aharonot (February 19,1992).

Witz, Shosh. “Relationships form and end.” Yedi’ot Aharonot (March 23, 1984).

Zartal, Idit. “Surprise, humor and the rest of the spirit.” Davar (September 8, 1976).

Yaron, Elyakim. “Experience without words.” Ma’ariv (July 29, 1979).

Yaron, Elyakim. “The clothes are rags.” Ma’ariv (March 9, 1984).

Leskli, Hezi. “Coming out of the closet.” Ha’ir (February 24, 1984).

Leskli, Hezi. “Swallowing life.” Ha’ir (August 8, 1986).

Fuchs, Sarit. “The body cannot lie.” Ma’ariv (June 26, 1979).

Manor, Giora. “The exile of the remembered headline.” Al Ha-Mishmar (June 6, 1976).

Manor, Giora. “Of balls and newspapers.” Al Ha-Mishmar (June 2, 1976).

Manor, Giora. “Water and soil.” Al Ha-Mishmar (September 5, 1982).

Manor, Giora. “A window to women’s realm.” Al Ha-Mishmar (August 9, 1986).

Manor, Giora. “The wondrous journey of Ruth Ziv-Ayal.” Israel Dance Quarterly 4 (October 1994): 10–15.

Reuven, Tikvah. “Dialogue without words.” Yedi’ot Aharonot (July 9, 1979).

Zartal, Idit. “Surprise, Humor and Inspiration,” Davar (September 8, 1976).