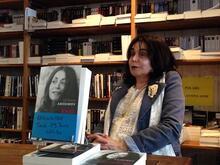

Krystyna Zywulska

Born Sonia Landau in 1918, Krystyna Żywulska escaped the Warsaw Ghetto, hid as a Christian, and helped other Jews in hiding during the Nazi occupation of Poland. She was arrested by the Nazis, imprisoned, and sent to Auschwitz, from where she escaped in 1945. She remained in Poland, and even after the war, she hid her Jewish identity, until she eventually published an autobiographical novel in 1963. She left Poland in 1968 and settled in West Germany, where she died in 1992.

Krystyna Żywulska was born Sonia Landau in Łódź on May 10, 1918. In 1936, she graduated from high school in Łódź and worked as a legal assistant in the offices of defense lawyers. At the turn of 1939 she went to Lviv (Lvov), which was then under Soviet occupation. Returning to Warsaw in 1941, she had to live in the ghetto, from which she escaped with the aid of a gentile woman involved in the Home Army (Armia Krajowa, the Polish underground military organization). Until the spring of 1943 she lived on the “Aryan” side, helping other Jews in hiding. In June 1943 she was arrested by the Germans and imprisoned at the Pawiak prison in Warsaw, from which she was taken to the Birkenau death camp. During the evacuation of the camp in January 1945, she escaped and hid with a Polish family in Silesia.

After the War

After the war she lived first in Łódź, where she worked for the Glos Ludu newspaper (she made her debut there with reviews in 1945), and then moved to Warsaw, where she worked as a journalist (contributing to numerous newspapers and journals, including the popular weeklies Szpilki and Swiat), writer, editor and translator (from Russian into Polish). In 1946 she married Leon Andrzejewski. In the same year she published her war memoirs, Przezylam Oswiecim (I Survived Auschwitz), in which she does not mention her Jewish origin at all and presents herself as a Christian Pole (for example, she mentions receiving parcels and celebrating Christmas), although in several places she expresses sympathy for the plight of Jewish prisoners and victims. In 1963, however, she published another autobiographical novel, Pusta woda (Empty water), which covers an earlier period of her stay in the Warsaw ghetto and in which she speaks from her Jewish point of view. In juxtaposing the two books it is clear that, after surviving the war under a false identity, for a while she did not want to reveal her real self. Apparently, a passage of time was needed for her to do that. Commenting on this unusual situation, Henryk Grynberg stated: “There were many cases of Jews who after the war were afraid to admit their Jewishness, especially after such experiences as those Żywulska lived through. But this is perhaps the only known case in which a writer narrating her profoundest personal experiences and the tragedy of her people in the first person conceals her true identity from her readers. This must be considered yet another of the unprecedented tragedies of the Holocaust” (Grynberg, 41).

Żywulska ends her second life-story with a long and moving list of the people she mentions in the narrative—relatives, friends and casual acquaintances, most of them victims of the Germans—and laconic information about the fates that befell them. In the last sentence she states: “I write. Mainly satirical monologues.” She actually was an author of satirical pieces and cabaret songs as well as of some books for children. She cooperated with the Syrena (Mermaid) Theatre in Warsaw and the Polish Radio.

Life in West Germany

In 1968 Żywulska emigrated to West Germany and in 1970 she was expelled from the Polish Writers’ Union. In the years 1969–1970 a number of writers of Jewish descent were forced to leave Poland as a result of the so called anti-Zionist and in fact antisemitic campaign instigated within the ruling Polish Workers’ Party. Thereafter she was on the censors’ list and could be referred to only in academic publications. In 1992 her first book was re-published by the Auschwitz Museum.

After her death she became the protagonist of a German novel Und die Liebe? frag ich sie (And love? I ask you) written by Liane Dirks and first published in Zurich in 1998. Dirks tells the turbulent story of Żywulska’s life, focusing on the unknown episode from her biography: her passionate love affair with a young German dramatist who came to Warsaw in the 1950s to seek her expertise and love in order to ease his sense of guilt. Żywulska died on August 1, 1992 in Düsseldorf, Germany.

Selected Works

Przezylam Oswiecim (I Survived Auschwitz). Warsaw: Wiedza, 1946.

Pusta woda (Empty Water). Warsaw: Iskry, 1963.

Tu mowi zyczliwy... (Your Friend’s Speaking...). Warsaw: 1954.

Tak zwane zycie (The So-Called Life). Warsaw: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1956

Jasia dziwne pomysly (Jas’s Strange Ideas). Warsaw: Biuro Wydawnicze Ruch, 1966.

Kup mi, mamo (Mommy, Buy Me This). Warsaw: Biuro Wydawnicze Ruch, 1967.

Sen Jasia (Jas’s Dream). Warsaw: Biuro Wydawnicze Ruch, 1967.

Pamietnik lalki (The Doll’s Diary). Warsaw: Biuro Wydawnicze Ruch. 1968.

Grynberg, Henryk. “The Warsaw Ghetto in Polish Literature.” Soviet Jewish Affairs 2 (1983): 33–46.

Levine, Madeline G., “Polish Literature and the Holocaust.” Holocaust Studies Annual: Literature, the Arts, and the Holocaust, edited by Sanford Pinsker and Jack Fischel, vol. 3. Greenwood, Florida: 1985, 189–202.

Wrobel, Jozef. Tematy zydowskie w prozie polskiej 1939–1987 (Jewish Themes in Polish Prose 1939–1987). Krakow: Universitas, 1991.